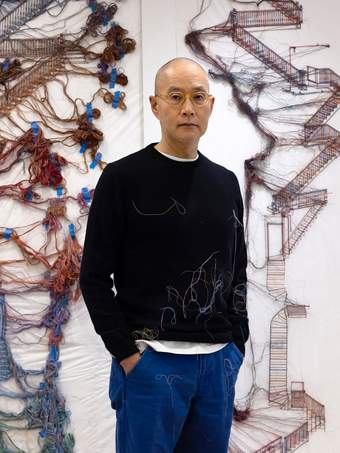

Do Ho Suh in his studio, London, 2025. Photo by Gautier Deblonde

© Gautier Deblonde. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025

Janice Kerbel Do Ho, our connection goes back to 1993, when we both attended the summer residency at Skowhegan School of Painting, Maine. I wanted to start with the birthday cakes of paint you made there. In my experience, cakes always relate to memories of home.

Do Ho Suh I can’t believe you remember those! I very rarely, if ever, show that body of work. I was coming from a background in traditional painting in Korea – I was interested in the slippage between meaning and form. So, the birthday cakes were kind of an experiment: when you saw one, you knew it was not a real birthday cake, but a lookalike made from acrylic paint. They were so inviting visually, but if they’d been too successful as sculptures then the beholder would have wanted to consume them. Then again, the three-dimensionality confused the ability to consume them as just an image.

It’s interesting that you associated the birthday cakes with the idea of home, though, because it was that process of questioning that led to the idea of transporting architectural space to other places.

JK I read something recently by the critic James Wood: ‘I couldn’t go back home because I wouldn’t know how to anymore.’ I’ve been thinking about the idea of homecoming, which is part of our cultural and literary hardwiring. The houses you make – your fabric architectures, your rubbing works – aren’t exactly replicas of homes, but they embody both a departure from home and a sense of return.

DHS Yes, there’s sort of a two-directional thing going on. When I was living in Seoul, the concept of home didn’t exist: it only started to exist when I left home and went elsewhere. That was when I started to wonder where home existed. How much of my former space did I carry into my current space? What was home before then? There’s a notion in sociology that I’ve always found helpful, ‘marginal man’, which describes the position of people who are displaced or who are immigrants in a society, who cannot be fully part of the mainstream, yet at the same time, no longer belong to where they came from.

I should also say that when I talk about feeling homeless myself, I don’t mean it literally. I’m mindful that we are seeing an ever-deepening global crisis of forced displacement, and I want to be clear that my experience of movement was not forced but voluntary.

Do Ho Suh Rubbing/Loving: Apartment A, 348 West 22nd Street, New York, NY 10011, USA 2014 Coloured pencil on paper

© Do Ho Suh, courtesy Lehmann Maupin Gallery, New York, London and Seoul and Victoria Miro. Private Collection. Photo: Christopher Payne

JK Your rubbing works seem to be reaching toward something that is outside of language, beyond memory. They exist somewhere between sculpture, drawing and print. Whenever I go back to my parents’ house, I am always surprised how something as simple as touching a table in the front hall instantly connects me with what is past.

DHS And that touch triggers all sorts of memories. It’s actually the opposite of what happens with my rubbing pieces, where I cover entire surfaces with paper, so I become blind to colour and detail. The instant I’ve masked that surface, I can no longer remember what exactly is behind it. It’s like a form of dementia: I’m aware that I know what’s under the paper, but I don’t have access to the memory. And when I start rubbing, things rush back. When I was rubbing my old apartment in New York, I found two holes in the wall that I’d completely forgotten existed. But as soon as they started to emerge, I knew exactly what they were and the fact I’d once made them for a coat rack so I could hang more clothes. Then I remembered even more – the journey from my apartment to Bed Bath & Beyond on Sixth Avenue and back, the temperature that day, the light. That made me wonder about memory’s mechanisms – why did these thoughts resurface as I was rubbing? When I eventually had the opportunity to rub the entire brownstone that housed my apartment, I thought continually about that, because the landlord, Arthur, who I’d become close friends with, had died with dementia.

JK Can you describe the rubbing process?

DHS I have to use a very precise pressure throughout the entire rubbing. Too light and you cannot depict the texture of what’s beneath the paper. Press too hard, you obliterate that texture. It has to be a certain pressure, and also very constant. It’s a bit erotic, actually. More than a bit! It’s like caressing a lover’s body, staying very attentive and sensitive to their reaction.

It’s such a simple gesture, but when you’re dealing with a much larger space it ends up being an intensive process. By the end of a project, I have consumed the space that I’ve rubbed or measured and turned it into a Rubbing/Loving or fabric architecture work. That’s when I feel I can leave that space behind, that I can’t do it again, because I am completely exhausted.

I think it’s the same with how I make drawings. In Eastern painting, each mark is the equivalent of a breath. The stroke needs to contain life and it can’t be withdrawn. You lay a mark on the paper and that’s it. It requires a very physical level of focus – if I’m drawing faces, for instance, unless I really concentrate, my hand moves automatically and I end up repeating the same sort of shape.

Do Ho Suh Rubbing/Loving: Apartment A, 34 8 West 22nd Street, Ne w York, NY 10011, USA 2014 (detail) Coloured pencil on paper

© Do Ho Suh, courtesy Lehmann Maupin Gallery, New York, London and Seoul and Victoria Miro. Private Collection. Photo: Christopher Payne

JK You also work collectively with a lot of people to produce many of your works.

DHS I can’t make art without other people’s help. My current team in London includes several professional architects and a designer with a fashion background. We have a lot of group discussions, and my ideas evolve as I’m explaining them to my team, and in turn I get new ideas from their responses.

JK I think a lot about ideas around hospitality and reciprocity, and I wonder if the studio model you’re describing is like that. Everybody has to feel connected to the process in order for a work – and your collaborators – to evolve. I am wondering if the studio, or the work itself, starts to feel like a home?

DHS Yes. At the same time, I’m fundamentally an extremely introverted person. I do need separation – I cannot really function or think if I don’t have my own quiet space and time.

JK I guess it demands both. Some things happen in the studio practically, materially, while other things happen when you’re alone.

DHS One of the reasons I didn’t pursue painting was that you have to make constant, spontaneous decisions, and I wasn’t good at that. My attitude with my work is that I often try to defer those decisions and not to define things too much.

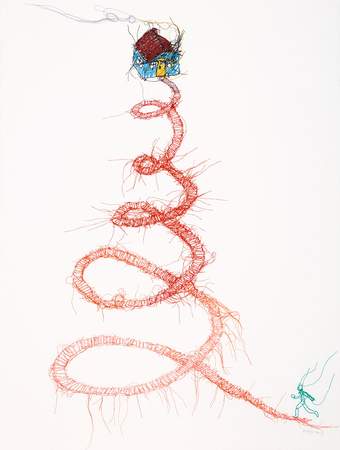

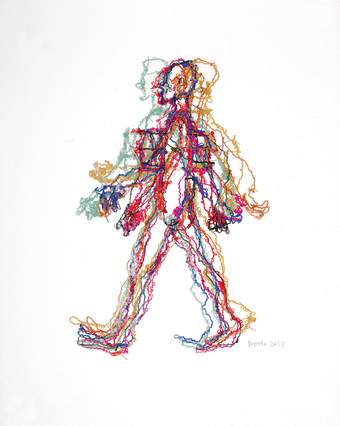

I guess that the thread drawings allow me to accept accidents into my more programmatic work. When the STPI team – a group I work with in Singapore – suggested using thread to make my drawings, I couldn’t immediately see that connection but then I saw what they did. The thread has the same thickness and quality of line as my pen drawings, so it’s a close translation. There are decisions mad e along the way in the thread drawings – steps I figure out in advance, so it’s still quite process-oriented – but the making is temporal and spontaneous, like ink painting.

Do Ho Suh Going Home 2013 Thread embedded in paper 61 × 45.7 cm

© Do Ho Suh, courtesy Lehmann Maupin Gallery, New York, London and Seoul and Victoria Miro. Private Collection. Photo: Christopher Payne

JK The major difference, it seems to me, is that the drawn line doesn’t want to do anything in particular – it’s just what you do with it – whereas the thread has a certain materiality that dictates what it will and will not do.

DHS It’s like catching an eel in a river – I literally have to use water to control or at least try to control it. The thread has its own life, its own tension, and it doesn’t want to move as I want it. That can be frustrating, but it’s exciting, too – I like the spontaneity of the sensation. It’s immediate, or present. Because actually, when you’re drawing, there’s a kind of blindness that occurs when you’re making a mark on the paper. This is something that the philosopher Jacques Derrida talks about: when your pencil nib touches the paper, it covers the mark that you are making, so you’re blind to the mark on the paper at the moment of its creation, meaning the mark is always in the past.

In the same way, we think of ourselves as living in the present, but in reality we’re living in the past, and therefore we can probably talk about the future, too. We believe we’re controlling time and this present moment, but we’re not. Even now, when you’re formulating a thought, it’s worth thinking about how much is new: 99 per cent is from memory. I think we’re bound to always go back to the past, to the same areas of interest, the same kinds of thoughts.

Do Ho Suh Myselves 2013 Thread embedded in paper 35.6 × 27.9 cm

© Do Ho Suh, courtesy Lehmann Maupin Gallery, New York, London and Seoul and Victoria Miro. Private Collection. Photo: Hyunsoo Kim

JK You recently exhibited your sketchbooks for the first time, and to me that feels like another aspect of this two-directional flow, this deliberate collapsing of past and present.

DHS Those drawings were never meant to be shown – they were just part of my journal, so I had no intentions for them. I just drew and moved on. Mostly they’re technical, trying to resolve details of my sculpture. They’re black and white line drawings, made with the same pens and in the same sketchbooks I’ve used since I was a student. And then suddenly they became the basis for the thread drawings.

JK The thread introduces difference while the line is always the same… That makes me think of something the poet Elizabeth Bishop said about letters: ‘Once detached from the moment and circumstance of composition, there is something impersonal and strange about any piece of correspondence. On that level, every letter is a letter found on the street.’ I think something similar applies to drawings: when they’re in the sketchbook, they’re part of a whole world – but rip the page out and it suddenly becomes its own thing.

DHS It’s interesting that you relate it to letters, to words and language. When you look at a sentence in English, I think you have an idea of what it is before it is formed into words. There’s something similar going on with these drawings: they are not abstract, but a mix of the recognisable and the imaginative or speculative. There’ll be a realistic figure, but it will be situated in this unrealistic realm. There’s a rawness to the drawings, a directness and an urgency, because they’re based on fundamental questions about our existence, but I haven’t yet formed a sentence to describe the image.

As visual artists we deal with visual signs and symbols, but I’m also interested in semiotics. I took courses in linguistics when I first arrived in the US, and I realised that the domain of language is inseparable from visual art. That made me really think about transparency and opacity, both in language and the visual arts, at a time when I was having difficulty clearly explaining my work in English. My frustration with the language barrier allowed me to think more about the function or purpose of language in conveying the meaning of the artwork, and that led me to decide to make my work as clear as possible so that I wouldn’t really need to talk about it. Subconsciously, I think I was also trying to remove my fingerprints, which in turn relates to the collaborative nature of my practice now – using a robot to create drawings, or making work with a lot of people, even though I’m not that social a person.

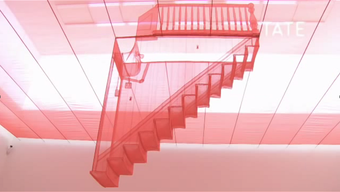

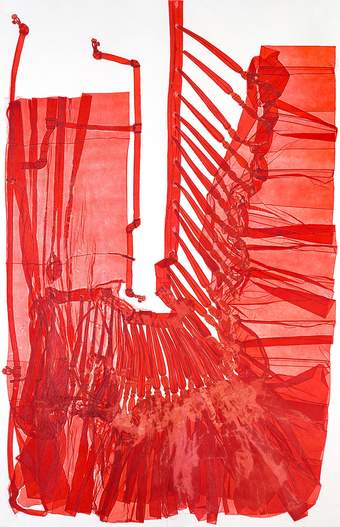

Do Ho Suh Staircase 2016 Gelatine tissue and thread embedded in paper 355 × 229 cm

© Do Ho Suh, courtesy Lehmann Maupin Gallery, New York, London and Seoul and Victoria Miro. Private Collection

JK What are your thoughts on working in the context of the museum as opposed to working outside of it?

DHS The museum as we know it is a relatively recent invention, a product of modernity, and has all the attendant problems of modernity. Because of that, it’s impossible for me to see the museum as a purely physical space – I’m always considering the context around it. And within it, too, which is why I began to question the plinth.

If you go to the Korean gallery of a Western encyclopaedic museum, you’ll see a statue of Buddha made in 400 BC right next to an 18th-century ceramic bowl that was probably used for drinks at the pub. They’re from completely different times and contexts, yet they’re both inside a case, on a pedestal, juxtaposed, made equivalent. I have a huge problem with that. That’s why my freestanding sculptures touch the floor. At Tate, we’re taking that further by showing a film of a monument – Public Figures – actually moving, to challenge the static nature of the traditional monument.

In terms of the museum – I chose fabric for the architectural pieces because the translucency means that you can bring the surrounding space into the piece, blurring the boundary between the artwork and visitors’ bodies. I want visitors to see the architecture of the museum through my work – that it’s not just this white space for art. If you’re inside of a fabric architecture piece, you’re actually part of the piece: you activate it.

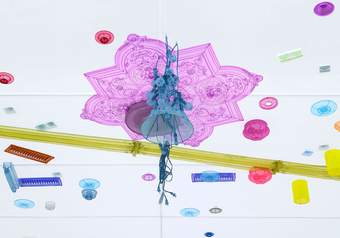

Do Ho Suh Perfect Home: London , Horsham, Ne w York, Berlin , Providence, Seoul 2024 (detail) Polyester fabric and stainless steel 455 × 575 × 1237 cm

Courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Seoul and London. Photo: Jeon Taeg Su © Do Ho Suh, courtesy Lehmann Maupin Gallery, New York, London and Seoul and Victoria Miro. Courtesy the artist, Lehmann Maupin New York, Seoul and London. Creation supported by Genesis. Photo: Jeon Taeg Su

JK At the same time as doing everything they are meant to do in terms of architecture and detail, the fact the homes are made of fabric renders them totally dysfunctional. They wouldn’t keep you dry or warm, for instance, and so they remind us that to have a home is also to be vulnerable, to have something that can be taken away from you.

DHS I think once you leave your first home, a perpetual sense of displacement and vulnerability sets in, even within the solid walls that protect you physically. The fabric architecture obviously amplifies that feeling of vulnerability. For instance, my old apartment in New York was a half-basement, streetside studio, with two big bay windows and my bed was right next to one of them, meaning I could hear everything from the street. There were metal bars on the windows for security, but sometimes I dreamt that people were looking in my window – hundreds of them. Sometimes within the dream they got into my room through the window, and then there would be hundreds of people inside a 400-square-foot apartment.

I think that’s also related to memory. At least in my mind, things from the past overlap with the space that I’ m occupying right now. My London apartment constantly reminds me of spaces from the past. Physically I may have left New York, but I never left New York. I’ve moved around so much in my life that the notion of home has become very complicated and cumulative. Although again, I want to stress that reflecting on voluntary movement is a privilege.

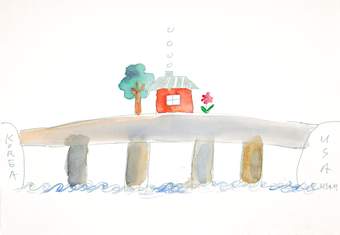

Do Ho Suh A Perfect Home 1999 Ink and watercolour on paper 25.1 × 35.4 cm

© Do Ho Suh, courtesy Lehmann Maupin Gallery, New York, London and Seoul and Victoria Miro. Private Collection. Photo: Hyunsoo Kim

JK There is a sense of accumulation in your more recent works. It’s as if the most recent memory is no longer the one that has to be prioritised – it’s like you’re asking what one memory is in relation to all the others. The timeline gets confused. In Perfect Home: London, Horsham, New York, Berlin, Providence, Seoul, you’re no longer working with the whole but with fragments, bringing elements together in such a way that the attachment to the real is fractured.

DHS For a long time, my thinking about time and space was really linear. I was trying to find the ‘perfect home’, a search I’d been carrying out for 30 years without ever finding it – or rather, discovering along the way that there is no one perfect home, but many different versions. When I began making Perfect Home, I realised it was impossible to think linearly about those things and that if I wanted to get closer to the notion of the perfect home, I would have to embrace an element of chance.

So, although every artefact in Perfect Home comes from an actual space and has been measured, modelled and stitched, they are arranged according to a computerised process, almost like the I Ching, where each actual outcome is just one of a million different combinations. I wouldn’t say it’s arrived at entirely by chance – I had to set the rules for the selection process and choose a certain combination from thousands of options, so there is some subjectivity involved, but only a little. What you get then is 30 different rooms superimposed on each other, 30 sets of objects all converging, sometimes losing their shape where they blur together.

Do Ho Suh Nest/s 2024 Polyester fabric and stainless steel 410.1 × 375.4 × 2148.7 cm

© Do Ho Suh, courtesy Lehmann Maupin Gallery, New York, London and Seoul and Victoria Miro. Courtesy the artist, Lehmann Maupin New York, Seoul and London. Creation supported by Genesis. Photo: Jeon Taeg Su

JK It’s kind of like a hybrid memory. This seems especially apt at a moment when to have a home at all begins to feel like both a luxury and a privilege.

DHS Absolutely. Today I would say that I doubt the existence of a perfect home, but I think I’m still on that quest for it, the perfect world. The Bridge Project started out as another attempt to find the perfect home. Currently, there are three different cities in my life that I call home – London, New York and Seoul – and if you triangulate the place that’s equidistant from all three, it’s right next to the North Pole. In trying to find the site of my perfect home, I end up in the most hostile place in the world. How am I to get there? I would need a bridge. One question follows another: How am I going to handle all these extreme climates? What would I eat? Whose waters and land would the bridge infringe on? What would it destroy? How would I overcome the violence and bureaucracy of borders? Wouldn’t I be so isolated that any notion of perfection would be rendered obsolete? It’s more epic than I originally intended. Again, I just followed this thread of thought and this is how it turned out. I guess the perfect home is a much broader, more complex idea than I’d originally thought. It’s not a small, cute house in a field. It’s not something that can be easily imagined.

TATE MODERN

The Genesis Exhibition: Do Ho Suh: Walk the House, 1 May – 19 October.

Janice Kerbel is an artist who lives in London .

In partnership with Genesis. Supported by The Genesis Exhibition: Do Ho Suh Supporters Circle and Tate Members. Co-curate d by Nabila Abdel Nabi, Senior Curator, International Art, (Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational) and Dina Akhmadeeva, Assistant Curator, International Art, Tate Modern. The creation and repurposing of artworks in the exhibition has been made possible with the generous support of Genesis.