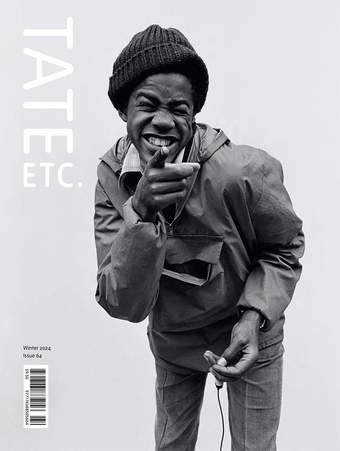

Still from Rebecca Horn’s Peformances II 1973 with Cockatoo Mask

© DACS 2024. Rebecca Horn Archive / Moontower Foundation

Rebecca Horn (1944–2024) nearly died for her art. It was 1964. She was 20, and making sculptures from fibreglass and polystyrene. ‘Nobody said it was dangerous,’ Horn professed in 2005. So she worked without a mask, steadily poisoning herself. She was soon hospitalised with severe lung damage, then confined to a sanatorium for a year.

Yet, from her sickbed, she could draw. She started sketching sculptural constructions to fit bodies like prostheses, elongating the limbs to allow the wearer to make contact with their surroundings in surreal new ways. ‘I wanted to pass on this experience of being tied to a bed, to share this experience,’ Horn later said. Shared isolation: this paradox speaks to the contradictory nature of sickness – how it restricts but also opens the body, revealing its permeability. ‘With lung fever you dream differently,’ Horn recalled: ‘dreams filled with erotically charged images. You crave to grow out of your own body and merge with the other person’s body, to seek refuge in it’.

One of Horn’s earliest body extensions is Unicorn 1970–2, which appears in Horn’s 1970 film of the same name, and in her 1973 film Performances II. In the film a woman walks from a shaded forest path into a sunlit field, strapped into a bandage-like corset that leaves her breasts exposed. On her head she wears a towering spike that extends upwards from the skull. The title of the work plays on Horn’s name (how irresistible to be a growth, a strange appendage, a weapon that is also ornament and instrument; phallic, satanic and horny), but what was once thought to be unicorn horn, known as alicorn, also alludes to poison and healing. Throughout the medieval and Renaissance periods, powdered alicorn was believed to hold magical properties. The elusive substance (true source: narwhal tusk) was used in the French court to detect poisoned food and was also thought to render contaminated water drinkable.

Still from Rebecca Horn’s Peformances II 1973 with Unicorn

© DACS 2024. Rebecca Horn Archive / Moontower Foundation

With Cockatoo Mask 1973, Horn’s concern with danger and protection is more explicit. In the associated performance, white feathers encase Horn’s face. Another person touches the bird-person’s feathers, parting them suggestively. The wings spread, and they enter. ‘The feather-enclosure isolates our heads from the surrounding environment,’ Horn said of the work, ‘and forces us to remain intimately alone, together.’ This charged performance realises Horn’s dream to ‘merge with the other person’s body,’ and the thrill at witnessing Horn’s co-performer fingering her plumage can obscure that this is a mask – the lack of which caused the invasion of Horn’s lungs. Cockatoo Mask erotically enacts the entanglement of respiration itself: breathing the same air is both promise and threat.

Who can breathe easily and who is vulnerable to the injuries of the air? In one fortnight in October, three news stories broke about microplastics. One study found microplastics in human brains for the first time; another revealed they can be passed from a mother into their unborn offspring. A third found microplastics in dolphin breath, suggesting they inhale contaminants when coming up for air. Car tyres, water bottles, cosmetics. A Hula Hoop packet dated August 1986 found in the Thames; a balloon fragment inside a mitten crab’s stomach.

Horn is a prophet of the Plasticene: the age we reside in, defined by plastic pollution entering the fossil record. Yet, in Horn’s expansive erotic imaginary, ‘making contact’ is curative as well as contaminating. American writer Audre Lorde defined the erotic in opposition to ‘plasticised sensation,’ as the power ‘which comes from sharing deeply any pursuit with another person’. In Horn’s erotics, each breath is a shared pursuit. Her body extensions encourage us to think beyond our limits, connecting the human with the animal, the forest, the field, the sky. There is no alicorn to decontaminate this shared, toxic world – only the knowledge that we are never isolated but remain ‘intimately alone, together’.

Performances II was presented by the artist in 2000 and is on display in Modern Art and St Ives at Tate St Ives. Cockatoo Mask and Unicorn were purchased with assistance from Tate Members in 2002.

Eloise Hendy is an arts and culture writer who lives in London.