Joseph Mallord William Turner

A Hurricane in the Desert (The Simoom), for Rogers’s ‘Poems’ (c.1830–2)

Tate

This heat is biblical ’n’ so is this image. My eyelids drip an’ my vision blurs from the oil of my own swelter. A Hurricane in the Desert, Turner’s title, only a peel of paper from his series of vignettes, his little vines of surreal ’n’ mundane moments of beauty ’n’ dread, mostly made for poets to accompany their written work in books... Dreams are like vignettes, aren’t they? Little night-time explosions of our recycled recollections from the forests in our heads that then sandstorm our brains.

Do you remember pre-internet dreams? I think my generation were the last to have them, cut short by the arrival of the family desktop. Mine were a lot like this, divine scenes of beauty ’n’ doom, of all the stories told in class, of the religious claymations we watched as children, of the images in print-outs and books of scripture that still haunt my mind. It’s as if all of it were swept up specifically to enter my night-time world of which I am a VIP. That was the first time I felt pre-pubescent bugs in my stomach, feelings of festering shame. It all lies in this image somehow, like how artists of Turner’s darkened times hid in their work their deepest secrets. I had quite a strange dream as a child where I was kissing a boy cross-legged in an indoor play centre. We were two animals hacking at each other’s mouths as I slammed my hands violently onto the buzzer-like buttons on the wall that produced animal sounds – moos and oinks, the neighing of horses. It’s all choking me back to the guilt of sitting in class, staring at these worlds with the shame of my excursions echoing from the very night before.

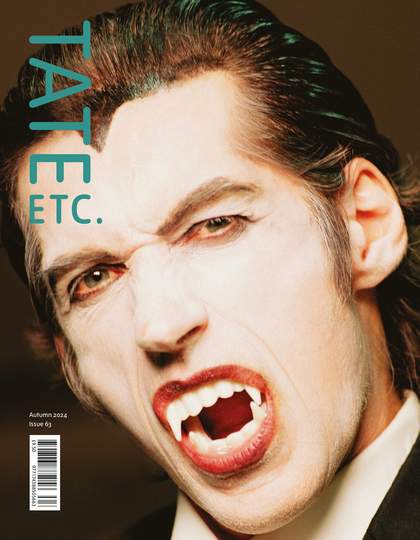

My night-time worlds used to only consist of images like Turner’s simoom of molten bodies, animals truncated to ground ’n’ dirt, in a moment that whispers we are all of the same blood an’ water. In all its horror, it somehow also looks like peace, a blissfulness, the way the ground meets the sky seamlessly, the way the sun bleeds into the air with each stroke of cyclone. I’d pay to be standing in that cavern of gravel ’n’ screams, even after moaning about the heat I am standing in right now, looking at the picture’s stillness. It feels of the end, this numinous vignette. It feels as if this is the last hour on earth. It’s how Lucy describes Dracula lurking in her bedroom: ‘a whole myriad of little specks seemed to come blowing in through the broken window ... wheeling and circling round like the pillar of dust that travellers describe when there is a simoom in the desert’. I wonder if I’ll wake up with Turner at the end of my own bed tonight, paintbrush in hand.

I see the simoom one last time, the very word meaning ‘poison wind’, ’n’ it’s as if, starved from the latter, I’d take the poison right now. I can hear the animal screams and the last rattles of human breath. It reminds me of this dream I had that I’ll leave here for Turner, as I know he liked poems:

There was once a horse standing in a dust storm,

it had a nuclear bomb mushroom cloud spray painted in hot pink on its side it eye’d me to follow ’n’ without words we spoke,

’N’ the sounds of Saturn matched the movements of the sand spirals, there aren’t enough for castles no one can make them anymore

’N’ so I felt a warmth I had forgotten could exist,

with each stroke it glistened like the dancing of the seas from a before

A Hurricane in the Desert (The Simoom), for Rogers’s ‘Poems’ was accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest in 1856 and is on display at Tate Britain alongside a selection of the artist’s small watercolours.

Luna Carmoon is a London-born screenwriter and director. Her debut feature film Hoard premiered at the Venice International Film Festival last year.