Paul Pfeiffer

Morning After the Deluge 2003 (still)

© Paul Pfeiffer

KATY WAN I’ve been thinking about your work for some years now, beginning with The Saints 2007, a video work which takes as its starting point the 1966 World Cup Final between England and Germany, which, along with Morning After the Deluge, was recently donated to Tate as part of the D.Daskalopoulos Collection Gift. So, I came to your work thinking it was mainly about sport and spirituality. But as I delved deeper it took on a more expanded view, say, of figures in the public sphere.

But Morning After the Deluge 2003, which is going on display at Tate Britain this summer, is quite different. In this work, you turn to landscape and art history via a video installation that takes its name from Turner’s famous painting, and focuses on the sun as a protagonist. In the artwork, footage of Cape Cod sunsets are edited together so that, rather than the sun appearing to rise or fall, it is actually the horizon line that moves. Given that there are no people present in the work, do you consider it an anomaly in your wider practice?

PAUL PFEIFFER For me, the through line between these different works is that they share an intention to provide a simple and intuitive entry point for viewers into the relatively abstract or counterintuitive concepts the work seeks to explore. My parents were both church musicians and were also involved in the study and performance of folk music from the Philippines. I think I inherited from them an affinity for populist modes of address attuned to the emotionality and non-specialist sensibility of a broad public audience, as in a religious congregation, a town hall assembly, or a stadium crowd. So, while I believe in the analytical tools of critical engagement, and I’m drawn to the esoteric aspects of language and perception, I’ve always tended towards the idea of filtering these things, or clothing them, in a common language.

In Morning After the Deluge, I thought, there is nothing more mundane and yet profound than the impulse to stop and watch or film a sunrise or a sunset. It’s one of the most ubiquitous tropes in photography. It’s an immediately relatable, everyday scenario and, at the same time, it’s an otherworldly spectacle and, therefore, has the potential to embody the uncanny.

KW This year marks 20 years since Tate Etc. magazine published a short piece on this same work (Issue 2, Autumn 2004). I loved the passage where you discuss technology mediating perception. You talk about this experience of being a child in the Philippines and consuming American popular culture through television. Even though your practice has evolved, it comes back to something very early in your life.

PP Absolutely. The creative process is a way of making sense of the arbitrary details of place and time you were born into, and a discovery of how you’re braided into public histories and shared memories. To me, that formative revelation deepens over the course of your life when you realise that details of your individual existence serve as an embodiment for things that are held collectively.

JMW Turner

Light and Colour (Goethe’s Theory) – the Morning after the Deluge – Moses Writing the Book of Genesis c.1843

© Tate

KW There is heightened public discussion now, maybe more so than when the work was made in 2003, about the human impact on nature and the planet. In some ways, Morning After the Deluge challenges the human-centric view that we are the horizon line – in your work, it’s the horizon line that moves up and down. Do you welcome that environmental reading of the work?

PP I totally welcome it. I’m interested in the dimension of Turner’s work that points to the fact that, arbitrarily, he’s born into an era that is defined by empire-building. His landscapes speak to it. So, it’s intriguing to me that he’s dealing with timeless phe- nomena, such as light and space, the ocean and sky, and yet he’s considered in retrospect as somebody who chronicled industrialisation and the earliest days of global colonial enterprise.

I associate his paintings, and Turner himself, with Heart of Darkness (1899) by Joseph Conrad. That was written later, but they have a similar resonance in that they both invite a double reading of the timelessness and universality of perception and, at the same time, the emergence of a specific history.

KW Am I correct in thinking that you first came across the Turner painting in Jonathan Crary’s book Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century (1990)? I love the arbitrariness of that discovery.

PP Totally. I was attracted to the title and the central idea that, as modes of production change, so do modes of perception. When I got into it, I discovered that Crary frames this idea through a history of popular culture, and that the evolution of perception could be tied to the optical devices that were circulating on the street for entertainment. In some ways, it confirmed the intuition that I had regarding the depth of seemingly superficial things or popular culture.

I recall Crary formulating a top-down perspective in which the eye of God had been the determining perspective in society. So, rules came from above. But, he says, there was a moment in history when, via popular devices such as the zoetrope, people became aware of the way in which the body could be a centre point of perception. So, the top-down perspective embodied by God was turned 90 degrees and relocated in the viewer.

KW That’s the fundamental tension, isn’t it? In Turner’s painting, he’s taking this quintessentially biblical subject and qualifying the power of God, while at the same time undermining it, because new technologies emerging, specifically the camera obscura, are enabling artists and scientists to develop greater empirical scientific knowledge.

PP It’s enigmatic to me because, in a way, you could read that as a rationalisation of power, away from a belief in the sacred and towards a secular vision of democratic society, or at least law-bound society. For a long time, this evolution was treated as a simple teleological form of progress, from the pre-modern to the modern. But in the current moment, I feel that there is a growing space to consider a more blurred relationship between technological innovation and the spiritual dimension. There are lines of continuity that connect a current, almost magical, thinking around technology to a pre-modern version of a belief in sacred sources, or the intervention of gods in worldly affairs.

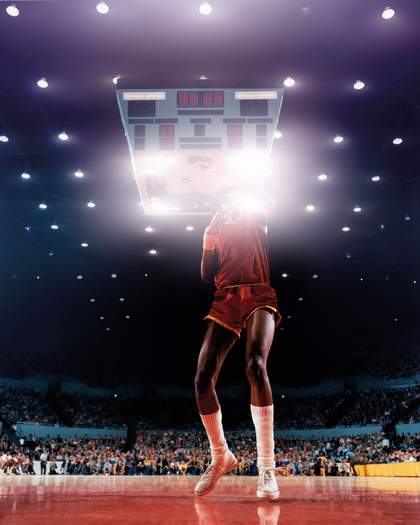

Paul Pfeiffer

Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse #6 2001

© Paul Pfeiffer

Paul Pfeiffer

Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse #17 2004

© Paul Pfeiffer

KW I can’t help but think about Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, your ongoing series of edited images of NBA players, begun in the early 2000s. You’d think we’d have cast aside the idea of apocalypse, but people still believe strongly in this notion. Do you have thoughts on why?

PP Again, perception is something that evolves. What is considered absolutely true one day is revised on another. At any given time, what is naturalised as reality is haunted by the ghost of something else, something beyond what we naturalise as real. We’re seeing this again with climate change. There is a sense that everything we consider to be a given could change rapidly, and then where will we be? In a way, this brings me back to the notion of the uncanny as a fundamental aspect of human experience. There are certain moments when, in a pronounced way, one becomes aware of one’s sensorium as an envelope beyond which is something that we can’t perceive. And now it’s succeeded by AI...

KW In those gaps, there is room for people to question what is real and what isn’t. I guess this is where conspiracy theories arise. While it’s important to question the news media or propaganda, we’re now in this wild west of no regulation around the information put into the public sphere. You often have to go by reputation of news sources. But who is the arbiter of that?

PP In a way, I associate what you’re saying with the notion of a horizon line. The horizon line is a place that appears like an anchor point to stabilise perception. So what’s happening in Morning After the Deluge is that the horizon line is made unstable and, by association, there is no longer any ground to stand on.

Paul Pfeiffer’s Morning After the Deluge is on display at Tate Britain alongside JMW Turner’s Light and Colour (Goethe’s Theory) – the Morning after the Deluge – Moses Writing the Book of Genesis. It is one of over 110 works donated to Tate through the D.Daskalopoulos Collection Gift, many of which will be going on display at Tate Britain and Tate Modern over the coming months.

Paul Pfeiffer is an artist who lives in New York. He talked to Katy Wan, Managing Curator, D.Daskalopoulos Collection Gift.