Richard Shelton on Vija Celmins’s Ocean 1975

There is something about gazing out to sea that awakens deep-seated emotions, even for those of us for whom it is a workplace. Could the explanation lie buried in our unconscious prehistory? Sir Alister Hardy, doyen of twentieth-century marine biologists, certainly thought so. He speculated that our upright posture, relative hairlessness and fat distribution spoke of a longshore phase in the later stages of hominid evolution, a time perhaps when the more resourceful of the children of the savannah realised that the world beneath the waves offered rich pickings for those with the courage and wit to seek them. Just how long it took for our distant ancestors to progress from the gathering of shellfish and easily trapped fishes to the pursuit of more active quarry from vessels bobbing and plunging on the surface of the open sea, we will probably never know. What we can be sure of is that the successive waves of emigration from mankind’s African calf country, which would one day seed the innocent world with people – a process that began more than a million years ago – could not have taken place without the use of boats or rafts.

For almost all of that time man was but a minor player among the top predators of the sea. Like the sea mammals and large fishes at whose lavishly furnished table he was privileged to sit, his power to deplete the populations of his marine prey was easily accommodated by compensatory responses in their rates of growth, reproduction and mortality. However, this desirable state of affairs hid an important difference between the ways in which the long-established marine predators exploited their prey and those of the terrestrial newcomer. Put simply, the reproductive rate of a predator which has evolved alongside its prey is linked to the latter’s abundance. When food is scarce, maturation is delayed, fewer young are born and fewer survive. Were this simple feedback mechanism not built into the reproductive dynamics of the predator by the ruthless forces of natural selection, it would rapidly become extinct. The numbers of predators are thereby held within safe limits by those of their prey. No such safeguard was built into the catching power of the land-based hunter, but so long as his numbers remained low and his fishing methods artisanal, no real harm was done. Greater numbers came with the agricultural revolution, and greater fishing power with the industrial one. For a time the sea’s bounty withstood the efforts of the coal and oil-fired predators to deplete it. It was not to last, however, as first the stocks of shoaling mid-water species such as herring and anchoveta and later the bottom-living white fishes such as hake, redfish and cod showed unmistakable signs of reproductive failure. Finally, feedback reasserted itself, only this time the mechanism was economic. Fishing boats are able to sustain themselves at sea and fish processors on shore for only as long as the values of catches exceed those of costs. Because the unit value of fish tends to increase with scarcity, fishing can remain viable for some time after the point of biological danger has been reached. Eventually, however, the depleted prey exerts its ancient right of control, boats are laid up, processing plants close and ignorant politicians wring their hands. The tragedy is that the means to avoid such unnecessary catastrophes have been known to fishery scientists for more than half a century. Since that time, technical innovation has increased fishing pressure enormously and yet more methods of ecological asset-stripping have been devised, none more repellent than the use of explosives and poisons to exploit the fish fauna of coral reefs already threatened by rises in sea temperature.

Amidst all of this gloom there are limited grounds for hope. For instance, Iceland is now reaping the benefits of matching the catching power of its fleet to the capacity of the local stocks to sustain it, and the artisanal trap fishermen of many nations are achieving the same happy result by informal local agreement. Even stocks of Atlantic salmon, long threatened by interception and global climate change, are growing thanks to the restriction of their exploitation to their rivers of origin. Three small, imperfect steps in the right direction perhaps, but all are examples of the benefits to be gained by respecting the forgiveness built into all living resources. Not until we have spread such good news and applied its lessons across the oceans of the world will we be able again to gaze out to sea with a clear conscience.

Ocean was purchased with assistance from the American Fund for the Tate Gallery, courtesy of the Judith Rothschild Foundation, in 1999.

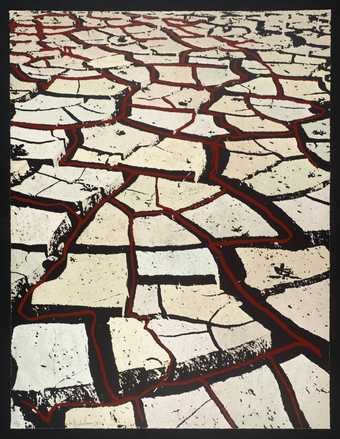

Dai Qing on Menashe Kadishman’s Cracked Earth 1973–4

Menashe Kadishman

Cracked Earth (1973–4)

Tate

Colourful flags and banners were fluttering, and the noise from Haidian Park grew louder and louder. It was 8 August 2006, and an exuberant crowd had gathered near my home on the outskirts of Beijing to celebrate the day, just two years away, when the 2008 Summer Olympics will open with even greater fanfare. But the excited citizens throwing themselves into the recent festivities with great joy and enthusiasm were perhaps unaware that green spaces such as Haidian Park, which function as the lungs of the city, have been shrinking in China’s capital at a truly alarming rate.

Haidian is no longer the park it was just twenty years ago, when I first moved here. Before it was created, paddy fields growing the soft, fragrant West Beijing rice were everywhere. Large ponds with lotus flowers were dotted here and there, and it was easy to buy lotus pods and roots along the roads. A century ago members of the imperial family (and later top communist party leaders) amused themselves in Haidian. They killed time in imperial gardens such as Yiheyuan (the Summer Palace), Yuanmingyuan (the old Summer Palace) and Yuquan shan (Jade Spring Mountain). Cixi, the empress dowager of the late Qing Dynasty, enjoyed spending her leisure hours there floating around by boat. Haidian would also be unrecognisable to the Yuan Dynasty emperors of 300 years ago, when the whole area was a wetland linked to several rivers that provided moisture for the ancient city and its surrounding hills and valleys.

Now the wetland is completely gone, along with the paddy fields and lotus ponds, which dried up as the surface water and then the shallow groundwater disappeared. When the Olympics open in 2008, the ordinary people of Beijing will have to drink water drawn from the Yangtze River, thousands of kilometres away. Meanwhile, the beloved leaders and their families, and others with power and wealth, have already started enjoying water taken from the deep aquifers, where it had been stored for millions of years.

The people singing and dancing in Haidian Park turned a blind eye to the horribly stinking, severely polluted stream that flows through the grounds of China’s two top universities, Beijing and Qinghua. And they paid no attention to the nearby golf course, where precious water is pumped up and poured on to the grass. They may also have been unaware that the water beneath their city has been in serious decline for years, with a huge dry funnel developing underneath 60 per cent of the north China plain, affecting a large area including Beijing and Tianjin and the provinces of Hebei and Shandong. In rural areas of north-west China, which were once covered in forests and where big rivers still flow, women are suffering high rates of infertility because of the shortage of clean water.

But thanks to the Olympic Games and the south-north water diversion project, the folks in the capital can take it easy, and dance around with their silk banners as they practise saying in English: “Welcome to Beijing, our friends from abroad!”

Cracked Earth was presented by Rose and Chris Prater through the Institute of Contemporary Prints in 1975.

Mike Hulme on John Constable’s Cloud Study 1822

John Constable

Cloud Study (1822)

Tate

To John Constable, clouds were the essential frame for his studies of landscape, the standard of scale against which his compositions were structured. Yet for meteorologists, clouds are the most ephemeral of weather phenomena, the hardest to measure objectively and the most difficult to understand in terms of processes of formation and decay. The classification of clouds, following the pioneering nineteenth-century work of Luke Howard, is today still as much an art as it is a science. And they continue to hold a fascination for the general public, as seen in the popular book The Cloudspotter’s Guide, which provides a grand worldwide survey of their history, science and culture.

While clouds played a crucial artistic role for Constable, for scientists trying to understand the way the world’s climate system works, they are the most frustrating and intractable of elements to tackle. They best embody the tentativeness of our predictions of future climate. For example, one the most powerful computers in the world – the 35-teraflop Japanese Earth Simulator (capable of making 35 trillion individual calculations per second) – is still unable to simulate the growth and decay of individual clouds, reverting to statistical approximations of “typical cloudiness” over parcels of sky several square kilometres in size. And the full resources of the CERN Laboratory near Geneva – the particle physicist’s holy city - are to be deployed next year in a series of experiments to discover whether cosmic rays from the sun can influence cloud formation, and hence help to regulate world temperature.

Clouds, then, remain one of the most persistent sources of the uncertainty that afflicts scientists’ predictions of future climate change, an uncertainty often cited by conservative voices in our society as a reason why no urgent action need be taken. Yet climate change is now far more than a discovery of the natural sciences and can no longer be defined, debated and defused through advances in scientific knowledge. Climate change is (as are clouds) as much a cultural phenomenon as a physical reality. Debates about the problem still defer to the authority of the meteorologists and the Earth system modellers, who argue that this tipping point or that climate impact will provide the final piece of evidence to ensure a breakthrough in the international diplomatic negotiations. Instead, underneath the surface, these negotiations reveal the full complexity, inequality and intractability of a troubled world - a world where different ideologies, cultures, faiths and economics battle for ascendancy and power.

We disagree about climate change and what to do about it not because the science is still emergent, uncertain or incomplete. It is not because of the ephemeral and intractable nature of clouds. We disagree because everyone has a stake in the problems raised, and in the solutions offered. To reconcile these different and often competing stakes we need to harness the full array of human sciences, artistic endeavours and civic and political pursuits to make progress – burdening science alone with the responsibility will not make for good science, nor for good policy.

Climate change is not a problem waiting for a solution. Engineers are very useful people, but they are not going to give us the answer here. And climate science will never deliver the certainty about future trends nor unambiguously define the probabilities of climate-related risks which will provide the world with the necessary toolkit to decide what to do.We need a far richer array of intellectual traditions and methods to help to analyse and understand the problem – behavioural psychologists, sociologists, faith leaders, technology analysts, artists, political scientists, to name a few. And we ultimately must recognise that this is the most deeply geopolitical, not simply environmental, issue faced by humanity. It will not be solved by science. Yet climate change can be reconciled with our human and social evolution, with our endurance on this planet, if we allow it to escape from its scientific ghetto. In this sense, it can be defused from being a looming threat to mankind, and instead can be used as a creative stimulus for a more sustainable pattern of life.

The emotive power of clouds, our fascination with them and their scientific intractability make them a good metaphor for the deep complexity of the climate change conundrum. And without clouds, there is no rain, and without rain, we die.

Cloud Study was presented anonymously in 1952.

Paulo Barreto on Henry Rushbury’s The Forest of Brotonne 1920

Sir Henry Rushbury

The Forest of Brotonne (1920)

Tate

The dead tree stump is part of land that has been deforested in Brotonne, France. The painting, done in 1920, is like an announcement of what would start at the end of that decade – extensive deforestation. In 1929 Andreas Stihl introduced the mass-produced, portable, petrol-powered chainsaw. Huge areas of forest could be cleared quickly. In Brazil, this allowed for a dramatic boost in food production. As a consequence, the human population increased, more got access to comfortable housing, their health improved. Not surprisingly, there are those in the forest frontiers of the world who see deforestation as a good thing.

Most environmentalists oppose the process because they know what happens. It is often followed by inadequate land use practices, which, in turn, lead to soil erosion, flooding and ultimately a loss in agricultural production – the very reason for clearing the area in the first place. It is a vicious circle. Extensive deforestation also threatens forest-dependent species, especially in tropical regions rich in biodiversity. The numbers are hard to imagine. Annual deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon consumes about 0.5 per cent of forest cover and has accounted for the destruction of a total of about seventeen per cent of the nation’s forests. The practice is concentrated along major transportation corridors (mostly highways), so the species limited to these regions - some of which we don’t even know – perish. In 2004 the Brazilian Amazon lost about 26,000 km2 of forest cover. Scientists have estimated that this area was home for about 1.3 billion trees, approximately 50 million fowl and almost 1.5 million primates.

However, the major concern is the contribution to global warming. After the forests are cut down, the farmers burn the debris to clear the soil for planting. Burning releases an immense amount of gases to the atmosphere: in 1994 about 75 per cent of Brazil’s greenhouse gas emissions originated from land use.

Deforestation alone is not to blame for global warming, and since it is difficult to hold individuals accountable, the temptation is to ignore the problem in the hope that the practice will decline. Unfortunately, this is unlikely to happen. In recent years it has increased, even though agricultural efficiency for the big money export products (in particular, soya, beef, chicken, sugar, coffee and ethanol) has improved.

One solution is to start living more frugally. Developing nations should not copy the unsustainable model of the developed world. But how to persuade those who wish to enjoy the apparent benefits of economic and social progress? There needs to be a sense of collective responsibility to this problem. And we should remember that every piece of waste means the unnecessary destruction of our land and the homes of wonderful creatures such as parrots, monkeys and jaguars – all part of our global environment.

The Forest of Brotonne was purchased in 1920.