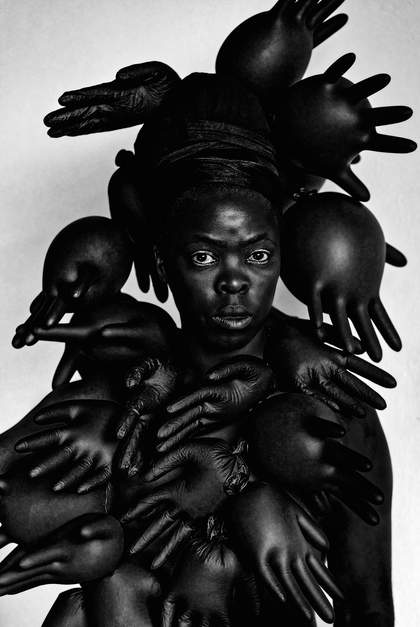

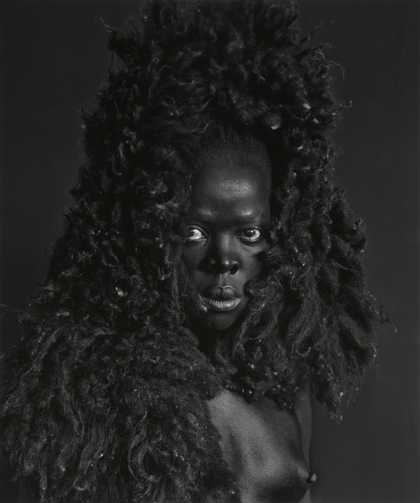

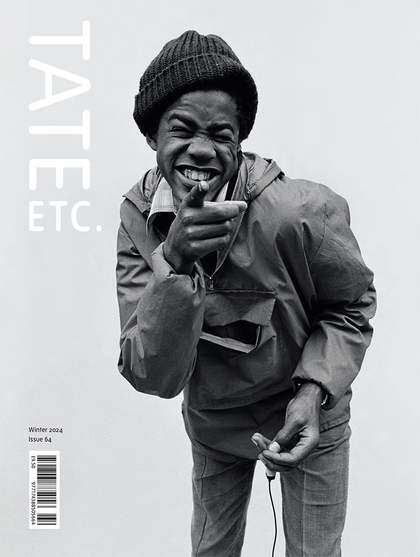

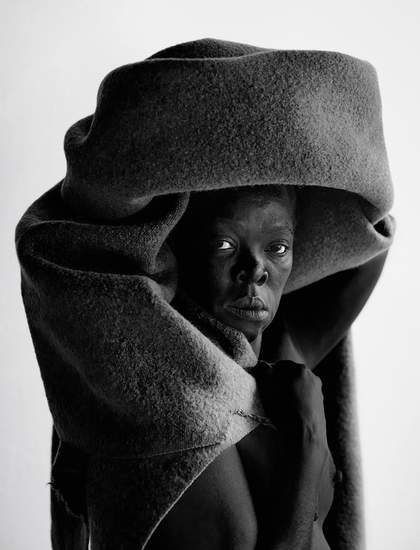

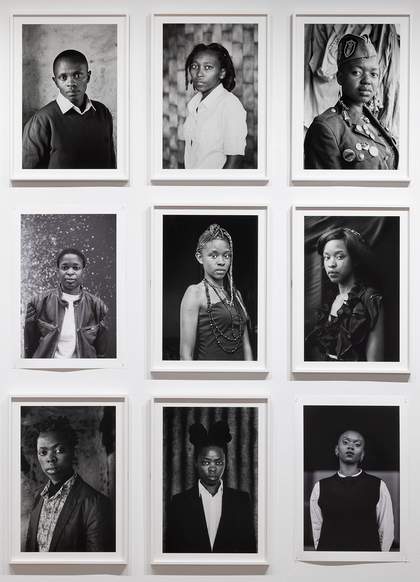

A selection of portraits from Zanele Muholi’s Faces and Phases series currently at Tate Modern, including newly added pictures taken in London of Lola Olufemi (bottom right) and artist Joy Yamusangie (middle row, second from left)

© Zanele Muholi. Courtesy Southern Guild and Yancey Richardson. Photo © Tate (Jai Monaghan)

We fall out onto the pavement. Surprised, I ask if we are headed somewhere in particular. Muholi says, ‘We’re here.’ They like to photograph their subjects on the street, in the places where they live, eat and play. Muholi begins to shoot almost immediately, capturing the pace of busy roads outside the Common Press bookshop on Bethnal Green Road. Strangers pass by and glance at the scene, cars honk, producing a wave of self-consciousness in me, but Muholi is never startled by the attention of others. Their focus is singular.

We move quickly to keep warm and complain about the weather, alternating from full body shots to intimate portraits. I try to make sense of Muholi’s technique, but the fluidity of their deft movements and the speed of the camera’s shutter leaves no space for rumination. As I experiment with different gazes, they tell me that I have come prepared, and that they are often struck by how different subjects choose to present themselves across space and time.

With gloved hands, and wrapped in a big coat and brightly coloured scarf, Muholi shoots with a precise attention to detail, seeking to preserve the specificity of their subject. I feel as if I am being shot by a true disciple of the image as I am inaugurated into the artist’s ongoing Faces and Phases series, a project that alerts us to the shifting dimensions of queer self-representation. My image willform part of a photographic history.

At many points, Muholi invokes the image as a separate entity from that which it depicts. They tell me to relax my body, to ease up on the performance of a self and to trust that the image alone will do the work. It will, as theorist Tina M. Campt reminds us, enunciate an aspiration, provide a way of looking at this Black lesbian, at this specific time, in this specific place.

I didn’t know then that my image would be inserted guerilla-style into Muholi’s current exhibition at Tate Modern. They do not care for institutional graces: unframed, they pin the new images taken in London onto the gallery walls, alongside portraits of Black lesbians from across the globe. This gesture indicates their belief that propriety cannot and will not sever the connections between Black queer people.

‘What do you want to say?’ Muholi says earnestly and often, looking straight at me, keeping the camera low and their centre of gravity lower.

After the shoot, we walk to the apartment they are staying in on Columbia Road. They offer me popcorn, set up the camera, and interview me about what it means to be Black and queer in London. I point to the material conditions, the economic, political and social structures and relations, that make ‘Blackness’ and ‘queerness’ both possible and impossible.

Choosing my image for the series is a collaborative process. We go back and forth until we settle on one we find striking. As we flit through the images of my peers, the other Black working-class artists, cultural producers, writers and community organisers from London included in the series, I notice that in their portraiture, Muholi unearths new parts of the city, be it in South Africa, Botswana, Britain or the United States.

On street corners, among the violence of social life, against metal slats, at the back end of a back road, Muholi foregrounds their subjects, leaving room for their steely or soft, hesitant or wandering gazes to define the frame.

Zanele Muholi, until 26 January 2025.

Dr Lola Olufemi is a Black feminist writer and Stuart Hall Foundation researcher based in the Centre for Research and Education in Art and Media at the University of Westminster. Her work focuses on the political uses of the imagination – its relationship to political demand, cultural production and futurity.

Supported by the Huo Family Foundation with additional support from the Zanele Muholi Exhibition Supporters Circle and Tate Americas Foundation. Research supported by Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational in partnership with Hyundai Motor. Organised by Tate Modern in collaboration with the Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris, Gropius Bau, Berlin, Bildmuseet at Umeå University, Institut Valencià d’Art Modern, Valencia, GL Strand, Copenhagen, National Gallery of Iceland, Reykjavik, and Kunstmuseum Luzern, Luzern. The media partner is Dazed. Curated by Carine Harmand, John Ellerman Foundation Curator, Tate Liverpool, Yasufumi Nakamori, former Senior Curator, Photography, Tate Modern, Amrita Dhallu, Assistant Curator, International Art, Tate Modern, Sarah Allen, former Assistant Curator, International Art, Tate Modern, and Keryn Greenberg, former Head of International Collection Exhibitions, Tate. The exhibition in 2020 was supported by the Zanele Muholi Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate International Council, Tate Patrons and Tate Members.