Reflect on the relationship between artists and subjects and the responsibilities involved in representing communities

Each of these series documents a community through portraits of its members. The works ask us to question the power dynamics between subject and photographer. This display raises questions about the relationship between artists and subjects, the intended audience for these images, and how their meaning might shift depending on the context in which they are seen.

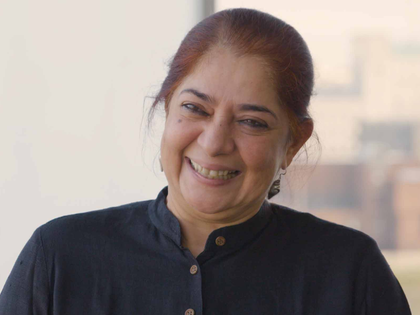

Sheba Chhachhi joined the women’s movement in India in the 1980s. She participated in feminist activism and photographed fellow activists. In the 1990s, she re-evaluated ‘the representation of politics and the politics of representation’. She reshot some portraits, asking each woman to take control of the process.

Like Chhachhi, Claudia Andujar’s attitudes to recording a community shifted over time. In the early 1980s she shot identity photographs of Yanomami people in the Brazilian Amazon region. This was part of a vaccination campaign she led. Looking back on these images in the 2000s, Andujar decided to make a work that ‘questioned the method of labelling people for whatever ends’.

Over four years, Paz Errazuriz recorded the daily lives of members of a community of cross-dresser and transgender sex workers in Santiago, Chile. The photographs were taken during the military dictatorship (1973–1990). Its authoritarian rule threatened LGBTQ+ people’s freedom and safety. Errazuriz’s photographs, and the participation of her subjects, were acts of political resistance.

Susan Meiselas’s 20 Dirhams or 1 Photo? 2014 was made during an artist’s residency in Morocco. Meiselas worked collaboratively with women she met in Marrakech to explore the ownership of their own images.

Tate Modern