KARSTEN SCHUBERT When a museum rehangs its collection, who is it being done for?

KATHY HALBREICH It ultimately has to be done for your public, which ranges from a child who may have never been to a museum to a curator with specialised knowledge. But I also think any re-hang is a kind of exquisite and necessary luxury, as it forces a curator into an unusually intimate relationship with individual works as well as the whole, permitting private pleasures to dictate research for the public good.

MAX HOLLEIN I think you do a rehang mainly for yourself, as a diverse and infrequent audience does not necessarily understand or appreciate re-hangs. Also, I think you do it for the care of the works themselves. By re-installing you can refresh works, bringing them into play again – out of storage, for example. This can put them into a context that some other curators might have not considered.

KATHY HALBREICH I like the word refresh, because rehangs are about re-seeing, breaking down old ideas about how, and in what context, art should be seen. It’s both stimulating and clarifying either to create new or abandon old hierarchies, to disrupt preconceived notions of, say, beauty, or to fiddle with the drama of the space itself.

MAX HOLLEIN While we are used to the idea of rehanging in modern art institutions, in old master galleries it is a hotly debated process. In such places as the Louvre in Paris, the Kunsthistorisches in Vienna, or the Accademia in Venice, the works are hung according to an old formula based on chronology and regionalism. But if one can add some refreshing moments in there, I reckon the results can be astonishing.

Chantal Akerman

D’Est 1993/1995

Five-channel video piece

Installation view at the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis

© Collection Walker Art Center; Justin Smith Purchase Fund, 1995

KARSTEN SCHUBERT It seems that many art institutions and museums have recently been re-installing their collections. Since 2003 the Hirshhorn Museum has presented Gyroscope – the title name for the frequently changing non-chronological presentations of its modern and contemporary collection – while last year the Pompidou opened Big Bang, its thematic collection displays. Don’t you feel there’s a danger that some people may get a bit jaded about these changes?

MAX HOLLEIN I think what you’re implying is that there’s only one way to tell the story about a collection, but you have to accept that there are many different ways to tell the same story, and it ultimately remains the same truth.

KATHY HALBREICH People too often come to institutions looking for some kind of truth, and consequently they don’t necessarily arrive with as open or playful an attitude as they might. I would like to say to them: “What you see in these galleries is one story and only one way of looking. Imagine other stories - your story – here.” Our educational institutions don’t teach young people to interrogate other institutions enough.

MAX HOLLEIN Are we misusing our own resources by constantly mounting exhibitions rather than focusing on the collection? I think a more diligent process would be about reshaping the collection, rather than creating one special exhibition after the other. And I say this as a director of a kunsthalle that puts on nine shows a year!

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, art handlers moving Arthur Hughes’s La Belle Dame Sans Merci 1861–3

© National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

KARSTEN SCHUBERT But wouldn’t you say that the rehang is another form of exhibition?

MAX HOLLEIN An exhibition is supposed to test certain ideas; and if it’s good, then it should affect the presentation of your collection, not the other way around. So the sensitivity as well as the goals are different. But certainly you will need to use exhibition strategies when thinking about rearranging your collection.

KATHY HALBREICH I agree. At the Walker Art Center, we often find that doing research into the permanent collection is a good starting point for a show. For example, in 1997 we did an exhibition of Joseph Beuys’s multiples, a large collection of which we had recently acquired. What was terrific was that the curator, following in Beuys’s footsteps, designed the gallery as something of a hybrid – part classroom, part display area, part community library. However, the sad reality is that many of us don’t do more shows like this because they don’t sell as well. It’s very important for directors to fight for the funds to do such exhibitions, and to help curators to see that their careers will benefit from organising them.

KARSTEN SCHUBERT Kathy, you’ve just rehung the Walker Art Center. Certain pictures form the cornerstones of any museum collection – works that the audience expects to see. How do you deal with those that don’t fit into the rehang?

KATHY HALBREICH We accept that some people will miss things they have seen in the past, and we hope that others will be deeply moved by art they have never seen before. Sometimes we can’t show a famous work because it’s on loan, but sometimes singular works are not easily incorporated into a new hang. For example, Franz Marc’s The Large Blue Horse 1911 is a fabulous picture, but difficult to show because there are no other pictures of its time in the collection (a problem that many institutions share). However, we did do a special exhibition around it, and we will loan it to our sister institution, the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, for the opening of a new suite of galleries. Perhaps we’ll be able to arrange a long-term exchange with them. But we have to remember that there is more to galleries than painting. When we reopened, we used one huge gallery to display Chantal Akerman’s film and video installation D’Est, which we had commissioned several years earlier. Twenty-five paintings could have fitted in that gallery. So, as museums increasingly buy works in various media, we need to think about different ways of showing these acquisitions.

Art handlers hang Vermeer’s The Love Letter c.1669 at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Photo: Photograph: Paul Harris/courtesy The Age newspaper

KARSTEN SCHUBERT I think there is also something else happening. A traditional static narrative that one might find in a painting does not exist with film and video work. It has its own pace. So the museum, in some cases, can have the feel of a multiplex as you walk from one dark room to the next. How is that dealt with?

KATHY HALBREICH Well, for the Walker rehang, Richard Flood and Philippe Vergne, who were the lead curators on the reinstallation project, shaped a show within the whole called ‘Shadowland’. The idea was to integrate painting, sculpture and moving image material. It started beautifully with Beuys’s The Silence (which is five reels of Ingmar Bergman’s film of the same name), Richard Prince’s Untitled (living rooms) from 1977 and Jeff Wall’s Morning Cleaning, Mies van der Rohe Foundation, Barcelona 1999, suggesting our beginning was the end of modernism. Conceived as a visual promenade, the next suite of galleries featured artists such as Gerhard Richter and Kai Althoff, Robert Mapplethorpe and Catherine Opie, ending with Bruce Nauman, On Kawara and David Hammons. I was amazed to see how people lingered in these galleries, and you could sense they enjoyed making a connection between the different disciplines.

MAX HOLLEIN When you do a re-hang you can get a lot of criticism. You’re not doing a show, you’re working with a collection that is with you forever, so I think it’s well worth doing some dry runs. On one you might hit it right on the mark, and if some of it goes wrong, well it’s all part of the process.

KARSTEN SCHUBERT Maybe people’s anxiety has to do with museums as places of authority. I think audiences want them to be authoritative, but at the same time fully acknowledge the subjective nature of many curatorial choices. Perhaps, as curators, you should put up little health warnings at the entrance of the gallery saying: “This is not written in stone, we are trying this out and we are trying our best, and all alternative suggestions are welcome.”

KATHY HALBREICH Even though you might mean that as a joke, you’re right. And the audience can engage in this debate. For example, one of the students who participated in a film-making project undertaken by our teen arts council was interested in interpreting Jana Sterbak’s Meat Dress 1987. She found Jana’s telephone number, spoke to her, and talked about the dress in the film from her perspective as a young Asian-American woman. She asked us: “What does it mean to be in an all-white institution?” She possessed a sly but very sharp tongue, and, I’m happy to say, is making her way as an artist now. I think you have to welcome all of those questions into the institutions.

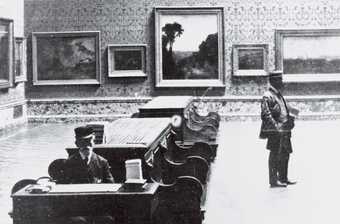

Tate works ready for storage in the North Duveen Gallery, Tate Britain 1939

© Courtesy Tate archive

KARSTEN SCHUBERT Tate Modern has rehung levels three and five with four hubs that embrace major historic moments as the central theme – ‘States of Flux: Cubism, Futurism, Vorticism’,’Material Gestures’, ‘Poetry and Dream: Surrealism and Beyond’ and ‘Idea and Object: Around Minimalism’. And around each it shows works that link to the theme. For example, with ‘Poetry and Dream’ there are such pairings as Cy Twombly and Joseph Beuys, and Cindy Sherman and Gillian Wearing. It seems the hubs provide strong starting points around which to weave related stories.

MAX HOLLEIN I agree, but that is not a recipe for just any institution. It obviously depends on the very special nature of your collection. What works with one collection does not necessarily work with another.

KATHY HALBREICH Even though I had some real problems with the first hanging, which flirted with the thematic rather than the chronological, it was extremely healthy for all of us in the field to be discussing its merits and pitfalls. However, what I missed most was some sense of the true curatorial heartbeat of Tate. In a strange way it was a very safe set of strategies, because, just as one sensed a more expansive understanding of a particular moment in time, one was whiplashed back into a more conventional view. And the lighting was truly devastating for a lot of the work. I think using chronology to shape the display can be both accessible and fascinating.

MAX HOLLEIN I think that an institution with a contemporary art collection has an easier display job than an old masters gallery. That said, some contemporary works resist re-hanging. Can you imagine Richard Serra’s Torqued Ellipses at the Bilbao Guggenheim being moved around? Having just become the director of the Städel Museum, while remaining director of the Schirn Kunsthalle, I am obviously now facing the issue of how to apply some of the thoughts and strategies that were first explored in modern museums with regard to collection re-hangings to old master paintings. The Städel has an extraordinary collection ranging from 1400 to the present day. In old master galleries you always have the same amount of wall space devoted to a painting, one after the other, a row of pictures. But if you hang, for example, a small Jan van Eyck by itself, away from others with much more space around it, you might get a sense of its quality as an icon that it had at that time. One could also play around with chronology, by speeding it up for instance. Certain rooms could suddenly break the chronology by, say, showing the development of portraiture from 1500 to 1800, while in the next room you come back to the time of 1550. Of course, how a work is mediated depends so much on the audience. Not everyone knows about the iconography or historical background of the old master paintings and what they represented. I see that there is a need to tell the history that surrounds them and give the visitor a key to understanding it. We should be very sensitive about that. Audiences in modern and contemporary museums seem to get the feeling that they have a closer connection with and understanding of the works on display than in old master galleries. This is in a sense very odd, since we must admit that in general it’s more complicated and complex to understand a Beuys than it is to understand a Raphael painting.

KATHY HALBREICH People often say that contemporary work is so political, but all that suggests to me is that we can no longer read the social, economic or political images of past painters. Art is and always has been political – artists have no choice but to be. I look at Renaissance paintings, and sometimes I don’t know what the iconography means, or what role the patrons played. It’s interesting that historical museums don’t feel they need to do that kind of explaining to their public.

KARSTEN SCHUBERT So without the information on a wall text, what are you actually giving them?

KATHY HALBREICH You’re giving them a formal beauty, which I think is just one critical component of a work of art. But don’t you think that young people are more able to entertain the ambiguity of contemporary work than their elders?

KARSTEN SCHUBERT Do you mean they are not as set in their ways as we are?

KATHY HALBREICH Yes.

KARSTEN SCHUBERT One of the things we haven’t talked about is that strange feeling you can get when you walk into a rehang of a museum that it looks like somebody has done the planning in his office with a slide projector, without any regard for the physical reality of the objects.

MAX HOLLEIN That’s something you encounter all the time with exhibitions. You just have to look at the paintings with frames and you will have a lot of surprises. The light and the real space can transform the initial concept of the curator. That’s not only an issue of collection installation; it’s an issue of any installation.

KATHY HALBREICH I think a curator can kill a work of art. So few people understand what Richard Flood used to call the mise en scène of a gallery. We are talking not just about the pace of an exhibition, but the use of light, the colour of the walls, the sound that your feet make on the floor, the overall tone of the room. We shouldn’t pretend that what we’re doing is scientific; it is just about getting the right “temperature”. This brings us back to Karsten’s point about the authority of an institution.

MAX HOLLEIN Where do you think that awareness of a museum’s authority comes from? It’s one of the few areas where that authority still seems intact, and we should make every effort to keep it that way and be true to that idea. You can still be accepted or not accepted as an authority, but nevertheless you should argue from that position, which in essence means you have to be clear and succinct with your arguments, and not vague. People expect from a museum a clear viewpoint, a statement – even if it is only the basis for their own discussion and maybe, at the end, disagreement with the authority.

KATHY HALBREICH In an ideal world, people would identify cultural institutions as places where people and ideas converge, where debate is encouraged, where one is free to have one’s own thoughts and opinions. But what is missing from many institutions is the permission to disagree. When someone says to me “I don’t like it”, I say: “Okay, let’s start from the beginning here. ‘Like’ is great for above your sofa. It’s not a good institutional mission or criterion. Let’s talk about what you don’t like, and why.” Often that is a much more interesting conversation. I’m sure we three could come up with several works of art that we dislike intensely, but which we agree should be acquired. Collecting isn’t just about personal taste (at least as it applies to institutional policy). But we don’t often make that confession public. Just imagine the conversations that we could have.