‘Christ, they’ve really done a job on this place,’ remarked the police officer who visited Jake and Dinos Chapman’s Peckham studio after it had been burgled. Though there had been a break-in, the mess that caught the officer’s eye was, in fact, the normal state of the studio floor: ‘A sediment of Goya pictures,’ as Jake Chapman described the scattered debris, ‘heaped in layers.’ According to the art critic Richard Cork, the Goya books that the brothers had carved up and scattered around to make their disorderly image library were all ‘smeared and splashed with blood from cuts in the Chapmans’ fingers as they worked on the images with scissors, razors and paper knives’.

The Chapman brothers, fresh out of the Royal College of Art, had become obsessed with Goya’s gory oeuvre – to the point, as Jake Chapman told me in a phone interview, that they later even considered changing their surname to Goya. They were especially haunted by the famous series of etchings known as The Disasters of War, in which Goya portrayed the atrocities he had witnessed in the Peninsular War between Spain and France (1808–14) with a visceral horror. In his book on Goya, Robert Hughes claims the series is ‘the greatest antiwar manifesto in the history of art’. Goya’s sardonic titles offer a cumulative sense of terror: ‘This is bad,’ warns the caption to a picture of a monk stabbed through the heart by a French sabre; ‘This is worse,’ reads one of a Spaniard who has been impaled on a tree from his anus to his throat; ‘One can’t look,’ declares another, beneath a group pleading for their lives as a cluster of bayonets appears through the edge of the frame. The Disasters of War was deemed too horrific to be shown in Goya’s lifetime, with the prints being published for the first time in 1863 – 35 years after his death.

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes

Plate 39 from The Disasters of War 1810–20 (first pub. 1863)

Etching, fine and large grain aquatint, hatching

15 x 20 cm

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Goya’s use of art as a provocation has inspired the Chapmans, who are well known for their aggressive use of shock tactics, to create works of ‘vertiginous obscenity’, as they term them, from their earliest days. Returning to The Disasters of War repeatedly for more than a decade, they have adapted Goya’s example for contemporary impact. To the Chapmans, his unflinching aesthetic was ahead of its time; they praised him as ‘the first Modernist artist; the first who had psychological and political depth’. ‘Goya is the black source of the grim stream,’ wrote the art pundit Matthew Collings. ‘He’s at one end and Jake and Dinos Chapman are at the other.’

Other artists, such as Jeff Wall, who made a composite photograph called Dead Troops Talk in 1992, have been inspired by The Disasters of War, but the Chapmans have appropriated it almost as obsessively as Picasso did Manet’s once controversial Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (Picasso made 157 drawings, 27 paintings, six linocuts and five sculptures after Manet’s painting). ‘Our work proceeds more by compulsion than by inspiration,’ says Jake Chapman. He offers as an example the story of Beckett’s Molloy, who moves stones from pocket to pocket, sucking each one as he goes. ‘As he circulates these stones, all kinds of complex patterns emerge; meaning emerges out of all the combinations and variables.’ In a piece entitled All of Our Ideas for the Next Twenty Years 1997, the Chapmans included their own reworking of Goya. You might say that if you understand their use of Goya, you will understand their work as a whole.

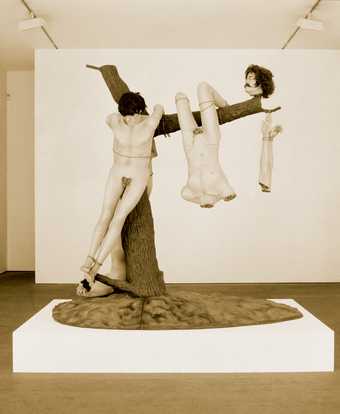

In 1993 the brothers re-created The Disasters of War as a series of miniature tableaux. They melted down toy soldiers, twisting, maiming and painting them to resemble Lilliputian versions of Goya’s prints, each intricate and bloody scene enshrined on its own little island of mossy green. The following year they re-created plate 39 of The Disasters of War – Great Feat! With Dead Men! – on a larger scale, using nylon-wigged mannequins. Great Deeds Against the Dead 1994, which was their contribution to the legendary Sensation exhibition at the Royal Academy, depicts three naked male bodies bound to a tree; blood dribbles from the crotches of these shop dummies where their genitalia would have been, if they’d ever had them. One victim’s arm dangles by its fingers from the makeshift gallows alongside the carcass of his torso, the severed head skewered on a branch.

Jake and Dinos Chapman

Great Deeds Against the Dead 1994

Mixed media

277 x 244 x 152.5 cm

Photo: Stephen White

Courtesy Jay Jopling/White Cube (London) © Jake and Dinos Chapman

The Chapmans once told the art critic Robert Rosenblum that Great Feat! represented a secular crucifixion, ‘because the body is elaborated as flesh, as matter. No longer the religious body, no longer redeemed by God. Goya introduces finality – the absolute terror of material termination’. There is something troublingly artful about the arrangement of the figures. They have been posed by their murderers – as a warning to others – in a gruesome echo of the classical statue of Laocoon and his two sons writhing in the coils of a huge serpent. Robert Hughes wrote of Goya’s macabre trio: ‘They remind us that, if only they had been marble and the work of their destruction had been done by time rather than sabres, neoclassicists. would have been in aesthetic raptures over them.’The Chapmans realise the fragmented classicism hinted at in Goya’s print in the heroic scale of their sculpture, but they mean the magnification to assault rather than uplift the viewer.

In Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag wrote that, unlike most images of mutilation and torture, Goya’s The Disasters of War ‘cannot be looked at in a spirit of prurience’ – it is devoid of pornography. The Chapmans, who have endlessly returned to Great Feat! with a rubber-necking insistency, would disagree. ‘I don’t think that there’s an opposition between a salacious interest and a noble one,’ Jake Chapman says. For them there is a ‘convulsive beauty’ in the violent image, and they are wedded to the Surrealists’ avant-garde belief that such shocks and jolts can wake us from the dream-state of a commodity culture by, as Jake puts it, ‘shocking the viewer from the edifice of comfort’. (The brothers’ work might be collectively titled The Disasters of Capitalism.) ‘He’s defended as a humanist,’ Jake once said of Goya’s prints, ‘but there are moments of pleasure. They have an intensity, a humour and a tendency to undermine their own dignity.’

Their first work to arouse controversy, Great Deeds has become something of a trademark for the Chapmans, even though it refers to a work by another artist, and they have frequently quoted it in their subsequent art. For example, Hell 1999–2000, an apocalyptic scrum of 5,000 miniature figures, included an explicit quotation of Great Deeds. (Almost too fittingly, perhaps, Hell was destroyed in the Momart warehouse fire in May 2004. It is being rebuilt, seventeen per cent bigger.) In one of the Chapmans’ doodles of Fuck-face 1994, a figure with a dildo nose and a sphincter for a mouth made the same year as Great Deeds, the figure no longer wears a t-shirt emblazoned with the artists’ manifesto – the first line of which reads: ‘We are sore-eyed scopophiliac oxymorons’ – but one with a logo version of Great Deeds. The Chapmans point to Goya as a forebear to their more disturbing sculptures, like this one, almost as if to justify their assault on the aesthetic sensibility of the viewer.

Jake and Dinos Chapman

Detail from Hell 1999–2000

Glass fibre, plastic and mixed media

© Jake and Dinos Chapman

In Year Zero 1996, whose title is the name to which Pol Pot gave his genocidal dream for Cambodia, Goya’s gallows tree becomes a climbing frame for three children, naked except for clumpy trainers. One of these prepubescent mannequins, who is related to the Chapmans’ other Hans Bellmer-like aberrations, hangs upside down so that her long hair almost touches the floor in an obvious allusion to Goya’s headless piece of meat. In their disturbing Disasters of yoGa 1997 – a ‘dyslexic disruption’ of Goya, in their own description – a genetically mutated mannequin bends back into itself and seems to give birth to its own head. When Great Deeds Against the Dead was first shown, the police paid a visit to the Victoria Miro Gallery in answer to a visitor’s charge of obscenity. They were appeased with startling ease when they were shown that the Chapmans’ chamber of horrors was based on Goya’s print. ‘They left with an image of the Goya,’ Jake recalls, ‘so it was historical authenticity that gave us licence.’ (Anthony Julius has referred to this strategy as the ‘canonical defence’ of shock art; another defence, as Matthew Collings remarked in relation to this sculpture, is to insulate the work with ‘ironic discourse goo’ – quoting from Bataille and Kristeva to make it ‘cool rather than just horrible’.) But Great Deeds is, if anything, more kitsch than shocking – Goya meets Jeff Koons.

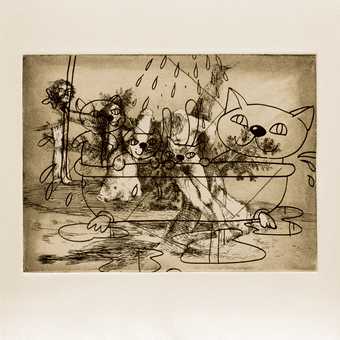

Jake and Dinos Chapman

Gigantic Fun 2000

Etching from a portfolio of 83

37 x 42.3 cm

Photo: Stephen White

Courtesy Jay Jopling/White Cube (London)

© Jake and Dinos Chapman

In 1999, in a series of 83 etchings plainly titled Disasters of War, the Chapmans began to take on Goya’s masterpiece in his own medium (hadn’t Goya, after all, copied Velázquez in his first etchings?). In their first graphic version of Great Feat! Goya’s print has been amateurishly traced and a swastika carved into the plate over the image. The result resembles the famous SDP anti-Hitler election poster of 1932, which shows a worker crucified on the wheel of a swastika. But in this case, the image is reversed in printing, so that the Goya appears as if in a mirror, and the swastika – an ugly neo-fascist desecration – has been transformed into the Hindu symbol of peace (‘Indian for have a nice day,’ as Jake Chapman puts it). In a tinted version, made in 2000, a crowd of silent witnesses looks on, casting long shadows up to the blood-spattered group; in Gigantic Fun 2000 the print has been overlaid with a picture plundered from a child’s colouring book featuring some malevolent-looking cats in a bath. In 2001 the decapitated head is overlaid with a painted one with goofy ears, a red nose and the sort of grimace that the cartoonist Steve Bell might have given Tony Blair.

Jake Chapman, Dinos Chapman

Disasters of War (1993)

Tate

All these variations on a theme were a rehearsal for Insult to Injury 2004, for which the brothers bought a series of The Disasters of War for £25,000 – printed in 1937 from original plates – and systematically defaced it, adding the heads of Mickey Mouse and grinning clowns to the figures, covering Goya with a graffiti of gas masks, bug eyes, insect antennae and the ubiquitous swastika. (They later created a similar work using Goya’s Los Caprichos series, called Injury to Insult to Injury.) The Chapmans were condemned in some corners of the press for this act of vandalism. They answered their critics with the ‘canonical defence’, this time citing Robert Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing of 1953, for which the artist asked de Kooning to donate a valuable drawing so that he could create a new work by erasing it, to justify their attempt to eclipse Goya.

The Chapmans’ ‘rectification’, or ‘improvement’, as they termed their adaptation, revealed their ambivalent relation to the master; they mocked their endless return to Goya in the title of an exhibition of these works, ‘Like a Dog Returns to Its Vomit’. It is as if they couldn’t shrug off his influence, however hard they tried, and where this was once reverence, they had been haunted by Goya to the point of iconoclasm. When asked if he’d have liked to have met his mentor, Dinos Chapman replied: ‘I’d like to have stepped on his toes, shouted in his ears and punched him in the face.’

Almost a decade after their first Great Deeds Against the Dead, the Chapmans created another version. They seemed finally to have made Goya’s image their own, unpicking it and transforming it into a seething mass of decomposition. Sex I 2003 resembles the extravagant images of death that are constructed in papier mâché in Mexico to celebrate the Day of the Dead. It shows Goya’s three rotting victims being licked clean by an army of insects and slithery creatures that come in waves of putrefaction; a swarm of maggots, snails, flies, rats and spiders, each one a prop acquired from a Halloween shop and individually cast in bronze. A sated raven sits menacingly at the top of the tree.

After years of battling the image, they appear to have overwhelmed Goya’s original with their own brand of pornographic Surrealism. Indeed, now the Goya they refer to is the one they have already reinvented: a rotting severed head rudely spiked on a branch, the only patch of flesh still to be eaten, has been given Spock ears, a red nose, horns and a deathly grin.