During the Second World War I met and fell in love with a beautiful American nurse called Sylvia. We decided that we wouldn’t get married until people stopped shooting at us. Eventually we did, on 3 September 1945. Shortly thereafter, I went to America to visit her family, where I got to know her sister’s three children: Joan, Carol and Carl. They were a very close family, and they adored Sylvia.

When he was about eighteen, Carl came to visit us when we lived in a little village called Horton in Buckinghamshire. He was a very delightful, fascinating boy, and excellent company. I’m a great lover of the English countryside, so it was totally natural that I should want to introduce my newly discovered nephew to these pleasures. When we went to Salisbury it was a misty morning, and our first sight of the cathedral was its beautiful spire. It was a magical moment. We then took him to Stonehenge. I don’t think he had seen antiquity on such a scale before. The massive stone structures of Stonehenge and the soaring spire of the cathedral in virtually the same landscape made a profound impression on him. A short time after he returned to America he sent over what must be two of his earliest drawings, which I think are quite remarkable and still hang in my drawing room.

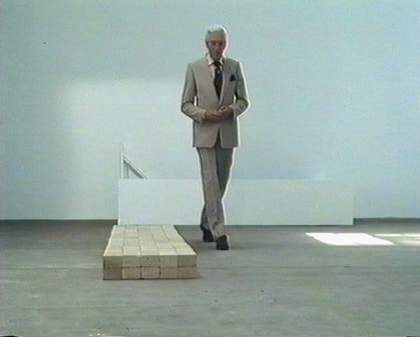

Raymond Baxter with Carl Andre’s Equivalent VIII in Upholding The Bricks, screened in 1991

© Courtesy Patrick Uden © Carl Andre/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2006

I got to know Carl’s family very well. His father was an amazing chap. Born in Sweden, he emigrated to the States as a child, but remained very Swedish. He was a naval designer – a specialist in doing the plumbing and wiring in the shipyard – and was extraordinarily skilful with his hands. He was a talented woodworker and had a workshop in his basement, which Carl would often visit. Carl’s grandfather had designed and built their house in Quincy, Massachusetts. It was a delightful place. I’m sure his grandfather’s skills as a stonemason, as well as those of his father, influenced the way Carl would later use materials in his own work. His father undoubtedly had a great influence on his life – to such an extent that he rebelled against it; at one time he deliberately looked wild, with his long beard and hair.

In 1967 I went on a business trip to New York. I knew that Carl had an exhibition, so we arranged to meet at his gallery. I remember walking into this huge, brilliantly lit and apparently empty room. We said hello, chatted, and then after a while I said: ‘Okay Carl, so where’s the work?’ And he said: ‘Uncle, sir, you are standing on it.’ He threw back his head and laughed in sheer delight.

On our next visit to the States we went to the opening of a big outdoor sculpture of his called Stone Field Sculpture 1977, up in Hartford, Connecticut. When we talked to him about it, he attributed much of that piece to his visit to Stonehenge. He was fascinated by henges and the significance of their juxtaposition in space.

When Carl exhibited the piece called Equivalent VIII (known as The Bricks) at Tate in 1976, it created huge controversy and criticism. I was outraged by this criticism, as was Carl, because it was ignorant, bigoted and cheap. I think it is impossible not to like his work. Subsequently, I got together with an old BBC colleague of mine, who had worked with me on Tomorrow’s World, and we made a programme in defence of his work. Carl was very reluctant to be in the programme, but I managed to persuade him that it was a good idea.

When my wife died in 1996 Carl was unable to come to the funeral, but he sent over a piece of Quincy granite for the memorial stone. It was a typically kind gesture of him to make. The stone now lies in Ewelme Churchyard, Oxfordshire, and I’m sure Sylvia is very pleased about that.