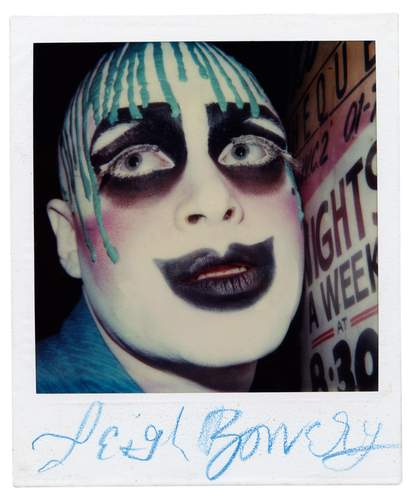

Peter Ashworth

at home with Leigh Bowery 1994

© Peter Ashworth

Caryn Franklin

Back in the mid-1980s, the BBC's prime-time fashion programme, The Clothes Show, drew a very large audience, peaking with UK weekly viewers of 13 million every Sunday evening. I was a co-presenter of this show, alongside my position as co-editor of post-punk style bible i-D magazine. I saw it as my role to recruit some counter-cultural colour and charisma to the trad TV show format, so I regularly reached out to a variety of creatives.

Leigh Bowery was one such memorable guest. A clubland friend, he and I were filmed sitting down to tea in the Harrods Tea Rooms. He was a big man, huge in chunky heels, and having effortlessly gained everyone’s full attention upon arrival, he treated diners to an impromptu catwalk show. Such was his effect that, unsurprisingly, this is one of the few surviving snippets of footage from the series that spanned 12 years.

Completely unabashed, he joined me at the table. ‘I couldn’t do this anywhere else but in London,’ he said, positioning his lavish body on a gilt chair while I poured Earl Grey. He was covered in sequins, florals and colour. The look included a balaclava-style face mask, theatrical eye makeup, gloves and thick tights over his ample legs. But he was not referring to the garments he wore, or the spectacle he presented. He was instead referencing his relationship with his body and his preoccupation with unapologetic transformation. He was his own private party, but more than that, he was a beacon of authenticity.

To anyone belonging to Leigh’s world, this would have seemed unremarkable. Many of us had normalised a raw signalling of our coded, or overt, identity politics through non-conformist attire. In a pre-mobile phone digital desert, one needed a megaphone. Appearance was our analogue social networking. Fetish, drag, cross-dressing, surrealism, or appearing draped in one’s latest art project – these were conversations that would be networked IRL, not via URLs.

Caryn Franklin has tea with Leigh Bowery at the Harrods Tea Rooms during an episode of The Clothes Show broadcast on BBC One in 1988

BBC © copyright content reproduced courtesy of the British Broadcasting Corporation. All rights reserved

Caryn Franklin has tea with Leigh Bowery at the Harrods Tea Rooms during an episode of The Clothes Show broadcast on BBC One in 1988

BBC © copyright content reproduced courtesy of the British Broadcasting Corporation. All rights reserved

Leigh epitomises an era for those of us who enjoyed an existence in opposition to social expectations and technical limitations. In a silent performance of the self, our clothes did our speaking for us. A weekly nocturnal commune, with a familiar congregation of nascent creatives, fluid and queer humans and oddball dressers, happened every Thursday at Leigh's club night Taboo. Even just getting ready for it was exhilarating and vital.

Of course, Leigh’s trajectory would outgrow pedestrian club promotion. He made clothes not just for himself but also established the label Spend, Spend, Spend with Rachel Auburn, catering to the club scene. These clothes were both striking and kitsch, but Leigh, seeking an even more flamboyant and spontaneous outlet for both costume and performance, was soon drawn to the international stage. The Michael Clark Company was a collaboration that would last almost a decade. Clark, a gifted avant-garde dance artist and choreographer, combined precision ballet with irreverence and tawdry glamour. Leigh starred in various get ups, cavorting with purposeful impropriety.

There followed numerous and wide-ranging public appearances – a one-man installation at a major gallery, cutting-edge or shocking performances (depending on your position on enemas), a pop group called Minty, commercials for brands and, of course, front cover portraiture for magazines. Every transformation was a provocative manifestation of this man’s compulsion to self-fashion. Yet, in an unorthodox twist, and shortly before his untimely death in 1994, some of the most famous depictions we have of Leigh are by the artist Lucien Freud, which exhibit his six-foot-three-inch, 17-stone physique completely naked.

Leigh Bowery: an icon of uninhibited individuality.

Caryn Franklin MBE is a fashion commentator and author. She was fashion editor and co-editor of i-D magazine in the 1980s and long-time presenter of BBC Television’s The Clothes Show.

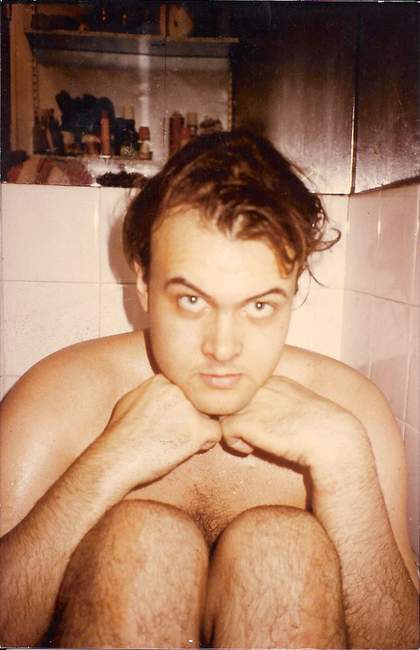

Leigh in the bath at Farrell House, Stepney Green, London, c.1980

Photo by Bronwyn Bowery-Ireland

Courtesy Bronwyn Bowery-Ireland

Bronwyn Bowery-Ireland

Leigh was the kind of older brother who believed he had to protect you and torment you at the same time. He relished both. He also had to be the centre of attention and he had to win.

We grew up in a very religious family in Sunshine, Melbourne, with parents that loved us but whose love was conflicted by the social pressures of the time. They didn’t understand Leigh, but in a strange way they were mesmerised by his self-assurance. As siblings, Leigh and I learnt to look out for each other. We spent all our holidays in the countryside – swimming, walking and creating adventures. At home, we would entertain ourselves through music: Leigh played the piano and I sang. We loved films and comedy too. We wanted to know about every new artist and what was going on in pop culture. Even from a young age, Leigh was fascinated with creating garments. He would spend a day knitting an entire outfit before proudly wearing it through the streets of our hometown.

Growing up in Australia had a profound impact on Leigh. In a recent BBC radio interview, Nick Cave, a fellow Australian, beautifully articulated a sense of the period in which we grew up, when certain troublemakers, or ‘social irritants’ – like Barry Humphries, who satirised a particular Australian-ness through creating an alter ego – were anarchic in their attitude and performance. ‘It was these people that taught me about not just the need to push against things, but the great pleasure in doing that... We found some weird power in separating ourselves from everybody else.’

For Leigh, the tragedies and challenges in his life were radical engines for his creativity. Leigh was courageous, outrageous and contagious. You just wanted to be with him.

Bronwyn Bowery-Ireland is Leigh’s only sibling. She has lived in Shanghai and Hong Kong, and now lives in Cardiff, Wales. She has two sons and is the CEO of a management consulting firm and is currently pursuing a doctorate degree in the UK.

Alex Gerry

Leigh Bowery at Taboo, London, 1986

© Alex Gerry

Alex Gerry

My first encounter with Leigh took place very early on, shortly after his first landing on planet Blighty. We were at Cha Cha, a happening weekly club night located at the back of Heaven, the nightclub beneath Charing Cross’s arches. Little did I know he’d already gone up to Scarlett Cannon, the night’s stunning co-promoter (who obviously didn’t know him from Adam), to ask if she could introduce him to some ‘influential’ people as he didn’t know a soul. He was always a cheeky sausage! He looked a bit gauche to me, but was resolutely charming and well-spoken. He told me he was staying in a bedsit in West London and had a job flipping burgers at Burger King, which threw me a bit. Still, I remember thinking he was someone who would be going places in clubland very soon.

Well, ‘going places’ would be the understatement of the year. In no time at all, he'd managed to meet and befriend virtually everyone who was anyone on the scene. He soon moved into a Stepney Green council tower block (where he would stay until his passing) with his partner-cum-muse Trojan, who had a huge influence on him. I lived within walking distance of his flat at the time, so one day I went to interview him for the Evening Standard and had a photographer take shots of us posing in his living room in front of his notorious Star Trek wallpaper.

Leigh soon became a fully-fledged designer, spending a huge amount of time creating his outfits with unprecedented attention to detail and great style. He also ran a stall in Kensington Market with designer and DJ Rachel Auburn to bring home the bacon. Friends, the likes of Mr Pearl (the bustier and corset maker) and Nicola Rainbird (who he later married), helped him when he could no longer cope with the number of outfits being ordered. He’d just started co-promoting and hosting his club night Taboo, which had proved time-consuming enough. This would also explain why he soon gave up designing for other people; he was only really interested in dressing himself and disliked dealing with the business side of the trade.

We travelled to Paris together a few times thanks to bookings from the legendary club Le Palace, where he performed and I DJ’d. I was close friends with the promoter, the much-missed Jean Claude Lagrèze (who was also a great photographer), and we were treated like royalty. At the time, I was given carte blanche to organise the French Kiss soirées out of London, often having to book flights and rooms for the performers at the hotel located right behind the club. I would have to escort the out-of-control pack from the airport to the club, ensuring, rather like a holiday rep, that none of them went astray. It was a barrel of laughs attempting to keep Leigh in check and stop him terrorising the regular hotel guests. They didn’t exactly relish bumping into him in the lobby or having to share a lift with him in the middle of the night! DJ Magazine also used to send me to New York for the annual Wigstock drag festival, a sensational event held in Tompkins Square Park that I covered a few years running, so I hooked up with Leigh whenever he was there.

Performing with dancer and choreographer Michael Clark at Sadler’s Wells and posing nude for Lucian Freud took pride of place on Leigh’s CV. However, his true calling was to appear, whenever he was out, as an ever-changing, outlandish, living art piece. Needless to say, he found his ideal arena in London’s clubland.

Alex Gerry is a nightlife and music photojournalist based in London. Since the late 1980s, he has contributed to numerous publications, including the Evening Standard, i-D, Dazed and Mojo.

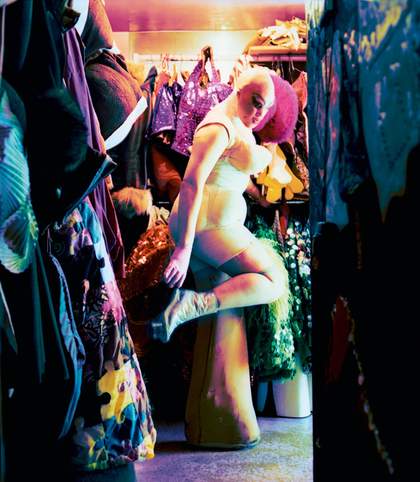

Peter Paul Hartnett

Taboo, Maximus, Leicester Square, London, 1985-1986

All © Peter Paul Hartnett / Camera Press

Princess Julia

In 1979, I did the coat check at the Blitz club, the spiritual home of the New Romantics. So when, some six years later, it was suggested that I might like to do a stint of coat checking at Leigh Bowery’s club night Taboo with my friend, the DJ Malcolm Duffy, I thought: why not I’d known Leigh for a few years, I went to Taboo most weeks, and Malcolm was an absolute scream. As I predicted, it was a lot of fun.

The luxury cloakroom was situated at the bottom of the entrance stairwell and was quite vast. Alas, my tenure was short-lived, as one week a Katharine Hamnett coat went missing. (I hasten to add that, on this particular night, Malcolm and I had dropped a tab of acid, so our problem-solving skills were somewhat dampened.) Malcolm and I were in hysterics, giggling and camping it up, blaming ‘the horse lady’. Who she was, I still have no idea.

My memories of times at Taboo are always of much hilarity. There was a real craziness, a real energy, which I always put down to Halley’s Comet – that, and the amount of drugs people were taking. Like the night Jeffrey Hinton decided to DJ with the slipmat instead of an actual record. Of course, people kept on dancing to the white noise of a needle on rotating felt. Leigh, in a panic, came running over to ask if I could tell Jeffrey to put on the next track. I rushed over to the elevated booth at the top of the sunken dance floor shouting: ‘Jeffrey, Jeffrey, what’s going on?’ He was oblivious to the grating sound and instead asked me to make him a cup of tea. Eventually, Jeffrey realised he wasn’t actually playing any music and casually lifted the needle to line up the next track, which came on to rapturous laughter and applause. Leigh liked to have a certain degree of drama going on; Taboo was a catalyst for that all to explode.

Princess Julia is a DJ, artist, model and writer.

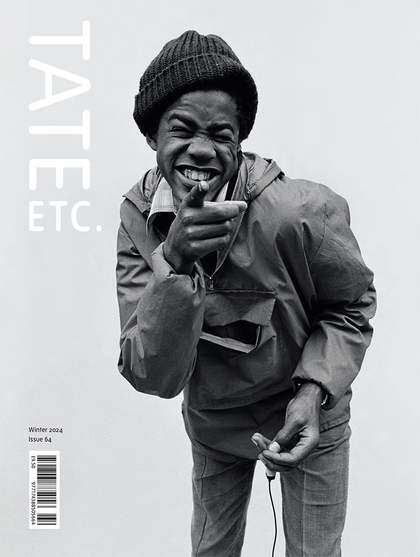

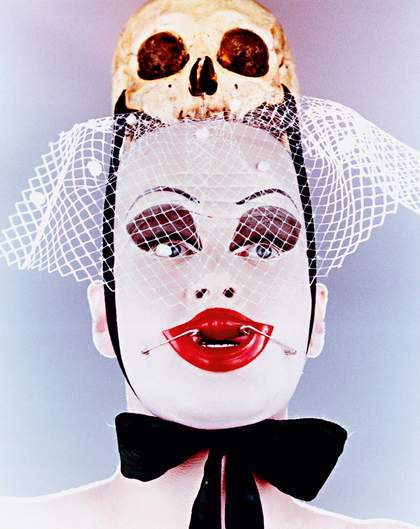

Nick Knight

Leigh Bowery, Yellow 1987

© Nick Knight

Nick Knight

Leigh Bowery, Skull 1992

© Nick Knight

Nick Knight

London in the mid-1980s felt like a smaller, more coherent scene, where everybody knew everybody. You'd hear about new people just through taking portraits. When I first worked with Leigh, as part of a series of 100 portraits for the fifth anniversary issue of i-D magazine in 1985, I couldn’t believe that I hadn’t already met him. I’d been told he was amazing and that I needed to photograph him.

When he came to the studio, I thought he was extraordinary looking. For a start, he was physically a lot bigger than anybody around him. In his shoes, he was probably touching the six-foot-six-inch mark and he was, of course, very flamboyant. He was quite a presence. But then, he was also disarmingly polite and gentle, speaking with softness and humour in a sort of 1940s/1950s BBC kind of way. He was a huge character, but you never felt that he was difficult or diva-ish.

I fell in love with him pretty much straight away, in an artistic sense. It was so clear that he was a living work of art: the way he painted and dressed himself was exquisitely fine-tuned. The range of colours and the semiotics of his clothes were so powerful but also so delicate. As a young art student, I had buried my nose in all manner of books about the cabaret scenes in Berlin during the Weimar Republic, and the wonderful characters from the 1930s when surrealism and transgression was raging across Europe. And then, all of a sudden, here it was right in front of me. Leigh played on all those wonderful aspects of crossing society’s boundaries and norms. There were already a lot of flamboyant characters on the scene – we’d just come out of the period of the New Romantics and Blitz Kid years of the early 1980s – but Leigh took it to a stratospheric level.

I probably photographed Leigh around ten times. Every time I did, I was a bit stuck as to what the hell to add, because it was all already there. Normally when I’m photographing somebody, I try to invent an image that takes reality a bit further. But with Leigh you really couldn’t do that; you had to sit back and just take a picture. What are you going to add to a man who’s already wearing a toilet on his head and shoes with nine-inch platforms? It was the same with nearly all of his outfits, whether it was the pig masks, the ten pairs of glasses, or the skull on top of his head. Leigh was transgressive in everything he did. The times I worked with him always stood out, because he was like nothing else in the world.

Nick Knight is an imagemaker and the director of SHOWStudio.

Leigh Bowery and Fat Gill as Miss Fuckit at the seventh Alternative Miss World competition, 1986. Photo by Robyn Beeche

© Robyn Beeche Foundation

Andrew Logan

I first met Leigh in the early 1980s at Michael and Gerlinde Costiff's flat in Chelsea. He was dressed as a blue Krishna, and Leigh's partner, the amazing Trojan, was painted green. It was a charming sight. They were both very quiet and sat in the corner, but we stayed in touch. London felt smaller then, so you’d bump into each other.

The first time Leigh appeared on stage was at the 1985 Alternative Miss World, 13 years after we launched in 1972. Based on Crufts dog show, the event was about transformation. Everyone came – the rich, the poor, the fat, the thin, the old, the young – it was open to the whole world. That year it took place at the Brixton Academy and adopted ‘water’ as its theme. Leigh wore a very distinctive look: he dressed as a cowgirl on rollerskates, trailing a supermarket trolley with toy guns firing as he careered across the stage. He didn’t win, but it gave him the confidence to go on. He saw the reaction and off he went.

His next Alternative Miss World appearance was the following year, when the theme was ‘earth’. This time his costume was more elaborate. He appeared with Fat Gill: she naked, and Leigh with exaggerated black lipstick and layers of white fabric, like a flower.

He was larger than life off stage too. One time, after my great friend Divine had performed on top of a Thames cruiser for Gay Pride, Leigh appeared, curtsied and then rolled down the stairs. Leigh was always full of surprises and took transformation to new heights.

Andrew Logan is a sculptor and the founder of Alternative Miss World, a surreal art event for all-round family entertainment.

The morning after the night before, New York, 1984. Photo by Sue Tilley.

Courtesy Sue Tilley

Sue Tilley

I met Leigh in 1982 at the Cha Cha Club and we soon became very good friends. I had always dreamt of going to New York as it seemed like the most glamorous and exciting place on Earth and, in 1984, Leigh made my dream come true. He had been asked to take part in a fashion show at the Limelight club in Manhattan. I was so excited when he asked me to go with him. When we arrived in New York, it was just as I’d imagined: manic, dirty and full of old-fashioned diners and huge shops. I was especially thrilled by the steam funnels and adverts on the subway for the roach trap brand, Roach Motel, which read ‘Roaches check in, but they don’t check out!’

We had a wonderful time exploring the city and meeting up with all our friends, and once over our jetlag we were out clubbing every night. We went to Area nightclub where we drank vodka and cran-grape cocktails (which we had never had before), and ate some magic mushrooms that we got from ‘Dial-a-Drug’, a service that we couldn’t believe existed.

We got so drunk that we had to leave early and go back to the filmmaker Charles Atlas’s apartment, where we were staying. Leigh carried on prancing around to entertain Michael Clark and his boyfriend, Richard Habberley, but then suddenly rushed to the bathroom where he puked up an avalanche of bright-red vomit. We then collapsed on mattresses on the floor to sleep.

When I managed to open my eyes the next morning, Leigh was looming over me with most of his makeup from the night before smeared all over his face and his hair standing on end. Even in London, this was regular behaviour for me and Leigh (and most of our friends): drinking to excess, getting in a state, and laughing about it in the morning. I dashed into the bathroom to assess the mess, but it was perfectly clean. In my drunken state, I had managed to clear it all up without remembering. Neither of us ever touched cran-grape juice again.

Sue Tilley is an artist and a biographer of Leigh Bowery. She was cashier at the club night Taboo and a muse to Lucian Freud. Her biography, Leigh Bowery: The Life and Times of an Icon, is being republished by Thames & Hudson in February 2025.

Loveleigh take off! Leigh Bowery, Michael Clark and Les Child at Heathrow Airport, June 1987. Photo by Ellen van Schuylenburch

Courtesy Ellen van Schuylenburch

Ellen van Schuylenburch

The first full-length work in which Leigh featured as a core Michael Clark Company performer was Pure Pre-Scenes in 1987, delivering dialogue and song in an opening vignette for himself and Les Child. Every night's performance opened with Leigh variously greeting the audience ‘Right on Brighton’, ‘Buenos tardes Valladolid’, ‘Bona tarda Barcelona’, ‘Hello Leicester’, ‘Dobro veče Belgrade’. Ljubljana, Rome, Leeds, followed by a world tour.

The tireless touring schedule of departing, arriving, checking in at hotels, questing for food, sleeping, getting ready for the performance made us as one... except for the occasion when Leigh, Les and Michael decided to be outrageous and catwalk their gorgeous airport outfits, with a hilarious wig-off-and-on moment at passport control. Leigh loved exaggeration, to push the actual to a jaw-dropping fragment of a new perspective or possibility. Later, when we got on the plane, a stewardess hand-delivered me a note from chair F43. Looking over, I saw a quiet, bespectacled businessman. More flattering notes from F43 followed. At the baggage hall, I started to walk over to F43, but luckily before reached him I saw, out of the corner of my eye, Leigh and Michael watching, doubled over with laughter. Detour.

Another time, Leigh and I left dinner at the villa of the British ambassador to the former Yugoslavia to settle in the garden. We rejoined the party later and Leigh fabricated that I had, during this time, gotten very ill, lain down in the master bedroom and then thrown up on the duvet. (Leigh had meanwhile quickly hidden the duvet in the back of the garden). Everyone believed his story instantleigh. Live as variously as possible.

While on tour, Leigh often wore short trousers with a matching jacket, knee socks with medium-heeled lace-ups, a badly cut, ash-coloured wig and no makeup. Once, Leigh, David Holah, Dawn Hartley and I took a bus ride to Lake Bled in Slovenia. We arrived magically high up in the mountains, with our heads in the clouds. After some time taking in the scenery, Leigh murmured, ‘Nature is truly shocking’.

Ellen van Schuylenburch is a dancer, dance teacher and founding member of the Michael Clark Company.

Dave Swindells

Leigh Bowery at Limelight, London, 1987

© Dave Swindells c/o Unravel Productions

Dave Swindells

In 1990, Leigh Bowery and promoter Tony Gordon co-presented their first club night since the closure of Taboo in the summer of 1986. It was bound to be special in one way or another. For 18 months, Taboo had been a weekly gathering place and a kind of epicentre for a loosely knit network of designers, artists, musicians, stylists, filmmakers and hangers-on.

There was little likelihood of recreating the same kind of cultural impact at their new club night, Cambodia – the explosive stories about huge raves happening all over the home counties had shifted the focus away from the artfully dressed demi-monde in West End discos (with the notable exception of the spectacular Kinky Gerlinky parties, where Leigh was a regular performer). Still, as the nightlife editor at Time Out, I was determined to report on it. I had photographed Leigh whenever I got the opportunity from late 1984 onwards, but I hadn’t seen him since a chance meeting at the acid house night Spectrum in the summer of 1988.

Bowery’s status as a performance artist – a role he’d played at every event he had been to since about 1982 – had been confirmed when he had appeared at the Anthony d’Offay Gallery for a week in 1988. However, it was the impromptu sightings and unexpected encounters with Leigh Bowery that excited me the most. When Leigh sashayed slowly down the stairs from the balcony of the Hanover Grand nightclub, wearing an enormous, pink taffeta cape and a pink-and-yellow cloche hat, those of us below knew we were in for a show. But what kind of performance would it be? The ‘surprise’ element didn’t last long: almost as soon as he reached the dance floor, Leigh spun around in a wide dramatic sweep and the cape was thrown to the floor, revealing that he was wearing little more than pink boots, a golden bustier and a merkin to cover his manhood.

The hair clip-festooned bustier was sensational, but it was Leigh’s body – all that mountainous flesh that Lucian Freud loved to paint – that felt like the real focus, especially after years in which it had been hidden inside elaborate costumes. Leigh had performed on stage with the Michael Clark Company, but this moment didn’t appear to be choreographed at all. After throwing himself into some acrobatic shapes, his performance soon transformed into something simpler: the party host, dancing among his guests. I may have been the only photographer there, which seems remarkable in hindsight, but what was also curiously impressive is that most of the other clubbers appeared determined not to look at Leigh. It’s impossible to imagine a similar reaction today.

Dave Swindells is a photographer and the former nightlife editor at Time Out.

Dick Jewell

What's Your Reaction to the Show? 1988 (stills)

© Dick Jewell

Dick Jewell

What's Your Reaction to the Show? 1988 (stills)

© Dick Jewell

Dick Jewell

What's Your Reaction to the Show? 1988 (stills)

© Dick Jewell

Dick Jewell

By 1988, Leigh had become a close friend of mine through other mutual friendships. I’d already had the idea of recording people’s responses to art, and so when Leigh told me that Anthony d’Offay had offered him a week-long show in his gallery, it seemed the perfect opportunity to make my film. As Leigh’s first performance in a purely artistic context, there had yet to be any critique of his work. This meant that the answers to my question, ‘What is your reaction to the show?’, would be influenced only by each individual’s interpretation of the work or their relationship to the artist.

The film that followed reveals the diversity of Leigh’s audience, from the gallerist to the cleaner. Many people placed greater emphasis on what they had expected to witness, over what they had actually seen. Some thought Leigh’s daily silent performance in different flamboyant outfits behind a two-way mirror was the greatest show they’d ever seen, while others simply did not understand what they had just watched. However, for Leigh’s friends, their familiarity with him gave them a different insight into the performance. As one remarked: ‘Because Leigh’s dialogue is as powerful as his presence in a room, in this case you are getting less but seeing more.’ I’m pleased that the film places the performance firmly in the context of art in the late 1980s, from the nature of the reactions to the fashions the audience are wearing.

In the film’s conclusion, which focuses on Leigh’s own reaction to the show, he tells us how being isolated in a room for two hours each day gave him the opportunity to think about what he was experiencing, as well as other shows that he’d like to do ‘in relationship to art in general’.

I was happy to document his next ‘art’ performance at the Serpentine Gallery in 1989, as well as many others as they became more extreme in subsequent years (as did the audience’s reactions). I will never forget the combined sound of gasps, applause and airhorns blasting as Leigh ‘gave birth’ live on stage at the Empire Ballroom, a venue in which I recorded him, from among the melee, on over a dozen occasions at the club night Kinky Gerlinky. Leigh’s extrovert apparel and behaviour matched the sentiment of the club.

Another night, while dancing vigorously in a sequinned crash helmet over a full, nylon head covering, he announced to my camera: ‘Dick, hi. Anyone who is heterosexual is slim.’ After some more dancing, he continued: ‘I’m sorry, Dick, that might include you.’ He always loved to court controversy.

Dick Jewell is an artist and filmmaker based in London.

Leigh Bowery! at Tate Modern, 27 February - 31 August 2025.