As an American artist and essayist, I have always been fascinated by the links between early nineteenth-century English popular culture and current American phenomena. My one-hour video Rock My Religion makes a connection between religious and later rock ecstatic revelation and the Industrial Revolution.

John Martin’s wonderful painting of the Apocalypse, The Great Day of His Wrath 1851–3, which I saw at Tate, really ‘turned me on’. The first edit of Rock My Religion had images shot at the gallery of the picture placed after initial footage of an early industrial age mill on the outskirts of Manchester. Next came images of a Shaker settlement (the founder of the Shakers, Anne Lee, emigrated to America from Manchester). I believe Martin’s work is the first shell-shocked reaction to the anguish of the new industrial age, and also the first lurid science-fiction-like painting. He was influenced, in his depiction of the Book of Revelation, by both William Blake and Mary Shelley’s early sci-fi novel, The Last Man 1826. His painting, related to the Luddites’ rejection of the machine age, is a vision of hell on earth leading to an apocalyptic disaster.

Dan Graham

Rock My Religion 1982–4

Black, white and colour film with sound

Film still

© Courtesy Lisson Gallery, London © Dan Graham

When I was thirteen, I listened to a radio broadcast by the American evangelist Herbert W. Armstrong. His programme, The World Tomorrow, depicted the coming end of the world as described in the Book of Revelation. We Americans thought that the end of the world would be brought about by nuclear warfare between the USSR and the USA. Relating to more recent events, Martin’s paintings remind me of the American and British coalition’s operation of ‘Shock and Awe’: the initial assault on Baghdad.

Like Turner’s embers, smoke and steam paintings about the early locomotives, Martin’s lightning and fire skies are a fearfully realistic (as well as phantasmagoric) depiction of the New World Order in the process of coming to fruition. The English science-fiction writers Michael Moorcock and Brian Aldiss have mentioned the paintings of Turner as an inspiration for their form of time warp fantasy. Martin’s paintings are more like lurid paperback covers of cheap American popular sci-fi. The theatrical nature of his spectacles is closer to Hollywood epics than to Blake’s drawings. He is almost realistic in his representation of nineteenth-century England’s teaming crowds, pestilence and the general misery of the masses. In a companion painting at Tate Britain, The Plains of Heaven 1853, he depicts spring in the Alps-like landscape with naked cupids and dancing maidens in white dresses enjoying a 1960s-ish hippie ‘Be-in’.

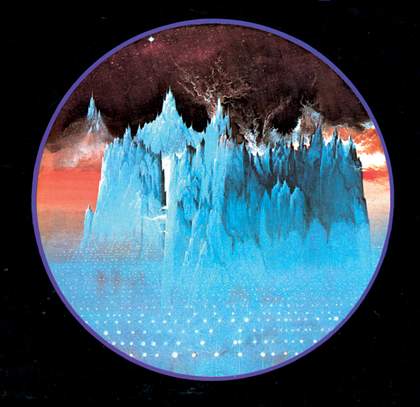

Geoff Taylor

Cover detail, Perilous Planets, edited by Brian Aldiss 1978

© Geoff Taylor

Biblical and science-fiction visions come together again in Martin’s watercolour The Last Man. His sources are Shelley’s novel and Thomas Campbell’s poem of the same name. Brian Lukacher writes in Nineteenth Century Art: A Critical History that this work resembles twentieth century science-fiction in its depiction of ‘the ravaging of the earth and civilisation by the plagues and ecological disasters… the death of nature. Shelley pictures The Last Man… [having] the tragic pleasure of surviving global ruin’. Shelley’s protagonist explains:

Time and experience have placed me on a height from which I comprehend the past as a whole, and in this way I must describe it… the vast annihilation that has swallowed all things – the voiceless solitude of the once busy earth, the lonely state of singleness, which hems me in… and mellowing the lurid tints of past anguish with poetic hues, I am able to escape from the mosaic of circumstance, by perceiving and reflecting back the grouping and combined colouring of the past.