Michel Onfray on The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb 1521

Art historians don’t know what place Holbein had in mind for his The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb. A predella for an altarpiece? A free-standing work? A piece made to fit in a sepulchral niche? But the fact remains that the painting’s highly unusual dimensions (30.5 x 200 cm) make it a unique object in the history of iconography. In my eyes at least, because entering this work is like entering a coffin to see what’s happening inside. Which is nothing, apart from a dead body, a corpse – motionless for all eternity. But take a look at his face. This corpse doesn’t look as dead as all that. The mouth open, eyes too, you might just be able to hear, at least in a virtual sense, the final breath; you might guess the presence of the Holy Spirit. The viewer sees Christ seeing: he might also perceive what death has in store, because he’s staring at the heavens, while his soul is probably there already. No one has taken the trouble to close his mouth and his eyes. Or else Holbein wants to tell us that, even in death, Christ still looks and speaks. Perhaps. Let’s see.

There are three signs which indicate that this body is that of the Son of God crucified to pay for the sins of the world. Everyone knows the story. Three wounds like as many signs; three signs like as many wounds. The injuries to his side, to his hand, to his foot. None on his forehead, no traces of the thorns. Holbein paints the right side of Christ. The left, the sinistra , is in the shadow of the tomb, and hence of death. Holy trinity of wounds.

Two signs tell us that this body is also that of Man made God in order, once again, to pay for the sins of the world. Everyone knows the story. Two signs like as much flesh; two pieces of flesh like as many signs. The navel and the genitals. A protruding navel, a button on the surface of a belly of muscle, no fat – that’s the ascetic ideal for you. It testifies that even if you are born of a virgin, you’re no less of a man for that. (Only Adam should have been born without a navel. Take a look through the history of painting, he always has one.) Navel and genitals: a real membrane of flesh, not a symbolic phallus, not a shadow or a concession, but a true penis normalis – and divine, judging by the size suggested by the fabric.

In this painting, a sign may be read in both directions: Son of God or Son of Man. The hand. At least the sign made by the hand, at the exact point that divides the canvas into two parts – right and left. The middle finger outstretched, the other fingers folded back into the palm. And yet in the West this gesture is currently read as an obscenity. Because this finger is associated with penetration. Of the female genitals, certainly, but also of anything that can be similarly penetrated, even in men. Diogenes was happy enough to use his middle finger to insult Demosthenes. Christ making such a gesture in his tomb? Unlikely. Unless, a real bombshell this, he’s the antichrist! Holbein as the painter of the antichrist? We’d know about it.

Such vulgar gestures are unknown in Western iconography, it seems to me, or at least – and I’m quite sure about this – in the history of openly religious art. If you take a close look at the pagan, rustic scenes of Flemish painting, you might just spot the gesture among all the boozing, the smoking, the mischief-making. But in the painting of Christ in the tomb?

So?

So the gesture concerns not Christ made man, but the Man-God. Let’s scour the old texts that recall the Christian symbolism that has fallen into disuse, unknown even to those who claim adherence to Christianity, Kierkegaard’s famous ‘Sunday Christians’. Everything has meaning in this religion; everything is symbol, allegory; everything says something other than its initial meaning; everything hides and reveals, speaks and is silent; everything murmurs to the ear that is capable of hearing. But who is still capable of hearing today?

The hand is no longer the hand, it is more than the hand; the middle finger is not the middle finger, but more than the middle finger. Namely? Within this allegorical configuration, each finger has meaning. The hand? The soul, the principle of life. The fingers? The opportunity for a spiritual exercise – a mnemonic technique inherited from the ancients. The thumb? ‘Give thanks.’ The index finger? ‘Strive to reach the light.’ The ring finger? ‘Suffer, regret.’ The little finger? ‘Offer, propose, show, present.’ And the middle finger, then? ‘Examine, weigh.’ A lesson in edification.

Consequently, the extended middle finger in Holbein’s painting, as one might have imagined, has nothing to do with the phallic hand. At the epicentre of the work, Holbein is saying to us: ‘Look and conclude: examine.’ Examine what? This shroud on which lies the body of Christ, summoned three days later to return from death. The shroud without the body will say the body without the shroud, the resuscitated eternal body, the glorious body of the saved Christ, and therefore of the Christian-to-be, saved, if Christian he be. The middle finger acts as the punctum of the painting. The very tip, the flesh of the finger, marked by the nail like invisible writing.

This is this painting’s lesson, because every painting worthy of the name presents an enigma to be deciphered. In religious painting, the enigma is never hard to discover: it is always a lesson from the catechism, more or less skilfully disguised. Here: ‘See this shroud, it is the sign of the death of death if, and only if, you live as a penitent Christian, imitate the Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ.’

The shroud has been folded for twenty centuries, at least if we believe the Christian mythology, but this fabric still speaks. Yesterday a true icon (vera icona), soon to be Veronica, the patron saint of image-makers, today the object of pagan devotion. Even in death, Christ still speaks. Or, to be more precise, because he is dead, he will not stop speaking. Here’s a corpse that’s been pretty talkative for almost twenty centuries. But what he says seems less and less audible. Preuve au doigt et à l’oeil – tangible, visible evidence.

Jenny Uglow on M Zouch c.1538

Hans Holbein the Younger

M Zouch c.1538

Coloured chalks and black ink on pink prepared paper

29.4 x 21 cm

© The Royal Collection © 2006 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

I stand very still. He is kind, Master Holbein, but I feel awkward under his keen eye. I cannot look him in the face, which is as well, since he asks us not to gaze directly at him as he works. He is strange, with his short hair and stubble. He talks little and his accent is hard to understand. He works with his left hand, which is not the common way. And now I just wait and wait, until he is finished. I breathe in and keep my shoulders back. My thoughts turn inward, and float. No one can call me to find a book, to walk in the garden, to come to table, or to talk to the King, who likes to sit among us. I can be anyone, not plain Mary Zouch, lady-in-waiting.

This morning I plucked my eyebrows and made my parting straight and smoothed my hair. In the mirror I see oval within oval, my face like a smooth brown egg, the cap’s rim with its embroidery and arch behind. My gold necklace echoes my fair hair and the threads in my cap. Out of the corner of my eye I can see Master Holbein take a chalk the colour of peach blossom, and another of yellow for the gold.

He has painted the new Queen, my mistress – Jane Seymour as was – rich in red and gold thread, and has created a great cup for her and many jewels. At court we admire clever jewels. I look modest, with my black velvet dress tight across my breast, but my brooch speaks of romance. It shows the gallant Perseus saving Andromeda, chained to her rock where the sea monster waits. Many might want to be rescued, too, from this court of great riches and great danger, yet to me it is a refuge. After my mother died, my father married again, but his new wife was cruel, and I wept. And when I reached fifteen I begged my cousin Lord Arundel to take me from our manor at Harrington, in the county of Northampton, and find me a place in the royal service. Now all is well. The Queen has given me jewelled borders for my dress – and she is with child, and may give the king a boy, and he will rejoice and I will wait upon them until I grow old.

No, no. Everyone knows that the pale and pious Queen Jane forbids her women to wear those fashionable caps. She makes them wear the old gabled headdress with the wings folded back, so tight around the brow that foreigners cannot tell if we are blonde or dark. This is not Mary at all. It is I, Anne Gainsford, who wear the capucine that Anne Boleyn brought back from France. It is I who wear the heavy brooch, which is not Perseus and Andromeda, but Fortune on a weather vane whirled by the winds of fate. And, oh, I have been whirled about, for I served Queen Anne, with her beauty and fiery wit and insolent anger, and I spoke against her at the end, telling of her games with Thomas Wyatt, courtier-poet and married man. Now she has gone under the axe. Now I am to marry George Zouche, a gentleman pensioner of the king, and that is why I hold a carnation for marriage, and look down to the side where my husband’s portrait will hang beside mine. I will be Mistress Zouche – ‘M Zouch’ - mistress of my household, mistress of my life.

So speaks the portrait, in two voices. Mary Zouch attended Jane Seymour’s funeral when she died after childbirth in 1537, and five years later she was granted an annuity of ten pounds “in consideration of her service to the King and the late Queen Jane”. Anne Gainsford married and had many children. Both were the servants of dead queens. The beautiful drawing carries a warning. It is tempting to spin stories, to find the individual life behind a sketch as vivid as this, so expressive of the new humanist sense of the self. Yet certainty can be overturned by a detail. I was sure that this was Mary until, in another context, I found Jane Seymour’s ruling about caps. But who is to say that Mary did not put one on with glee after Jane died? It almost hurts to remain uncertain, but the only truths we can bring away are those we find within the work itself, in its making and in our own particular sense of the artist’s vision.

The drawing has its own story. Holbein kept it in his studio until he died of the plague, aged 45, in 1543. The image of M Zouch, as she was labelled in the time of Edward VI, was then bound with 84 others into a ‘Great Booke’, which wandered from hand to hand – from the Earl of Pembroke to Edward VI, then to the family of Arundel and finally back to Charles II. For a century the book lay locked away, until Caroline of Anspach, George II’s queen, roaming the corridors of Kensington Palace on a dull February day in 1727, noticed an old bureau and asked for it to be opened. And there they were, a whole sleeping court: knights and barons and squires, ladies-in-waiting, bishops and soldiers, poets and wits. Caroline framed her fellow countryman’s sketches and hung them in her favourite home, Richmond Lodge. But as times changed, so did royal tastes. Back went the Tudor court into the dark, entombed in the print room designed by Prince Albert at Windsor. And there rests our heroine still, encased within great glazed cabinets and stout castle walls. Mary or Anne, still waiting.

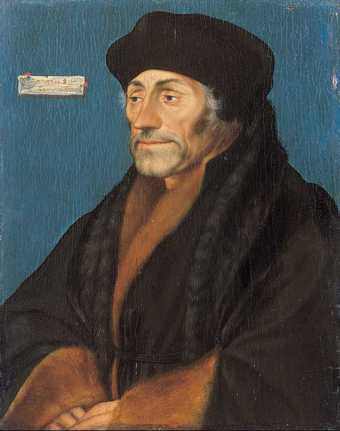

Chuck Close on Erasmus of Rotterdam 1523

Hans Holbein the Younger

Erasmus of Rotterdam 1523

Oil on wood

18.7 x 14.6 cm

Photo: 1989 The Metropolitan Museum of Art © Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Robert Lehman Collection, 1975

There is amazing verisimilitude in this tiny painting. The fur is furrier than the way any other artist paints fur. The gold shines more than most any other artist’s gold. There is a great sense of compressed energy packed into a small space.

It has such presence because the flat background, which is a strong blue colour, pushes the image forward to make it much more confrontational. Holbein has painted both the front and the back of the head (most artists of this period just painted the front), which means it occupies more space and is more lifelike. You know from his sophisticated drawing what is going on underneath the face – from the way the skin is stretched over the teeth or the chin wraps around the bones. Look at the eye socket and how the eye is located – you almost expect it to turn around and stare at you.

What makes the picture especially human is that he has not been particularly flattering. Compare it with, say, paintings by Lucas Cranach, where all the characters could have come from central casting – everybody looks the same. Holbein’s portraits are always very specific personalities. Having said that, I am not really that interested in the biographical aspect of these pictures, or in the artist’s friendship with Erasmus. I am a kind of dyed-in-the-wool formalist when I look at a painting. I am more interested in the paint handling, the drawing, the composition. Painting is such an incredible act and obviously the most transcendent of all the media. It transcends the physical reality of what is being portrayed – you can relate to life experience, and paintings can make you cry. When a painter looks at another painter’s work, even across the centuries such as this, it must be like when a magician performs in front of an audience of other magicians. The question arises – do they see the illusion, or do they see the device that made the illusion? I think when painters view someone else’s painting, they are simultaneously aware of the image that was built and how it was built. For me, the magic is in seeing how the apparition appeared within the rectangle; what the pictorial syntax is; what the mark-making methods are; what the touch is. Holbein has an amazing touch – it is almost invisible in something this small. It is as if it has been blown on to the painting by a gust of wind. How the hell would this happen?

In this picture there are no individual brushstrokes that signify one hair. So how did he get it to look like fur if the marks are not symbolic; if the mark does not stand for fur? He paints the situation rather than the symbols of fur.What does that mean? Well, when light falls on something made up of lots of little stuff, it becomes very soft. It hits some of those hairs and falls between the others, casting a shadow. Think of the difference between a telephone pole casting a shadow on a street and then on grass. The shadow on the street has a hard edge, but the minute it hits the grass, the edge becomes soft. You do not have to paint every blade of grass to get someone to understand that they are looking at grass – you paint the situation of grass. It lights differently, and shadows fall differently. That is what Holbein has managed to do here. Compare this to, say, a painting of an apple tree by Grandma Moses. She will make the trunk and then the branches, and she will hang the apples on it. And you count the apples in the painting and that’s how many are on the tree, because she is literally hanging these things. In fact, some of the apples would be behind others, while some would be hidden by branches, but a naïve or folk artist tends to paint symbolically – each mark stands for something. Andrew Wyeth is, in many ways, like a naïve painter. You can count the blades of grass that Christina is crawling on going up the hill in Christina’s World 1948. If you study more sophisticated paint handling, you won’t have a mark equalling one thing.

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Three Princesses of Saxony: Sibylla, Emilia and Sidonia c.1535

Oil on limewood

62 x 89 cm

© Courtesy Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Look how Holbein has painted the velvet of the man’s collar. Velvet has lots of little hairs that stick up, and each one casts a shadow. Seen together, it makes this soft surface, which breaks in a certain way when folded (silk, on the other hand, folds on a sharp edge). We are very sophisticated in reading these things. The paint handling and pictorial syntax is so much of what our experience of the painting is about. Think about it in literature. Hemingway’s distinctive economic use of words can make a simple story of a bullfight riveting because of the way they slam together and trip off your tongue.

The enduring allure of Erasmus can also be attributed to the fact that it is in such good condition. Holbein mixed a lot of oil and varnish into the paint. If you look at the picture from below, you can see that part of the physicality of the piece is that it is glazed with a very liquid medium – unlike Botticelli’s application of paint, which is so dry that when you view his canvases you feel you need a glass of water. In this work it is so rich that it’s as if we are watching over his shoulder while he’s creating it. For me, this makes his painting a contemporary experience, because it is a record of the decisions he made and is in virtually the same condition as it was when he produced it.

As well as Holbein’s use of paint, his composition is incredible. Everything in the picture is sliding under these shapes of the fur collar, leading your eye up the collar to the big mass that is his head. It almost looks like a lily opening up; like a painting by Georgia O’Keeffe – the gap between the collar could be a gully with water rushing through it, the head a dark mountain range. To me, that abstract flat reading is very important to this painting – it comes out at you; some of the shapes resemble something else, and then you settle into the picture for what it really is.

George Carey on Portrait of William Warham 1527

Hans Holbein the Younger

Portrait of William Warham 1527

Oil on panel

82.5 x 66 cm

© Courtesy Musée du Louvre, Paris/Bridgeman Art Library

To a contemporary Archbishop of Canterbury there is something comforting about William Warham, because he too lived at a time of great uproar, with increasing tension and uncertainty. Luther’s Reformation was far off when Warham took office, but half way through his reign (from 1503 to 1533) the traditionalist archbishop had to face the challenge of profound change, which eventually led to new ideas coming from the continent.

If that were not enough, he was eventually overshadowed by Thomas Wolsey, who, in addition to being appointed Chancellor by King Henry VIII, was made cardinal in 1515 and took centre stage as far as church affairs were concerned. The inevitable result was that Warham’s position was hopelessly compromised and his office belittled and embarrassed. A kindly and godly man, he found himself outwitted and humiliated by his more ambitious and worldly fellow cleric. One commentator states accurately: ‘The liberal man is always at a disadvantage when confronting naked power.’

In his final years as archbishop, Warham had to confront major upheavals in both the nation and the church. His sovereign was one of the most cruel and frightening of all despots, while at the same time he was caught between the absolute power of Rome and those in society and the church calling for reformation – a purging of ecclesiastical power and freedom to believe and read the scriptures liberated from church interpretation.

The gentle Warham was rather too weak for the demands of his day. If he preferred a good strong fence to sit upon, rather than play the martyr, as was the case with Thomas More, St John Fisher or even Cranmer, then most will sympathise with him.

For myself, being archbishop 500 years later, I echo his disdain for the corrupting influence of power in the state and church. In 1993 the Church Commissioners lost £800m through poor investment at a time of plummeting share prices. The church was shown in a very poor light because of its eagerness to make as much money as possible for its clergy, using dubious means. This led to reform as an Archbishops’ Council was created to bring money and policy together.

No doubt Warham would have been shocked by the ordination of women to the priesthood that happened in my time. I was quite sure this was long overdue. In his own day he would have found it unthinkable, but I believe he would have perceived a familiar factor in this issue – how does one balance traditions and truths that we have received from the past with new ideas, truths and opportunities coming to us in the present age?

And what would he have made of the media, with its insatiable appetite for news, controversy and sensationalism? Perhaps he would have given a wry smile as he sees modern archbishops prodded by their press secretaries to give sound bites or to face a sharp and aggressive John Humphrys on the Today programme. ‘Ah,’ he might say, ‘I knew this is what Caxton’s invention would lead to!’

So I do feel a sense of affinity with Warham. Like those who preceded and follow him, he sought to serve the same Lord with all the frailty of human nature.

Now I know why you look so pensive and troubled, William, in your portrait by Holbein. You had a lot to contend with. Your successor crumbled before Henry VIII because of his ‘great matter’, and the church split in two. Indeed, I am on the other side. Gradually, the Church of Rome and the Church of England are drawing closer, but it will be a long time before we shall have a united church in this land.

But, William, I have to say that I preferred my time as archbishop to yours. So, thank you – and, in the Communion of Saints, do spare a thought for me and my successor Rowan Williams.

Derek Wilson on Allegory of the Old and New Law early 1530s

Hans Holbein the Younger

Allegory of the Old and the New Law Early 1530s

Oil on panel

50 x 60 cm

© Courtesy the National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

When we stand before this painting we have travelled only a few paces from those familiar portraits Holbein created to satisfy status-conscious patrons, but the conceptual journey we have taken could scarcely be greater. In the paintings of king, queens, courtiers and merchants, the great, the good and the wealthy in their silks, furs and jewels demand to be recognised as people of substance and importance. In Allegory of the Old and New Law Holbein shows us representative man, stripped naked and huddled before the eternal realities of life, death and faith.

This is a painting that takes us to the very heart of the Reformation conflict – a painting of two halves in which the messages of the Old and New Testaments are juxtaposed. On the left Adam and Eve sin and, thereby, are doomed to death. Moses receives the Ten Commandments and when the Israelites transgress (and, therefore, begin to die) he raises up a brazen serpent: they can be delivered by simply looking at it. The counter-balancing elements to the right show the apostles pointing to the cross, which mirrors the serpent. Those who embrace the sacrifice of the Lamb of God will live. On a mountain top opposite Mt Sinai and Moses, Mary and the host of heaven receive salvation through divine grace (and not law). On the left the ultimate fate of man is mors, but on the right Christ rises triumphant from the tomb.

Allegory of the Old and New Law is a didactic, pictorial representation of the central Lutheran doctrine of salvation by sola fidei – faith alone. To avoid any possibility of misunderstanding, the message is hammered home by Latin inscriptions. Homo laments in the words of St Paul from Romans 7:24: ‘Wretched man that I am, who shall deliver me from this body of death?’ By way of reply Isaiah and John the Baptist point to Christ, the former prophesying the virgin birth and the latter declaring: ‘Behold the Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world.’ Clearly the artist had a firm grasp of Lutheran teaching and the biblical testimony on which it rested. The painting was done in the early 1530s, presumably as a devotional picture for an educated adherent of the new faith who understood Latin. Beyond that we know nothing about the circumstances of its creation.

However, the work itself contributes significantly to our understanding of Holbein’s own religious pilgrimage. Basel, where he spent most of his early adult years, was one of the intellectual nurseries of the Reformation. Here the great humanist scholar Erasmus found refuge from the forces of Catholic reaction, but here also were the thriving printing houses of Amerbach, Froben and Petri who were busily turning out the works of Luther and other evangelical controversialists. Basel was a city of exciting, free debate, and one which was moving, under the spiritual leadership of Johannes Oecolampadius, to the more extreme evangelical position of Ulrich Zwingli. It was a fertile breeding ground of religious innovation and Holbein could not but be involved in the buzz of new ideas.

During his first short stay in England (1526–8), Holbein enjoyed the patronage of Thomas More and his circle, but London became too hot for him when More committed himself to the persecution of heretics. He spent the next three years, during which More was Lord Chancellor, back in Basel. In his absence the Swiss city had undergone a root-and-branch reform. All churches had been purged of religious imagery. The artist seems to have found it difficult to adjust to the new regime, and when he heard that Henry VIII was moving towards an understanding with the German Lutheran princes, he thankfully returned.

He fell out with the humanist circle – Erasmus was quite bitter about the painter’s ‘desertion’ – but under the patronage of the king, the Boleyn family and Thomas Cromwell (principal architect of the English Reformation), Holbein prospered greatly. He produced, among other works, woodcuts for the first English Bible and illustrations for evangelical propaganda pamphlets. This is the background for Allegory of the Old and New Law. The artist was at home with the teaching of Luther (who was certainly no iconoclast), and willingly lent his pen and brush to propagating the views of the German reformer. This painting is a version of images produced in Wittenberg by the elder Lucas Cranach, Luther’s friend and ally. Yet there is one marked difference. Holbein shuns an element common to other Lutheran propagandists. They underscored their message with lurid scenes of sinners entering the maw of hell. For Holbein the last enemy is death, a theme he returned to on many occasions, most notably in the superb Dance of Death engravings and in what many have seen as his most remarkable painting, The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb 1521, which is his ultimate expression of religious truth, stripped of dogma.