Sam Taylor-Wood

Still Life 2001

Film still

Tacita Dean’s moving film Presentation Sisters 2005, which portrays the quiet daily rituals of elderly nuns living in the South Presentation Convent in Cork, Ireland, unfolds gradually, tracing a gentle slowness. Their routine comprises communal meals, domestic labour, recreation and devotional prayer, each of which Dean spent months observing. One shot shows a nun ironing sheets, pressing out wrinkles with a determined focus and concentrated thoroughness unknown in the frenetic modern world outside. Used to our culture of light-speed pace and miniscule attention spans, multi-tasked distraction and attention-deficit disorders, one discovers an oasis of clarity in the darkened environment where Dean’s film plays. Capturing the unhurried cyclical time of Catholic spirituality, the piece emphasises the sense of prolonged duration through its anamorphic widescreen format, which widens the 16 mm colour film’s image. Time stretches out.

The hour-long work ends with shots of the setting sun, suggesting that religious life is approaching its historical conclusion, absent of a new generation to invigorate its tradition. Dean’s documentary reveals one motivation behind the art of suspended time: to record forms of life that obey temporal patterns which are becoming extinct. Soon, it appears, everything will beat to the tempo of modern capitalism. By re-creating the experience of suspended time, she shows that it allows for a deepened experience of life, lived, in the case of the nuns, to the point of spiritual intensity. Her film also dramatises the fact that the experience of time is far from uniform. Clock time differs from lived duration; historical and cultural conditions – such as living in a convent – affect the perception of time, which has long occupied artistic practice.

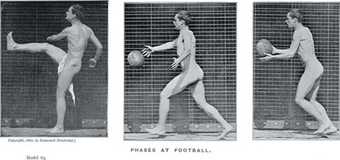

Eadweard Muybridge

Phases at Football (Model 63)

from his book The Human Figure in Motion 1887

The ability to play with time, to postpone it, to quicken it, is a distinctly modern phenomenon.While the concepts of infinity, the eternal, time’s purgatorial suspension, or its termination within narratives about man’s ultimate destiny – the end of the world – were certainly important to past cultures, a change occurred in the West with the Enlightenment. Broadly speaking, an emerging secular humanism introduced ideas of mathematical time, explored its philosophical structure and conceived the relativity of temporal experience outside of divinely orchestrated progression. Modern psychology soon recognised that human beings may experience time’s flow variably; that the lived sensation of duration may be manipulated. The first major rupture with traditional understandings of time occurred within visual culture arguably with the mid-nineteenth century advent of photography, which fascinated precisely because it appeared able to rescue visual appearance from the ravages of time.

The history of photography reveals a further motivation behind art’s experiments in stopping time: to escape death, to reel the body back from certain deterioration. The early Daguerreotype portraits, for example, preserved the body’s image in its best state – forever. The irony is that in severing its subjects from time’s progression, projecting them outside the process of life, photography encouraged a morbid fascination with death, familiar in the allure of the portrait whose sitter has long passed away. Not surprisingly, early practitioners were drawn to Paris’s catacombs. Think of those remarkable shots by Nadar of femurs and skulls assembled into decorative compositions, where the camera captured what it alone could prevent – the transformation of the body into a pile of bones. By conquering time, the photograph creates the non-living, exemplified where the portrait and death join to uncanny effect in the once popular tradition of post-mortem photography of children. As signs of acute grief that denied loss, those images positioned the body between life and death.

R.J. Fittell

Post-mortem photograph c.1890

Albumen print

11.2 x 17.1 cm

© Courtesy Paul Frecker

With recent technological advances, representation appears to gain even greater control over temporal progression. Through the use of time-lapse digital video, Sam Taylor-Wood’s Still Life 2001 shows a Caravaggesque display of fruit, which soon transforms before our eyes into a collapsed mass of rotting matter, the food of flies. Presented in a loop, the passage projects an endless repetition, where death and resurrection acquires endless appeal. Despite the technological innovations, the game is an old one.

Modern art has responded also to the mechanisation of time within modern life. As nineteenth-century optical science grew in sophistication, it brought greater attention to human perceptual capacity. Extending the efficiency and endurance of the human eye was of critical interest to applications within the scientific management of labour, aiming to produce ever stronger and longer lasting factory workers. Artists began to conceptualise the human body as a machine, notably in Marcel Duchamp’s and Francis Picabia’s so-called mechanomorphs. Duchamp’s To Be Looked at (from the Other Side of the Glass) with One Eye, Close To, for Almost an Hour 1918 introduced standardised duration (one hour) into its own viewing conditions. The piece’s title humorously mimics the regimentation of perception, as seen similarly in nineteenth-century chronophotography, where the carefully studied movements of the body were subjected to precise measurements, stopping time incrementally.

Dada and Surrealism suspended time to parody industrialised experience with absurd and zany man-machine hybrids and to escape the tyranny of consciousness by redirecting film into the shocking and surprising, re-creating the supposed temporal conditions of dreams. For Freud, unofficial mentor to Surrealism’s leader André Breton, the unconscious was marked by condensations and displacements that mixed past, present and future. The montage-jumbled temporalities of Surrealist films, as well as the collaged photographs of Max Ernst and Salvador Dalí, similarly imply the blurring of time between consciousness and unconsciousness. Luis Buñuel and Dalí’s Un chien andalou 1929 alternates inexplicably between actual and slowed tempos to suggest a perceptual window into life pulled into dreaming.

The closest identification between artist and machine, however, would occur later, in the context of American Pop Art during the 1960s, which sometimes expanded the artwork’s temporal duration to spans that challenged even the most disciplined viewer. Recording New York’s Empire State Building for eight hours in a single fixed-frame shot, Andy Warhol’s Empire 1964 did not suspend time so much as film in real time – as distinguished from the representation of time in Hollywood film, which dramatises through abbreviation, jump cuts and flashbacks that serve the needs of narrative. For Warhol, the unswerving focus on prolonged temporal passages without narrative incident, as in Sleep 1963, which featured the poet John Giorno sleeping in bed for six hours (although this film, unlike Empire , makes use of edited footage and repeated passages), meant to access mechanical perception. “I want to be a machine,” Warhol famously claimed. Empire shows what it’s like to “see” as a machine might.

Other artists during the 1960s and 1970s struggled not to identify with machines, but to exploit technology to scrutinise the experience of being human. Dan Graham’s Present Continuous Past(s) 1974 creates a video feedback loop so that visitors can view themselves on two monitors, in real time and with an eight-second delay, respectively. Placed within a closed-circuit video stream, participants overcome the normal passivity of art viewing and act before the camera in order to see themselves on screen, dissolving conventional divisions between audience and performers. The time delay brings changes in self-perception. Whereas the real-time image creates possibilities for self-identification in which one’s body and image coincide – as with looking into a mirror - the delayed image shows the self as a distanced picture, one that appears part of a social group seen in relation to other visitors. Graham’s art of suspended time sensitises viewers to social experience, suggesting that restricting time to the immediate now limits consciousness to one’s solitary self.

Graham’s time-delay experiments form part of a larger reaction to Modernism’s obsession with pure presence. In the mid-twentieth century, abstract painting and sculpture were pledged to the intensity of optical immediacy, where no background subject matter was allowed to interfere with the unmediated relation to art’s materiality. Think of the New York School canvases by Jackson Pollock, Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko. As the American critic Michael Fried claimed, “presentness is grace”, by which he elevated art’s”nowness” – the opposite of time suspended – into spiritual transcendence. Like its religious precursors, the affirmation of spiritual presence denies bodily experience, tied as it is to physical process and therefore to temporal duration; to the beat of the heart.

Conducting experiments into abstraction’s musical equivalent, silence, John Cage discovered its ultimate impossibility. Despite eliminating all exterior sound when he entered the anechoic chamber at Harvard University, Cage discovered he could not purge the high-pitched noise of his nervous system and the swishing of his circulating blood. Experiencing duration at its purest coincides with the unavoidable sensation of the human body, a conclusion that Cage scripted in 1952 with his piece 4’33”, for which the pianist David Tutor sat before a piano with a stopwatch, while the audience waited. He played not a single note, elevating atmospheric noise to centre stage.

No doubt Chris Burden heard similar sounds when he placed himself in a locker for five days as a work of performance art, Five Day Locker Piece 1971, at the University of California, Irvine. “The locker measured two feet high, two feet wide and three feet deep. I stopped eating several days prior to entry. The locker directly above me contained five gallons of bottled water; the locker belowme contained an empty five-gallon bottle,” he explained. Burden’s act of endurance probably represents the limit of the art of suspending time, at least where the body must intensely experience duration. As when the artist slept in a bed placed in a gallery over 22 days without ever leaving it (Bed Piece 1972), one-upping Warhol, or had himself shot in the arm by a friend with a 0.22 rifle (Shoot 1971), lived duration would counter Hollywood fictions that represent experience vicariously. Feeling time through its exaggerated duration would allow us to live in our bodies, rather than see our bodies lived on TV.

Meanwhile, conceptual artists have explored the theoretical limits of the elongation of time. On Kawara’s One Million Years (Past) and One Million Years (Future), from 1969, were performed live in London in Trafalgar Square in 2004, taking two readers seven days of non-stop recital to recount all the years listed in the ten volumes. The average human life is equivalent to several lines, and human history transpires over a few pages. Deviating from such mathematical structure, Alighiero e Boetti highlights the chance event within expanded durations, as in his sculpture Annual Lamp 1967, where a light bulb in a wooden box randomly illuminates once every twelve months for eleven seconds.

Art during the 1980s and 1990s seemed to relinquish investigations into temporal suspension, favouring instead the mimicry of the now-time of commercial spectacle – think of Barbara Kruger’s appropriation of advertisements, Cindy Sherman’s film stills, Jenny Holzer’s LED light displays. However, the subsequent art of institutional critique expanded duration to the heights of bureaucratic boredom, which it opposed to the mind-numbing speed of pop-cultural entertainment. Consider Andrea Fraser’s service-orientated art of the 1990s, which generated surveys of arts institutions, such as the Generali Foundation, investigating their functions within a larger socio-economic framework. The art of suspending time has swelled with the growth of newmedia and digital technology, which have increasingly blurred photography and film. It appears that temporality has returned to contemporary art as an object of investigation.

On the one hand, photography has opened itself to cinematic duration. Artists such as Darren Almond and Hiroshi Sugimoto have explored the possibilities of extra-long exposure times. Taking photographs of natural landscapes bathed in the light of the full moon, Almond’s images appear mysteriously illuminated and still. Achieving similar uncanny effects, Sugimoto correlates the exposure time of his pictures of cinemas with the length of the film, yielding images of white screens, the whole movie mysteriously collapsed into a single photograph. On the other hand, artists are interrogating film’s photographic roots, as in the work of David Claerbout and Douglas Gordon. Suspending images between stillness and movement, Claerbout videotapes archival photographs, imbuing them digitally with filmic effects so that tree leaves flicker and sunlight changes over time, as in The Shadow Piece 2005. Stuck in time, the photographs are brought back to life. Gordon’s 24 Hour Psycho 1993 slows the original Hitchcock classic to a length of 24 hours, eliciting the photographic basis of film. But because the original film was transferred to digital video, Gordon’s recreation emphasises the scan lines and pixilation of electronic information, rather than the perception of film’s discrete cellular frames. The result is that while the narrative suspense of the original film is extruded by its slow progression, we experience the phenomenological characteristics of video.

The perceived escape from time may give way, finally, to hypnotic euphoria, as captured in the mesmerising cinematic richness of Dean’s Disappearance at Sea 1996, also an anamorphic 16 mm film. Focusing on the lighthouse at St Abb’s Head in southern Scotland, the work loses itself in the spinning mirrors, prisms and filaments of the optic seen at dusk. The confusion of reality and reflection disturbs the clarity of time’s progression, evoking the sensation of euphoria, of being lost in the intensity of an endless present. It may relay the state that possessed the sailor Donald Crowhurst in 1968, who inspired Dean’s piece. Engaged in a solo yacht race around the world, he lost all sense of time on the open sea, falling victim to a sickness facilitated by spatial disorientation. In a desperate act of surrender, or perhaps glorious intoxication, he threw himself overboard.