VIJA CELMINS: When I was a student we were all interested in Abstract Expressionism. We wanted to do big, great paintings. However, later on, when I was living on the West Coast, I dropped it and started making paintings that were based on what I could see. I tried to forget what was in my mind; I had been thinking too much about the work and inventing too much, and it seemed to mean nothing. So I thought I would try to get to some other place that was a little more primitive, maybe more old-fashioned, without really thinking. I was trying to find a touch that was mine and not that of some other famous artist such as de Kooning or Gorky, both of whom I admire. I painted everything in my studio – spoons, forks, my food, cups, a lamp, the toaster.

SIMON GRANT: Why just things in your studio? What about outside? Because Venice Beach, where you were living at the time, is a nice place, isn’t it?

VIJA CELMINS: Yes, but artists in Los Angeles didn’t sit outside in the smog on the freeway, painting. I did drive around at the beginning and try to do landscape – not really from looking, but more from what I knew about how a painting should look. I was not used to looking outside the painting itself and the studio. I wanted to be an abstract artist really, but to revitalise my work I started painting the things around me instead.

SIMON GRANT: I’m curious why you chose the indoor objects, because a lot of other West Coast artists, such as James Turrell, were interested in the light.

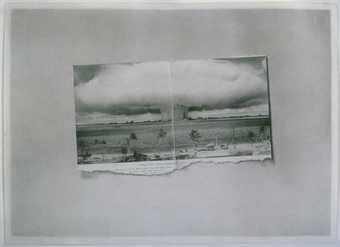

VIJA CELMINS: Well, I got interested in light a little bit later when I became more sensitive to the landscape of the West. However, I was basically a painter with the baggage of brushes and turpentine, paint tubes and a two-dimensional support. My return to still-life was inspired by a desire to look outside my head to paint what I could see. There were so many artists working with objects in the early 1960s – Warhol, Oldenburg, Johns, and Morley with his photographs. I also liked Morandi’s fascination with objects, and I remember the shock in his work of finding something so small and modest, but yet having such a powerful presence. I looked at Magritte’s paintings also. I started going through my photographs and newspaper clippings that I had collected – images of Second World War planes, a nuclear explosion at Bikini Atoll, an airship – and I made drawings of those.

SIMON GRANT: Were they intended as memory pictures?

VIJA CELMINS: Maybe anxious memories, I guess. Memories from my childhood in Latvia and Germany. These were partly autobiographical works. I think I was reliving and thinking about who I was, maybe, and the images that were in my head. Also, the Vietnam War was going on, which at the time I was crazed about.

SIMON GRANT: Yes. You took part, along with Donald Judd, Eva Hesse and James Rosenquist, in the mass demonstration, the Artists Tower of Protest, that was put up along La Cienaga Boulevard in Los Angeles in 1966.

VIJA CELMINS: I did march and yell and protest. And some violent images did come up in my work.

SIMON GRANT: At first glance they seem photorealistic, but.

VIJA CELMINS: Well, I found the work of the photorealists a bit dead, but I got interested in the photograph. I used the photograph as a guide, so I would not have to worry about the image. They are images within an image within an image – drawings of two-dimensional images. I was trying to bring the images back to life by putting them in a real space that you confront. I don’t think anyone else was making work like this at the time, not clippings of disastrous events. Now they look a bit ridiculous to me.

SIMON GRANT: Why ridiculous?

VIJA CELMINS: They look almost too contrived. Of course, I didn’t really think like that at the time. I remember thinking that the making of the image was reason enough to do it. It was about finding a touch; a way that the image could sit on the surface. The whole point for me was that even though art has been through a million things, I wanted to get in touch with something more primitive than my wandering and skipping brain.

SIMON GRANT: In this period you chose what seem like male subjects – airplanes, a gun, a nuclear test explosion.

VIJA CELMINS: I think I felt that these images belonged to all of us. they were our images. However, I must have been interested in Freudian, phallic imagery of some sort, right? There is a photograph of me taken in 1966. I had been working on a large sculpture of a pencil stub, which is sitting beside me, along with a nude mannequin that someone had brought over for me to decorate for a show. that photo would have inspired Freud! I think many young artists have sex on their minds, and I think I did too. The drawing of the gun [Clipping with Pistol 1968] came from the fact that a friend of mine had been attacked and her boyfriend gave her a gun, so I wanted to do a picture of it. I did some paintings, and then got interested in gun magazines, tore out some clippings, did this one drawing and then lost interest.

SIMON GRANT: You did paintings, but then you decided to stop, and to concentrate on making drawings. What happened?

VIJA CELMINS: I raced through many object paintings, being unsatisfied with the conventional space they had. Then I had a realisation that the image and the support should unify, and the way to do it was with a pencil. I thought the precise point would be a better and clearer recorder of my touch. So I went ahead making all of my art with a pencil. It was stupid, in a way, because the drawing took me out of a richer life in painting for some fifteen years. At any rate, I started drawing the photographs and clippings I had collected. I loved the images brought back from space, which were showing up in magazines, and I myself had been taking photos of the ocean in Venice. I had been thinking of making a film about the surface of the sea, and had been inspecting it through the camera. I did make several short films, one of my light bulb, which hung above my table in the studio. That one, I still have. But mostly I was deadly serious about the drawings, as you might be able to tell by looking at them.

SIMON GRANT: So, in fact, you were actually interested in light, as well as doing things in your studio?

VIJA CELMINS: I think I’ve always been interested in light. It is what makes the images. The dark graphite and the light of the paper unfold together. I made them in a deadpan way – and spoke of them as having “no composition/no gestures/no artificial colour/no distortion/no angst or effort showing/no ego/deadpan paintings. I know nothing, I compose nothing”. Sort of silly, thinking about it now. Though I remember at the time that I had this feeling that no matter what I did, just to present the facts, there was still something in the work that was mine, that came through the making. Later, maybe twenty years later, I thought I had found some kind of touch, not really a stroke, but a touch, but now I believe it is more like a sensibility that you present. What do you think?

SIMON GRANT: I think it’s a tone. There is a mixture of restraint and a feeling of the energy that’s gone into making them.

VIJA CELMINS: I think the restraint comes, maybe, from my own nature, from wanting to hold something back in the work, and from the fact that I had rejected so many things. I had rejected gesture and composing obviously, I’m composing, but in a very toned down way. I’d given up colour. I’d given up a big size, which we all wanted so badly. I’d made some very big things before I dropped the scale down. I’d been very inspired by Ad Reinhardt’s 1953 essay Twelve Rules for a New Academy, in which he saw a new way for painting, based primarily on negation and reduction. It was beautiful writing from a frustrated but intelligent man trying to find in words what art might be. I think I took much of it to heart, and I thought: “What is me?” So I threw away a lot of the stuff that naturally went into painting. I wanted to make it lean. I did a talk with Chuck Close in a book for Art Press, in which we discuss our relationship with using a recognisable image in our work. He is really involved in systems of perception. me too. Though my work is more varied. As you can see, the work gets a little flatter as time goes by. For instance, in the later ocean work from 1977, the image lies close to the paper, and describes the surface of that paper as much as anything.

SIMON GRANT: What’s the difference between the earlier ocean works and the later ones?

VIJA CELMINS: The earlier work has these big Baroque dark “holes” in the waves. The waves are more like objects and make a more animated, pictorial space. The later work is a larger view, but made with smaller waves, more even and regular, with the tone of the pencil kept in check. The image is more flat with a slight indication of perspective.

SIMON GRANT: Why did you keep repeating the image of the sea?

VIJA CELMINS: I thought that if everything were stable, what would come out more was the differences in pencil, and the very subtle differences in my mood and in my handling of space.

SIMON GRANT: So, in your own head, you had always intended to see them as a group?

VIJA CLEMINS: Yes. I think if you can stand to look so hard, you will see many repetitions and series from one room to the next. In the work of the 1960s and 1970s, the image is concentrated and projects out into the room, inviting you in and pushing you away. In the later dark night series and webs, the work comes into view only when you are close to it. it invites an intimate inspection. You see what a player the charcoal itself is. In the earlier work, the image itself, and not how it is made, is stronger and these drawings work best at a distance. I like to think that part of my interest in how a work projects came about from spending a lot of time in the desert, where space is often shifting and appears flat at certain times, and is very illusionary. In the late 1960s I used to hang out with Doug Wheeler, Jim Turrell and Tony Berlant. None of them was a painter, but we all loved the desert. At first, you don’t see much, but after spending some time, your perception sharpens, space shifts and changes, and there is this incredible gorgeous light. There is light, of course, in all this work. Maybe in the galaxies it shows up more?

SIMON GRANT: It’s definitely a different feeling. You get a very good sense of intimacy with the desert and ocean works. The galaxy works are more intensely made.

VIJA CELMINS: The material, charcoal and pencil and paper are bigger players in the night sky pieces. The work is much more abstract, and even though your mind says this is a deeper space, I think the uniform nature of the graphite sitting on that surface keeps you engaged in the flat plane. There really is no depth to it.

SIMON GRANT: How are the pencil marks actually made?

VIJA CELMINS: The graphite is just laid on bit by bit, as dense as it can go. The white spaces – the stars – are patches of the paper that have been left blank; I have drawn around them.

SIMON GRANT: Some of the pencil marks are so thickly laid on, it almost looks like paint.

VIJA CELMINS: Yes. Star Field III 1983 took about a year to do. This is a terrific drawing, though I thought I would go crazy if I did another. I did do three, then I stopped drawing totally. As you can tell, even though I try to keep my brain out of things, I’m always beating up the work with a relentless criticising of it. I went back to painting, and did a series of paintings that looked very much like this drawing – dense, layered, very physical. I used to say they looked like a rubber tyre or Formica, they’re so closed off and over-finished. I didn’t get back to drawing for about ten years, until around 1994.

SIMON GRANT: Did your approach to the work change?

VIJA CELMINS: Yes. I started to use charcoal dust to make some pictures, and I started using an eraser, which I never used before. Some – such as Untitled no. 14 1997 – are done with an electric eraser along with other erasers, which is why there is a slightly mechanical quality of recording the stars. I got so crazy working on these, so I relieved this by doing the very corny image of cobwebs.

SIMON GRANT: Why cobwebs?

VIJA CELMINS: Well, first, I found some scientific images of webs at the natural history museum. Very exciting. I thought these webs described the space I always wanted to describe – a surface that has small facets that rigorously account for and record every intersection; a lived on surface. Also, it was an emotional image that would draw people in, so the carefully accounted for space was contrasted with an emotional melancholic image. You know, I like that combination of contrasts - a sort of double reality.

SIMON GRANT: You use the word emotional. Many also describe your work as beautiful.

VIJA CELMINS: Well, you can never really go to beauty like that in your work. I never think of it; sometimes it comes later. I like to think that I neutralise and re-describe an image, and pin it into its new space.

SIMON GRANT: However, it is by your hand; it’s been mediated through your touch.

VIJA CELMINS: Yes, through my sensibility. It’s also a record of a relationship that I’ve had with a set of materials, the making. I try to make the work in a way that has some integrity. I want the flatness to be really real. The image, of course, is not real – it is not the ocean, or a spider’s web, or anything. I want the image to find a relationship with the other reality of the plane. It is integrity in a thought-out way, so that you can accept both of them at the same time.

SIMON GRANT: How is it, seeing more than 40 years worth of drawings together after such a long time?

VIJA CELMINS: Some of it I like, other parts not. There is a feeling of surprise and a bit of wonder. I am a bit detached from it. I see some things that I would not ever do again -like that kind of quality where I tend to close up an image and not let you in, making it too concrete. They almost seem like sculpture. I think to myself, couldn’t I get a little more air into the pictures? When you look at them, don’t you want to come up for breath?

SIMON GRANT: That tension and intensity is one of the good aspects.

VIJA CELMINS: It seems like this show is a real eye test. with so many things going on. I’ve done my part, obsessive as it is. People looking at it have to take it someplace else, they can make the work live.