Peter Fischli and David Weiss

Image from Untitled (Flowers) 1998

Series of colour C-prints

Each 125 x 190 cm

© Art Collection Deutsche Börse/courtesy Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich © Peter Fischli and David Weiss

Peter Fischli and David Weiss’s film The Way Things Go 1987 plays continuously on an overhead video monitor in the waiting area at Tekserve, the leading Apple Mac repair shop in Manhattan, and is known to many thousands of customers. It’s a very busy place. You walk in with your crashed computer, take a number, settle in and prepare to wait, hoping in the end to discover the problem isn’t fatal. Meanwhile, you’re distracted from your troubles by the zany film that features extended tour de force chain reactions in which everything in the artists’ studio gradually self-destructs. It’s your worst nightmare, and these guys are making fun of a doomsday scenario that could very well be your own. In spite of yourself, you have to laugh – you and countless anxious others who’ve been willing to watch the movie without taking on the extra added burden of knowing who the artists are, or what conceptual art might be, and whether or not this is it.

Peter Fischli and David Weiss

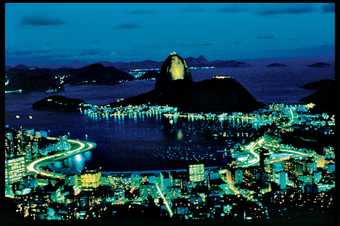

Image from Visible World 1987–2001

Series of 3,000 slides

© Courtesy Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich © Peter Fischli and David Weiss

The way things go, and don’t – that’s life. In its totality, life is more than we can fully grasp; and yet in all its mundane aspects and repetitiveness, it’s filled with negligible details. Between profound meaning and meaninglessness, there’s room for irony, and it is well-inscribed in Fischli/Weiss’s early art. Their perennial interest in the everyday – the more ordinary, the better – is both a ground for their activity and a conduit to higher awareness. This is the jumping off point for their trompe l’oeil installations, including their 1994 exhibition at the Sonnabend Gallery, in which the appearance of an empty gallery, or one under construction, had the capacity to render viewers temporarily mute. At a time in New York when the art world was obsessed with institutional critique and questions about what pundits like to phrase ‘the real’, it ranked as one of the great shows. Instead of order, there was disarray. The place resembled a construction site more than an art exhibition. It was littered with building materials, tools and trash, and looked as if the crew had been abruptly called to another job, or maybe they were just on a break. Even though it was full of stuff, the site felt empty and abandoned. Was it our mistake? Had we arrived between shows? Was it the wrong gallery? With the art apparently missing in action, viewers were left to ponder their own deflated expectations.A moment later, we realised the nature of the installation, seeing that absolutely everything was simulated (that is, made by hand), and found ourselves asking: ‘Is anything real? What constitutes real in art?’ Given the times, these questions couldn’t have been more loaded.

The trompe l’oeil works related to a genre of art represented by a different tier of galleries that were, logistically speaking, practically next door to the Sonnabend in the SoHo decades of New York in the 1980s and 1990s. Known locally as ‘schlock’ galleries, they catered to tourists, often specialised in art that fools the eye and contributed as much to the ambience and mix of the neighbourhood as their blue-chip counterparts, with whom they rubbed real estate shoulders. The distinctions between schlock and blue-chip were sometimes razor-thin: Andy Warhol, for example, liked to sell his work at both. For purposes of comparison, the galleries might be divided into those that left viewers alone and those whose sales staff were trained to pounce and deliver a sales pitch the minute a warm body crossed the threshold. Fischli/Weiss in SoHo – that was the perfect situation to question distinctions between high and low art; to put taste to the test. Was the difference between high and low a matter of substance, or rhetoric, or sales pitch?

Twenty years down the road, SoHo is not what it used to be; Chelsea is far more upscale and corporate. Even so, Fischli/Weiss continue to ask the same questions about reality and perception. Their interest in vernacular culture is as pronounced as ever. Fotografias 2005, a collection of black-and-white photographs of wall murals taken all over the world, offers both random and in-depth coverage of home-style, folk-commercial art culture. They have also expanded their repertoire to include compendiums of gorgeous images of gardens, flowers, animals, the countryside, the four seasons – whatever catches their eye.

Peter Fischli and David Weiss

Image from Fotografias 2005

Series of 109 photographs mounted on white paper

Each 10 x 15 cm

© Courtesy Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich © Peter Fischli and David Weiss

In 1999, for their first exhibition at Matthew Marks Gallery in Chelsea, they showed more than 100 colourful, double-exposed photographs of flowers, hung floor to ceiling. The impact was overwhelming. Their luscious colours and beautiful subject matter brought into focus a little pocket of reverie,a mini-Xanadu. Some would call it beauty, though others might term it kitsch.

The artists gather visual material in and around Switzerland, and in their travels throughout the world they take copious numbers of photographs, which find their way into their current multimedia installations. The flowers, for example, were photographed in Zurich and one of its suburbs. Pictures of flowers, albeit double exposures that create beautiful-absurd hybrids, are primed to fit into the category of “best loved images of all times”, as you might find in a local camera club newsletter to herald the arrival of spring. Given their overlay with mass cultural tastes for pretty pictures and the high cliché potential, do Fischli/Weiss’s flower portraits flirt with irony?

From their photographs of busy airport runways to the purple haze of sweet pea blossoms and the pink blur of peony petals; from investigation to reverie – that’s the leap we’re currently mapping in the work of Fischli/Weiss. Concerning sweet peas and peonies, as we examine the visual paradise that has begun to emerge in, and as, their art, it’s important to note that, increasingly, it looks like, well, Switzerland. Both real and imagined, the idea of their homeland is conveyed in the flowers, plants, gardens, mountains. Even a chunk of cement presented by Fischli/Weiss in 2005 as an outdoor sculpture, when sufficiently watered and weathered and carpeted with moss, is meant to represent a topography that approximates the natural beauty of the Swiss countryside.

What is ordinary in Switzerland is not in other parts of the world. Untrammelled nature, pleasure gardens, leisure (that’s part of the picture too) – these qualities might be close enough to fragments of everyday experience to be considered as regular, and even real. At the same time, however, Fischli/Weiss’s pictorial cornucopias describe places and experiences that qualify as decidedly idyllic, with the caveat that the artists are far less prone today to formally fix the line between what’s real, what’s ideal – and what’s not.