Imagine this scenario: you are locked in an empty white room. You share this cell with twelve other people, but you are not allowed to speak. You are under constant observation. Are you taking part in a Beckett play, or are you a prisoner in a panopticon?

No, it is the first day of the 1969 autumn term in the Undergraduate Degree Sculpture School at what was then St Martin’s School of Art. The students, including Richard Deacon and Tony Hill, were locked in a studio every day for eight hours for a term. They were not allowed to leave the room, and remained under the staff’s constant surveillance. Each student was given one particular material – it might be a block of polystyrene, or a bag of plaster. With this they had to work for an unspecified period of time, with no critical feedback from their tutors.

The programme, known familiarly as The Locked Room, represented one of the most radical episodes in British art education. The students began their academic careers with an attempt to erase tradition, art history and even, at times, their own work. Under the direction of tutors Peter Kardia, Garth Evans, Gareth Jones and Peter Harvey, The Locked Room was a prescient response to the emerging conceptualisation of art practice in a post-1968 world. The students were, essentially, starting from scratch. Such a tabula rasa was intended to provide an alternative to traditional teaching methods. As Kardia said: “I wanted to put them in an experiential situation where they couldn’t grasp what they were doing. What I wanted was ‘existence before essence’.”

The preceding generation of St Martin’s students, including Richard Long and Gilbert & George (who had themselves rejected Anthony Caro’s sculptural teaching aims), hadn’t just reduced their dependence upon the sculptural object; they had done away with “matter” altogether. Such a removal raised a sticky question for art educators: how do you teach something that has no defined subject or medium, process or protocol?

Kardia established a pedagogy based on paradox: literally imprisoning students in order to liberate them. Garth Evans emphasised the importance of these negating practices: “If one is not careful as an art teacher, one can believe that one has the obligation to tell a student what to do. What I learned in The Locked Room is that all one can intelligently tell a student is what not to do.”

The term’s close saw a fitting conclusion to a course designed to liberate its participants. The students were outraged that the course’s goal of “subversion” was sidelined to fulfil bureaucratic requirements, so they addressed these requirements with a suitable response. For example, Richard Deacon, Ian Kirkwood and Ted Walters installed a chicken coop in the studio, arguing that its occupants could perform the same functions as themselves.

The programme demonstrated Kardia’s conviction that the greatest danger to artistic endeavour is habitual practice. They were trained to see with un-habitual eyes – a perspective that would prompt them to re-conceive traditional materials as they arrived at a fresh understanding of their media. Thirty-seven years on, the occupants of The Locked Room still deliberate over the value of their unconventional student years.

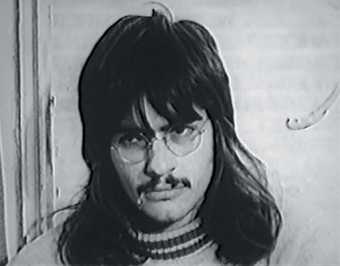

Richard Deacon, sculptor

One of the really radical things about the programme was that it showed close attention and regard [to the students] and valued what it was you were doing without evaluating it, for better or worse. There were times when you made attempts to undermine the system in a slightly schoolboyish way, but, finally, it was to do with selfcriticism rather than institutional evaluations. It was very important that we trusted absolutely that there would always be someone there, and our tutors sustained total commitment to being there, everyday.

Student drafted in for reconstruction

© Photograph: Garth Evans

Tony Hill, filmmaker

I found the authoritarian nature of the project rather oppressive. It was a prison, where action was taken out of boredom as much as anything else. We entered the room to find a cube-shaped parcel with our name on. It was a cube of expanded polystyrene, and I spent time burning holes through it with cheap Spanish wax paper matches. I can’t remember what the others did, except that Andrzej Klimowski did nothing with any of the materials.

Tim Jones, artist

This course set things up that have affected me ever since. It took a radical position. The position of the staff was ‘we do not assume what art is’, and how you interpreted that was up to you. There was no sense that we should follow a linear trajectory in sculpture, but the implication was that borders could be broken down. I remember the endless handling of materials, working with things of no material value, with no tangible evidence of production. The immaterial quality of our work is commonplace now, but it wasn’t then. I still refer to this time in my own teaching today.

Ian Kirkwood, painter, head of fine and applied art at De Montfort University

On the very first day I remember being shocked, intrigued and puzzled as I stared at the block of polystyrene wrapped in its brown paper, thinking frantically, trying to work it all out. The invitation was there, in the material, what was I going to do with it? One of the key memories I have is realising very early on that we were not being provided with models of what to do; that the expectations of staff as determinants of what or how to make work had been taken away. This was both liberating and alarming. Until that point I had not appreciated the role that the expectations of others had played. It undoubtedly forged many of us as artists and teachers without handing out a prescription.

Deirdre McArdle, sculptor

Everyone could see the sense in The Locked Room idea (apart from one or two who dropped out). In a way, it was a charming game for Peter and his staff. Although we could baulk at its discipline and intensity, we could see how it helped our attention to focus, and I think we were flattered by the atmosphere of seriousness.

The Locked Room Project

Day five: burning polystyrene in the background

© Photograph: Garth Evans

David Millidge, businessman

When I entered The Locked Room my life changed direction. I was young, naïve, non-academic, but hard-working and adaptable. I had been thrust into the world of ‘concept art’, and this experiment certainly did awaken me to a wider spectrum of possibilities. I am sure that the course was partly responsible in forging the personality that has guided me through the past 37 years. However, as my portfolio included no sculpture in the conventional sense, my post-graduate applications were unsuccessful, and I became a shoe salesman at Romford market. I was very successful and now run my own import company, importing shoes from Brazil and selling to all the high street chains. Looking back now, The Locked Room gave me a great education in life, but I feel sad to think of all those fantastic, sensual, provocative, real sculptures that I never made.

Greg Powlesland, sculptor

When I applied to St Martin’s, I didn’t realise that the course was going to differ so greatly from my first impressions of the sculpture department. It was a shock when I arrived. There were interesting aspects to the course, and, in many ways, what we regard as contemporary art practice today seemed to stem from it. The tutors certainly had a clear plan, but I felt the programme lacked subtlety and sensitivity. Its value was questionable. I was, and still am, more interested in traditional aspects of sculpture, so I drifted away from this course and moved down to the welding basement.