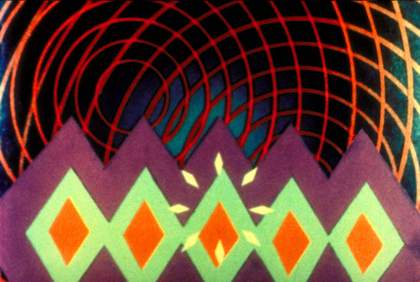

Imagine a series of white and pale green lozenges, irregularly distributed across a larger rhomboid shape composed of rectangles divided into red and deep green, at each of whose tip hovers a scattering of white diamonds. All this sits atop a purple square placed askew on a black rectangle. Blue circles emanate from the centre of the image. Imagine, then, how a fraction of a second later these lozenges, rectangles and circles spin away, shape-shifting into triangles and spirals, curves and lines, mutating their colours and forming new combinations. This geometrical drama happens again and again, lyrically pegged to the booms and trills of music. This is animated Kandinsky, or rather a scene from Oskar Fischinger’s animated 1936 film Allegretto.

Oskar Fischinger

Composition in Blue 1935

Colour, sound 35 mm film

Film still

© Elfriede Fischinger Trust/courtesy Center for Visual Music

The comparison is not flippant, and Kandinsky had the opportunity to make it himself, for it is reported that he enjoyed a screening of Fischinger’s Composition in Blue (1935) in Paris. Fischinger (1900–1967) was known to the Bauhaus milieu: his acquaintance László Moholy-Nagy screened his abstract animations and synaesthetic optoacoustic experiments at the institute. In turn, Fischinger, who began his career as an animator in Weimar Germany of the early 1920s, was, according to the film scholar William Moritz, influenced by Kandinsky’s theories of the spiritual nature of art, whereby it is a means to a higher truth created by the mystical figure of the artist. At various times in his 40 years of filmmaking Fischinger found himself confronted with Kandinsky. Certainly he had seen the artworks at close range. He visited, for example, Rudolf Bauer’s private gallery-villa. Here in this salon for abstract art, supported by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, were several Kandinsky canvases alongside other non-objective paintings. Fischinger could refer to the artist’s work at will, for he kept in his possession a Bauhaus catalogue with colour lithographs by Kandinsky, Hirschfeld-Mack, Albers and others, given to him in 1936 by the gallerist Karl Nierendorf. A later encounter with Kandinsky is revealing. In 1948 Fischinger made seven collages. He clipped reproductions of paintings by Kandinsky and Bauer from old Guggenheim catalogues and stuck on to them cut-outs of Mickey Mouse and Minnie Mouse snipped from Walt Disney comics. In one collage Mickey stares in horror at the black scribbles at the centre of Kandinsky’s Black Lines 1913, while Minnie points disapprovingly at the knotty mess behind her. The worlds of abstraction and comics collide.

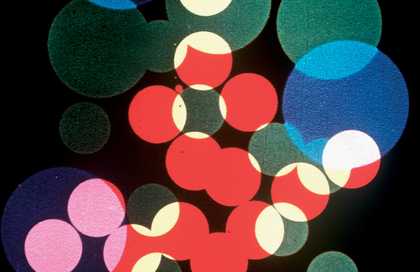

Oskar Fischinger

Circles 1933

Colour, sound 35 mm film

Film still

© Elfriede Fischinger Trust/courtesy Center for Visual Music

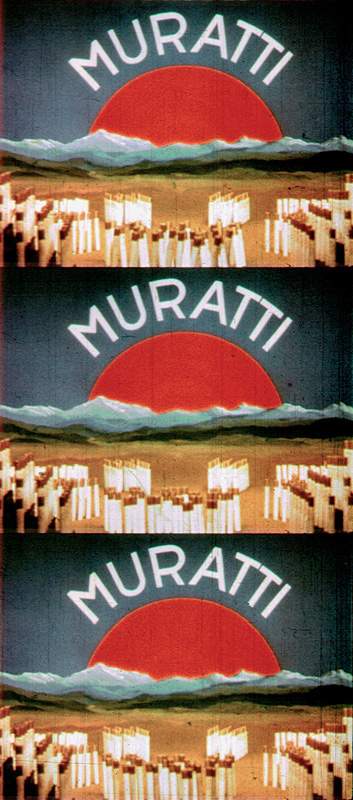

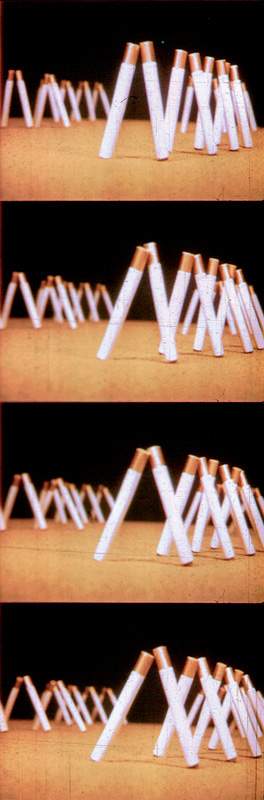

This collision between high art abstraction and mass commercial culture is emblematic of Fischinger’s career. Parallel to his experiments in abstract animation (or what he called “absolute creation”), he contributed to commercial culture in the 1930s. In 1933 he made a film called Circles. Pulsing rings alter their colour and texture as they spin through vortices and are affected by the shapes that bombard them. Only at the close was it apparent that this play of form and colour was hitched to commerce. The line “Tolirag reaches all circles of society” turned the filmstrip into an advertisement for an advertising agency. This was expedient. As an advertisement, the film evaded the usual censorship restrictions against “degenerate” art, promulgated by the new Nazi government. Fischinger continued to place his animating skills and geometric fascination in the service of commerce in further innovative advertisements in the mid-1930s. Pink Guards on Parade, for example, converted the delirious play of spirals into twirls of pink toothpaste squeezed from tubes. Geometrical abstraction found real-world analogues. Sympathetic critics tried to shield Fischinger from the ban on abstraction imposed by Goebbels in 1935 by labelling his films “ornamental” or “decorative”.When he was under pressure from the Nazi regime, one critic interceded on his behalf, arguing that the Nazis should rethink their edicts since ornament art was part of an old German tradition. It was to no avail. And anyway an animated advertisement for Muratti with skiing and parading cigarettes had made Fischinger a name in Hollywood. Paramount organised for him and his films to emigrate, along with a pile of Karl Nierendorf ‘s non-objective canvases, a year before the exhibition Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) opened in Munich in 1937. The final assault on modernism, which began with the closure of the Bauhaus in 1933, ended with the vilifying parade of 650 artefacts by 112 artists. Works were condemned for their “barbarous methods of representation” as much as their immoral sullying of religion and preaching of political anarchy.With their references to Negro and Pacific art, Expressionist works “eradicated every trace of racial consciousness”. Worst of all, though, was “the art of total madness (abstraction and constructivism)”, and fourteen Kandinsky canvases, deemed “crazy at any price”, provided proof of this, even if two were hung sideways.

Oskar Fischinger

Muratti Greift Ein 1934

Colour, sound 35 mm film

Film stills

© Elfriede Fischinger Trust/courtesy Center for Visual Music

Oskar Fischinger

Muratti Greift Ein 1934

Colour, sound 35 mm film

Film stills

© Elfriede Fischinger Trust/courtesy Center for Visual Music

Fischinger found work in the USA, where commercial film production thrust itself on him in its most unadulterated form. Walt Disney was planning an animated feature illustrating several pieces of classical music and engaged the conductor Leopold Stokowski, who knew that Fischinger had been making animations pegged to music for some time. Study no. 8 (1931), for example, devised images for Paul Dukas’s The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, a scherzo Disney would later use in Fantasia. Unlike Disney, Fischinger did not illustrate Goethe’s story, but rather translated the textures and movements of the sounds into spurting and tumbling black-and-white shapes. In 1938–9 Fischinger was hired by the Disney studio as a “motion picture cartoon effects animator”, earning $60 a week. Having animated the sparkle of the blue fairy’s wand in Pinocchio, and thereby converted his abstract powers directly into Disney magic, he produced sketches and try-outs for Bach’s toccata and fugue section in Fantasia. In one major sequence, turquoise and green-grey waves were superimposed by a flow of geometric figures in browns, orangey-red and yellow oranges. His twenty seconds’ worth of film was worked over by Disney staff and the shapes made simpler, for the assumption was that only then would audiences accept them. Just one figure moved at any one time, and in the background floated clouds in a sky. The non-figurative forms were concretised, conjuring up real-world objects. While Fischinger thought he was utilising the insights of the colour theory he had studied, Disney objected to too extreme a palette and altered the colours. Fischinger’s deformed contribution was set among kitschy images derived from jabbing violin bows, ethereal cathedrals and doomy shafts, with the anchoring spectacle of the black-suited conductor who marshals all this energy. Fischinger quit the film in disgust. Clearly still smarting from his experience a decade later, he reflected on the state of cinema, attacking the usual “photographed surface realism-in-motion” that destroys “the deep and absolute creative force”:

Even the animated film today is on a very low artistic level. It is a mass product of factory proportions, and this, of course, cuts down the creative purity of the work of art. No sensible creative artist could create a sensible work of art if a staff of co-workers of all kinds each has his or her say in the final creation - producer, story director, story writer,music director, conductor, composer, sound men, gag men, effect men, layout men, background directors, animators, inbetweeners, inkers, cameramen, technicians, publicity directors, managers, box office managers and many others. They change the ideas, kill the ideas before they are born.

Fischinger’s remarks signal the end of an era of exchange between avant-garde art and mass culture. In 1932 the situation had been more hopeful. At a premiere of Fischinger’s Study no. 12 in Berlin, the critic Bernhard Diebold gave a speech entitled “The Future of Mickey Mouse”. If cinema was to be an art form, he argued, it needed animation, because that made possible a cinema that had broken free of a naturalistic template and conventional storylines. Animated film defied the inherited artistic genres, forging something new: “living paintings”,”musography”, “eye-music”, “optical poetry” and “the dance of ornaments”. For Diebold, Disney figures, with their elastic and rhythmic universe, had just as much pointed the way as had the “absolute films” of Fischinger, Hans Richter, Walter Ruttmann, Lotte Reiniger and others. All sorts of experimenting artists found that cartoons touched on many things that they too wished to explore: abstraction; forceful outlines; geometric forms and flatness; and the questioning of space, time and logic, that is to say, a consciousness of space that is not geographical but graphic and time as non-linear and convoluted. Animation was proposed as the medium to translate into movement Kandinsky’s restful points and dynamic lines in tension. When Rodchenko wrote in 1919 of the line that stands firm against pictorial expressivity, lines that reveal a new conception of the world in construction and not representation, he could have been describing cartoons’ flexible and cavalier attitude to representation. This inaugurated an extraordinary episode when Eisenstein could speak of his indebtedness to Disney, Adorno raved about Betty Boop, Vertov and Shklovsky imagined the future of film in cartoons, Oskar Fischinger could go to Hollywood and Siegfried Kracauer could be disappointed enough in 1941 to condemn Dumbo as a setback for the revolutionary movement. And Walter Benjamin could enthuse about Mickey Mouse, writing a defence of Disney’s utopian unmasking of social negativity and the rejection of the civilised bourgeois subject by this mouse-shaped figure of the collective dream.

In the 1920s Ruttmann, Richter and others threw away their canvases in favour of pictures that moved: multiple Mondrians a second. Once on this path they were drawn away from the art world and pulled further into the film world, away from abstraction into montage and staged actuality. Fischinger, despite or because of his encounter with the culture industry at its most intense, was perhaps more than the others committed to preserving film as art, that is to say, in Kandinskyesque terms, as pure form and colour, as a spiritual and emotional experience with the artist as prophet. In any case, he did not abandon painting and, in 1947, his animation Motion Painting no. 1 provided a document of the painting process. He laid Plexiglas sheets on top of each other to enable the generation of mutating shapes and styles. It is a seamless flow of action over eleven minutes, filmed by stop-motion. The artist is absent. The painting seems to paint itself. It echoed Fischinger’s first experiments in animation in the 1920s, when he built a device that cut slivers from swirled coloured waxes while a camera shutter, synchronised with the movement of the blade, recorded the patterns formed of the whorls and striations of wax. In projection the wax came to life in extraordinary ways, its frame-by-frame record flowing into continuous animation.

Motion Painting no. 1 had been commissioned by Baroness Hilla Rebay, who wanted a film synchronised to Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto no. 3. She hated the result and Fischinger’s Guggenheim connections were severed. Not long before, another of his supporters, the art dealer Galka Scheyer, had died. A specialist in what she called “The Blue Four”, Kandinsky, Klee, Jawlensky and Feininger, she had helped him since his first months in the USA. Fischinger never made another major film before his death in 1967. Perhaps the Kandinsky images mutilated by Mickey and Minnie Mouse were a symbol of his final stranding between two worlds.