This year, the UK’s most prestigious art prize celebrates its 40th birthday. Since its inception in 1984, the Turner Prize has acted as a barometer of British contemporary art, shining a light on some of its most exciting proponents. Tate Etc. sits down with this year’s four nominees, whose rich and varied work speaks in different ways to Britain’s past, present and future.

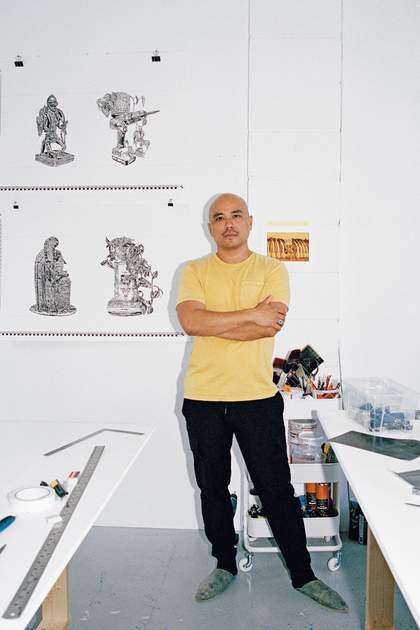

Pio Abad

Abad’s work considers cultural loss and colonial legacies. His nominated exhibition, To Those Sitting in Darkness at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, includes drawings and sculptures which depict and juxtapose artefacts from Oxford museums, and highlight their overlooked histories

TATE ETC. What materials do you like to use, and why?

PIO ABAD My work takes on a wide range of forms, from textiles and installations to bronzes and even augmented reality, but everything emanates from drawing. My most important tools are my Rotring Isograph pens, which are used in architectural design.

My drawings depict artefacts from narratives that have been purposefully erased or conveniently forgotten. The process of translating these objects into ink drawings is akin to cartography: mapping their coordinates and over-describing their details through the fine lines of the pen, committing them to memory and asserting their presence as relics and witnesses.

ETC. Does the idea for a show or a body of work come all at once or does it arrive over time?

PA It takes me a long time to produce a body of work, as it is often a combination of extensive research, labour-intensive processes and collaboration. For instance, The Collection of Jane Ryan & William Saunders took ten years to complete, and I’m still not sure whether it’s finished. Time is a sculptor in my work.

ETC. How important is scale?

PA Though my work attempts to cover a wide sweep of historical events – from the Marcos dictatorship in the Philippines to the Bolshevik Revolution, the ransacking of the Kingdom of Benin to the death of Margaret Thatcher – the forms that the works take are objects relating to the body: a postcard, a bracelet, a houseplant and a handbag.

The histories I depict can only make sense if the viewer can relate these stories to their own bodies. That sense of proportion is essential. I think history has to be made ergonomic for us to be able to grasp it and learn from it.

ETC. How does history, including family stories and heritage, make its way into your work?

PA History is the armature of my practice.

I grew up in a very political household in Manila. My mother and father met as trade union organisers in the 1970s, who then had the unenviable task of helping rebuild democracy after the fall of the Marcos dictatorship in 1986. My commitment to art as a tool for pedagogy and for imagining possibilities where politics becomes insufficient has been shaped by my parents’ devotion to societal change.

An essential aspect of my work is my collaboration with my wife, jeweller Frances Wadsworth Jones. We are drawn to the recurring role of jewellery as the most intimate and ultimate witness to political and cultural upheavals. The collapse of autocracies and the impunity of empires are often crystallised into a particular diamond or piece of jewellery.

ETC. What is inspiring you right now, outside of art?

PA Frances and I are expecting our first child in a few weeks. There is nothing more inspiring than that.

Claudette Johnson

Nominated for her solo exhibitions Presence at The Courtauld Gallery, London, and Drawn Out at Ortuzar Projects, New York, Johnson is noted for her intimate portraits of Black women and men, which counter their marginalisation in Western art history

TATE ETC. What materials do you like to use, and why?

CLAUDETTE JOHNSON I enjoy working with pastels because they allow me to lay the foundations for a drawing or painting very quickly. The colours are pure and strong, and they can be used to create strong linear drawing, or produce very subtle, fleeting effects when dragged across a rough surface. Pastels also have a tactile quality that allows me to work in an almost sculptural way. It can feel as if I am moulding the forms as opposed to simply applying a material to a flat surface.

ETC. Where do you go to make, or think about, your work?

CJ I have a lovely studio that is like a home from home. For me, good natural light, flat walls, and a large floor area where I can move my easels around easily are essential. Although it’s in a built-up area near a busy road, most of the sounds I hear come from the seagulls’ screeching as they careen over the derelict warehouse nearby.

ETC. How does your environment influence the art you produce?

CJ I’ve always lived in the city, so I have no experience of working in an area that is predominantly green. I’ve always wanted to go somewhere like St Ives to see whether the light influences my colour choices. It occurs to me that the oblique, flattened planes in my works could be a response to the urban environment. In all my work the figure is slightly at odds with its setting, just as I feel cities are fundamentally unsympathetic to human bodies.

ETC. Does the idea for a show or a body of work come all at once or does it arrive over time?

CJ I try not to produce work with a specific show in mind as this makes me anxious and can influence my decision making. I like to make work that continues in the stream of ideas that have always motivated me. For example, I’m currently working on a painting on Ugandan barkcloth (a fabric often used in funeral ceremonies), which I initially had the idea for in 2020 after the murder of George Floyd. I felt such despair at the way that Black men are viewed as dangerous just by dint of breathing.

ETC. How important is scale?

CJ When I first joined the undergraduate Fine Art course at Wolverhampton School of Art in 1981, I had been working no larger than A1. Then, one day, a tutor suggested I scale up. Discovering that I could work larger than life was a revelation. Suddenly, I could get behind a line with my whole body. I find that, at this scale, the figures can hold the viewer in a difficult-to-walk-away-from dialogue.

Jasleen Kaur

Creating sculptures from everyday objects, Kaur’s work explores cultural inheritance, autobiography and refusals. Her nominated exhibition Alter Altar at Tramway, Glasgow, conveyed the artist’s upbringing in the city, animated by an immersive sound composition

TATE ETC. What materials do you like to use, and why?

JASLEEN KAUR The spaces I grew up in were rich in material subterfuge: chromed plastic, wood veneers, hand-painted marble, mass-produced religious ephemera. I was interested in their social lives and the stories they narrated or kept hidden, and, over time, in how material can serve as a rebuttal or counter-narrative. It’s one reason I’m interested in voice, whether testimony or devotional song from a pre-colonial era. These are artefacts too, just less solid, much easier to erase and therefore more fugitive.

ETC. How important is scale?

JK More important than scale is when an artist moves you emotionally. When I was invited to occupy the colossal space at Tramway in Glasgow, I thought less about filling it and more about how sound might hold space – about the local neighbourhood, which was once mine, what it’s steeped in, and how to speak alongside it. In her book Listening to Images (2017), Tina M. Campt writes about ‘resist[ing] the lures and seductions of an easy reading’. Obfuscated in the images, symbols and sounds is me trying to have a conversation with my history, while dodging the role of native informant.

ETC. How does history, including family stories and heritage, make its way into your work?

JK Heritage is a complicated word because I was taught that it is definitive, or singular, and I don't understand it as this anymore. Ariella Azoulay’s theory of ‘potential history’ has been an anchor in understanding my process of thinking backwards – excavating anti-imperial histories to imagine futures. I’m totally caught up in this process of salvaging and finding evidence of other ways to live. When you dig, you inevitably dig around family histories. But what I am interested in is how these intimacies rub up against wider social structures and the nation state.

ETC. In what ways does the present moment seep into your work?

JK There are several enlarged images in the show taken from news articles in 2020–1. The Kenmure Street Protests, Glasgow, Farmers Protests, Delhi and the restitution of land for the construction of a mosque in Moga, Panjab. These counter-images dispel a myth around where our solidarities lie. In the installation, they’re scattered on the floor and sit in relation to the sound work, which references my musical ancestry of plural devotional practices. So much of this is lost and covered up due to colonial violence, borders and political reform. My longing for a connection to lineage and tradition through freedom is in direct response to our terrifying world.

ETC. What is inspiring you right now, outside of art?

JK Student occupations. Solidarity networks. Organised coalitions. Marching and chanting with Parents for Palestine. Singing the songs of age-old bards.

Delaine Le Bas

Le Bas was nominated for her immersive presentation Incipit Vita Nova. Here Begins The New Life/A New Life Is Beginning at Secession, Vienna. Drawing on the rich cultural history of the Roma people and her interest in myth, she addressed themes of death and renewal through painted fabrics and theatrical costumes

TATE ETC. What materials do you like to use, and why?

DELAINE LE BAS Fabric – calico and, most recently, organdie – with paint. Paint works into the surfaces of these fabrics in different ways. I paint mainly outside on washing lines – when the elements change, the wind moves the paint across the fabric, and I love my lack of control over this. I embrace the drips and lines created, and allow them to become an intrinsic part of the work. A sort of handwriting emerges, related to the medium and the fabric combined. The organdie also takes and makes forms of its own, due to its structure as a material. This is interesting for shape when making costumes, and I am making more sculptural forms with it, which I then stuff with lavender and hay. I think of what we no longer have now, all the beautiful things that were historically created out of materials that don’t survive over long periods of time. Creating installations, structures and paintings from these fabrics, which bodies can move within, through and over, creates a different experience to that of fabric on a wall or placed behind glass.

ETC. Where do you go to make, or think about, your work?

DLB Anywhere and everywhere. Books/journals/ diaries – I always carry at least one book to write and draw in. A word in a conversation can be a starting point. Often I look back and see that just by creating a small drawing, I had already manifested the basis of a work years before, and sometimes without having revisited it at all in the interim.

ETC. How does the environment influence the art you produce?

DLB Creating installations within different environments interests me. Creating new structures within existing ones, and seeing how these structures and installations then reconfigure and morph into other spaces. I like to ‘soak up’ the environment and move with the work within the space. There are many excit- ing possibilities in terms of scale, how materials work differently within a very particular environment, and the ways you can play with this.

ETC. How might your work change people’s perceptions?

DLB My work is a personal journey in the world. My identity might cause my work to be viewed with certain perceptions and expectations. I am not here to create works that reflect a specific identity, only that of my own and how it feels to be in this world now.

ETC. What is inspiring you right now, outside of art?

DLB My grandchildren.

Turner Prize 2024, Tate Britain, 25 September 2024 – 16 February 2025.

Supported by The John Browne Charitable Trust and The Uggla Family Foundation. The members of the Turner Prize 2024 jury are Rosie Cooper, Director of Wysing Arts Centre; Ekow Eshun, writer, broadcaster and curator; Sam Thorne, Director General and CEO at Japan House London; and Lydia Yee, curator and art historian.

The jury is chaired by Alex Farquharson, Director, Tate Britain. Curated by Linsey Young, Curator, Contemporary British Art and Amy Emmerson Martin, Assistant Curator, Contemporary British Art, with Sade Sarumi, Curatorial Assistant, Contemporary British Art.