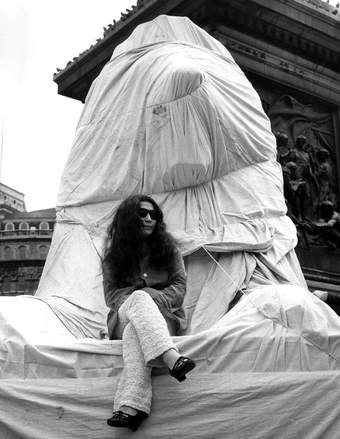

Yoko Ono in London, 1966

© Roger-Viollet / TopFoto

Viv Albertine

When I was about 16, one of my little gang of girlfriends brought Yoko Ono’s book Grapefruit (1964) into school and we passed it around between us like a little yellow jewel. You were allowed to keep it for a couple of days before you had to bring the book back so the next person could look at it. We carried it around like a totem. We didn’t show it to other people; it was something between us, something secret.

I was studying at a big comprehensive school in North London, yet Yoko’s quiet, poetic instructions spoke to me and opened my mind. I got her – how she looked, her words, her actions. She was the first woman artist I ever took notice of, and she woke me up to the idea that there was another way to think and another world out there.

If Yoko’s work can find its way to young people, they will respond to it. I loved the album cover she made with John Lennon for Two Virgins (1968); it did more for me in terms of feeling comfortable in my body as a teenager than any magazine article, or anything written by a doctor or a journalist. It said it all, without any words: two ordinary people in their ordinary bodies – this is normal.

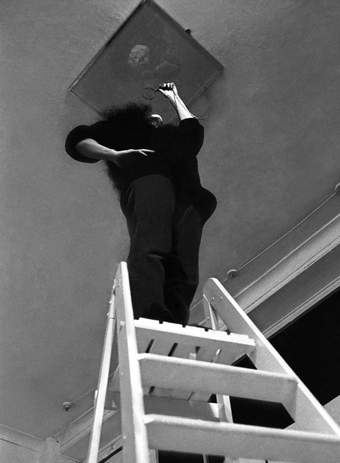

John Lennon’s account of the night he met Yoko and encountered her Ceiling Painting in 1966 has stayed with me since I read about it in my teens. How he climbed up a tall ladder and how the climb led to the word ‘YES’ on the ceiling. He was relieved that the resolution was positive rather than negative or dismissive. To me, that piece encapsulates the sensitivity of Yoko’s work. It’s direct, revealing, finely tuned, but not excluding.

In 1971, I went to Hornsey School of Art. We had a lesson with a visiting tutor where we did drawings in the open air all day; then, without looking at the drawings, the tutor told us to tear them up and throw them in a stream. Yoko did that years earlier in 1964’s Painting to Exist Only When It’s Copied or Photographed – yet, shockingly, we were never taught about Yoko Ono at art school. She’s influenced so much art and music but so often goes uncredited. The Painting to Exist piece is anti-careerist, unprecious; it’s so punk. I’ve taken her attitude with me my whole life. It’s at the very root of me.

A few years ago, I saw Yoko play at Cafe OTO in London with Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth, where she performed a moving piece about Kyoko, her daughter. Being a mother myself, I found it incredibly brave and honest. In 50 years, I’ve never failed to be affected by what Yoko does.

Viv Albertine is a musician and writer. She is currently writing a book for Fern Press based on her archive spanning over 50 years.

Cindy Sherman

Yoko Ono is one of my idols. A hero and a maverick, she has always been a great inspiration. Fearless and ferocious, and yet gentle and kind. The singular way she approaches art making should be a lesson to all young creatives aspiring to make it in their field. She takes simplicity and makes it profound; complexity is rendered to its pure essence. She is a seer: she sees through the chaos of our planet and, without negativity, she brings hope and optimism.

Cindy Sherman is an artist who lives and works in New York.

Yoko Ono

Ceiling Painting 1966 in Unfinished Paintings & Objects by Yoko Ono, Indica Gallery, London, 9-22 November 1966

© Yoko Ono. Photo: Graham Keen / TopFoto

Yoko Ono

Ceiling Painting 1966 in Unfinished Paintings & Objects by Yoko Ono, Indica Gallery, London, 9-22 November 1966

© Yoko Ono. Photo: Graham Keen / TopFoto

Beverly and Elizabeth Glenn-Copeland

For many decades, Yoko Ono has been a multi-disciplinary trailblazer in the worlds of music, and visual and performance art. She has encouraged generations of young artists to come together to actively create – not the staid works demanded by the marketplace but art created in the spirit of true innovation.

An artist extraordinaire from the moment she hit the scene in the 1960s, she embodies feminism and activism in radical ways by first identifying, then pushing, boundaries few of us knew were even there. We are blessed to have her among us.

Beverly Glenn-Copeland is a singer-songwriter and activist living in New Brunswick, Canada. His wife, Elizabeth, is a writer and theatre artist whose work is rooted in a commitment to environmental and social justice.

Elvis Costello

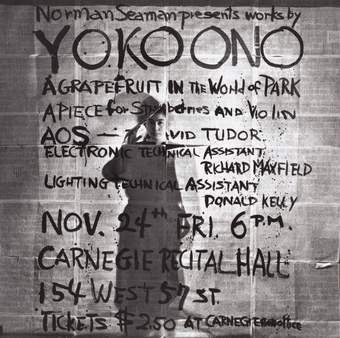

At a recent photography exhibition at the Morgan Library in Manhattan, I saw an image of a figure in shadow, obscured by newsprint covered with inked lettering: the playbill for an art event at Carnegie Hall, dated 1961. The figure was Yoko Ono, long before she had entered the viewfinder of popular culture.

Our first meeting was at a New York music studio in 1983. Yoko was making the album Every Man Has a Woman Who Loves Him (1984) and had invited me to record a track – a cover of her 1981 song ‘Walking on Thin Ice’ – while simultaneously mixing the raw and unpolished tapes that would become Milk and Honey (1984), the final John Lennon and Yoko Ono album, released three years after his death.

Over the speakers in the studio, a familiar voice could be heard joking with the band between takes. With the studio lights dimmed, it was as if John was out there, just past the glass. It must have taken a lot of strength for Yoko to hear that every day during recording.

‘Walking on Thin Ice’ had been the first music Yoko released after her husband’s murder. To cut the song again was daunting. I needed to go somewhere I had never been, work with someone I didn’t know.

The great New Orleans producer and songwriter Allen Toussaint answered the call, guiding us to a unique version of the song. It was my first but not my last work with him: our collaborative album The River in Reverse (2006) would be completed back in New Orleans while the city was still under a night-time curfew following Hurricane Katrina.

The unseen role of the artist is as creative catalyst, marrying different elements together. I will be forever grateful for Yoko’s invitation 40 years ago.

Elvis Costello is a songwriter who lives in New York.

Photograph by George Maciunas conceived as a poster for Works by Yoko Ono, Carnegie Recital Hall, New York, 24 November 1961

© George Maciunas. Digital image: The Museum of Modern Art,

Ashish Gupta

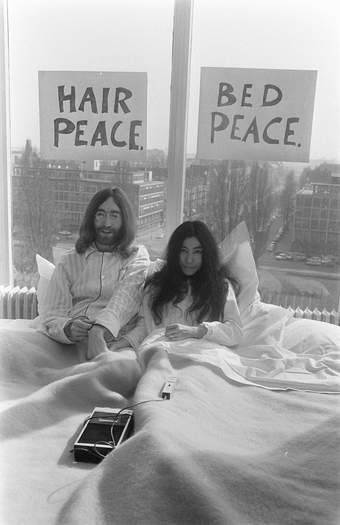

I discovered Yoko Ono's art some years ago while researching protests and protest slogans for my Autumn/Winter 2017 collection. Text has always been such an important part of my work as a fashion designer. A black and white photo from one of Yoko and John Lennon’s Bed-Ins for Peace really resonated with me and it was duly printed out. That photo stayed on my studio wall for many years.

More recently, for the staging of my Spring/Summer 2024 show – my first runway show since COVID – I thought of Yoko’s Bed-In image again. The artist Linder and I designed the show as a dream spectacle played out around a swan-shaped bed in which a man lies sleeping, dreaming of peace and love and sex and beauty. The bed becomes a site of slumbering protest against an increasingly hostile world.

Yoko’s work demonstrates that effective non-violent protest must be a kind of performance – a type of theatre – and that the audience for this theatre is as important as its participants. This ability to integrate her messages into her work with humour, simplicity and provocation is what makes her ‘theatre’ so accessible.

Messages like Hair Peace and Bed Peace and WAR IS OVER! If You Want It are, sadly, as staggeringly relevant today as they were in 1969.

Ashish Gupta is a fashion designer based in London and founder of the clothing label Ashish.

Olafur Eliasson

When I received the LennonOno Grant for Peace in 2016, I was impressed that the prize ceremony was itself a highly moving work of performance art. Together, approximately 200 guests all took a boat to the island of Viðey, across the water from Reykjavik, and walked some 400 metres to view Yoko Ono’s IMAGINE PEACE TOWER, a memorial to her husband, symbolising their work towards world peace. It was incredibly stormy and many of us were dressed for a celebration, not for the weather.

At the site, a choir began to sing John Lennon’s ‘Imagine’ (1971) and the mood shifted quickly, reflective of both the message of the song and the sight of the brilliant column of light emanating from the stone monument, created by powerful projectors aimed towards the sky. It was very poignant, the act of singing ‘Imagine’ together around this light, visible even from afar, in the worst weather imaginable.

Yoko Ono read a speech as the wind tried to tear the papers from her hands. Everyone stood in dead silence as we focused on her words. It was truly inspiring to see her sense of purpose and conceptual rigour, and to witness her focus on realising her vision, in the face of the wind and the rain.

Olafur Eliasson is an artist based in Copenhagen and Berlin. In 2019 he was appointed Goodwill Ambassador for renewable energy and climate action by the United Nations Development Programme.

John Lennon and Yoko Ono perform their Bed-In for Peace at the Hilton Hotel, Amsterdam, March 1969

© Penta Springs Limited / Alamy Stock Photo

Kate Hudson

The red thread running through Yoko Ono's work is her intense commitment to peace. From the Amsterdam Bed-In during the Vietnam War to the monochrome messaging in block capitals on public billboards, it’s been an ever-present theme in her art and performance over the decades.

But her commitment goes beyond the visual and cultural to include the political too. It was my privilege to be part of the peace delegation to the United Nations in New York in 2005, where Yoko Ono spoke against nuclear weapons on our behalf. As a child in wartime Japan, the atom bombs helped shape her consciousness and life’s work. Her message to the UN was remarkable, and her concluding words have stayed with me ever since:

‘A dream you dream alone is only a dream. A dream you dream together is reality. IMAGINE PEACE. I love you.’

Kate Hudson is General Secretary of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.

Mary Anne Hobbs

My favourite encounter with Yoko Ono's art was her Wish Tree at Manchester Art Gallery in 2013, for Manchester International Festival. The installation was first created in 1996 and it’s since been reimagined in different locations around the world.

The branches of the living tree were adorned with small tags, upon which visitors had written their wishes at Yoko’s invitation. Reading the wishes of so many strangers, in such a simple and distilled form, was a beautiful experience. Each wish was selfless and warm, gifted to a person in need, or the natural world, or a good idea.

There were hundreds of tags on the tree. Nobody had written:

‘I want to be rich’

‘I want to be famous’

For me, the small ritual act of externalising and writing down a wish, and gently tying it to the branch of a tree, transforms the wish into an intention.

Trees communicate through complex underground networks. When the Wish Trees are replanted, I wonder if they carry echoes of the human messages that once adorned them back into the dirt, the soil, our shared ground.

Welcome to Tate, Yoko. We love you.

Mary Anne Hobbs is a DJ and music journalist who hosts the BBC Radio 6 Music weekday mid-morning show.

Wish Tree 1996 at Poetry Foundation, Chicago, 10 May - 22 August 2019

© Yoko Ono. Photo: Jason Branscum

Thurston Moore

In the late 1990s, I was performing at a Fluxus event in New York City, held in tribute to the artist-provocateur Al Hansen. The celebration featured a dynamic array of performers, including Beck, Marianne Faithfull, Dick Higgins and Cat Power. The trio of musicians I was performing with decided to play an improvised piece of unleashed, amp-blasting guitar and synth noise, while a male go-go dancer writhed his barefoot, shirtless, oiled-up body on stage for all of five minutes.

The celebrity audience was hip yet polarised – if not entirely horrified – by the sonic assault and groaned in collective relief when we finally unplugged. Yoko Ono had been sat at a table front and centre, and was visibly the only person genuinely smiling. She then stood and applauded, ‘Bravo! Bravo!’

Soon after, I was asked to join her and the sound artist DJ Spooky to perform her piece ‘Mulberry’, which was first recorded in 1968. Yoko explained that the impetus for the original composition was her memory of childhood during World War Two, crouching beneath the mulberry bushes in her home country as American jet fighters roared overhead, terrorising the blue skies. The concert was held outdoors in Lower Manhattan and Yoko wailed, howled, intoned and wept, deep ululations pouring from her heart and soul as DJ Spooky and I conjured a sonorous soundtrack informed by her emotional recollections. This was Yoko’s music, this was her art, her soundworld, her communiqué through the medium of performance and being in the now, praying for all the people to hear loud and clear: a cry for resistance to violence, to hate, to oppression, to guns, to war.

Yoko would subsequently invite me to tour with her across Europe to present ‘Mulberry’ alongside other works, mostly playing small museum spaces in areas of the world that rarely had the chance to experience her radical expression. Much like at that Fluxus event, where we had first met years prior, the music would be met with mixed reactions. But this was Yoko’s spiritual genius at work and play – challenging preconceptions of the world as she had known it to be, and always having faith in the possibility of recovery and salvation through the collective power of art, where the personal and the political come together to serve one astounding truth: giving peace a chance.

Thurston Moore is a musician living in London, best known as the founding member of the New York alternative rock band Sonic Youth. His memoir, Sonic Life, was recently published by Faber.

Ei Arakawa-Nash

I had mixed feelings when, immediately after September 11 2001, Yoko Ono published the WAR IS OVER! If You Want It ad in The New York Times – a revival of the peace campaign that she and John Lennon had launched in 1969. In the wake of the attacks, I felt a degree of shame about the privilege of my own Japanese pacifism, and I found it easy to project some of that on to her.

Although I was finally getting the hang of life in New York City, having moved there from Japan three years earlier, I remember the alienation I felt when visiting her retrospective exhibition YES Yoko Ono at the Japan Society earlier that year. At that point, I was an aspiring sophomore art student at the School of Visual Arts and had just decided to transfer from the Design department to Fine Art. Everything felt frustrating, hetero, and elitist. I couldn’t donate blood because I wasn’t straight. The very air was irritating. Back then, I am sure my English was not even fluent enough for me to read The New York Times.

Twenty years later, my view on Yoko Ono transformed. Just before COVID, I became an Asian American with US citizenship and, in 2021, we had the Stop Asian Hate movement. Around the same time, I was excited to witness Yoko Ono in Peter Jackson’s film The Beatles: Get Back (2021), made from footage taken during the recording of the album Let It Be (1970). One day, Yoko Ono is filmed doing calligraphy at the edge of the frame. She draws the Chinese character ‘Spring’, and the marking emanates sensuality. It somehow feels out of place in, and resistant to, the makeshift Savile Row basement studio where the band are recording.

Inspired, I asked musician Kim Gordon to channel this Yoko Ono for a performance at Reena Spaulings in Los Angeles, where I had recently moved. Kim amplified my ideal Yoko Ono presence and manifested an intense vocal improvisation, a gift for my post-COVID life in LA. By this time, I was with new friends from the recently formed Asian American Pacific Islander Arts Network. And, at this point, I was able to feel a Yoko Ono outside of the one I had learned from history books.

Here is the poster I made with that Yoko Ono.

Ei Arakawa-Nash is a performance artist based in Los Angeles. His Mega Please Draw Freely 2021 in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall was the first project delivered as part of UNIQLO Tate Play.

Poster made by Ei Arakawa-Nash for the performance GET BACK / GET OUT at Reena Spaulings, Los Angeles, 9 April 2022

© Courtesy Ei Arakawa-Nash

Pam Hogg

The first time I met Yoko Ono was in 2003. She’d just come off stage after singing solo at the weekly Nag Nag Nag night in a tiny basement club called Ghetto, behind what was once the Astoria music venue off London’s Tottenham Court Road. It was an insalubrious haunt of the outsider – a low-key environment for such a high-calibre artist – but she was unhindered by the modest status of her surroundings.

Yoko finished her set with ‘Walking on Thin Ice’ (1981), a track way ahead of its time. I was literally standing right in front of her, the stage so tiny – and only inches from floor level – that I could easily have reached out and touched her. When it came to the high-pitched staccato wails she was a little short, and, without thinking, I chipped in, catching those really high notes and singing them with her.

The backstage area was hardly bigger than a cupboard and normally crammed with people, but, in utter respect for Yoko, an orderly queue formed. When it was my turn, she took my hand; it was like meeting a modest queen.

The second time we met was in 2013, when she curated Meltdown festival at the Southbank Centre. I’d dressed musicians Siouxsie Sioux and Peaches, and was backstage when a photocall was announced for all female artists. I, of course, stood back, assuming that they meant the singers, but Yoko thoughtfully ushered me back over.

Yoko was the first person who came to mind when I was collating ideas for my Autumn/Winter 2023 collection, ‘They Burn Witches Don’t They’. When the collection was shown at London Fashion Week, Yoko’s song ‘Why’ (1970) accompanied the models down the catwalk. Her music couldn’t have been more perfect, interpreted now as the cry of yet another Joan of Arc being unfairly demonised as a witch.

Pam Hogg is a Scottish fashion designer and musician living and working in London.

Peaches

I’ve known about Yoko Ono's work since I was about 14 years old. I was a huge fan of the Double Fantasy (1980) album, and I was fascinated by the 1969 Bed-Ins for Peace and the WAR IS OVER! If You Want It posters. They were forms of protest that weren’t aggressive; in that Yoko way, they gave room for people to project whatever they needed to onto them.

My first contact with her was many years later, when I was invited to play at the music festival All Tomorrow’s Parties in 2005. Yoko was headlining the third and final night. My first album had been given to her as a birthday present by Yuka Honda of the band Cibo Matto, so I was on her radar. Sometime during the weekend, we were all hanging out and she asked me to do a remix for her, which would become a new version of the song ‘Kiss Kiss Kiss’.

Then, in 2013, Yoko celebrated her 80th birthday with a special concert in Berlin, her favourite city. Because I live there, she asked me to sing her song ‘Yes, I’m a Witch’ (1974) with the Plastic Ono Band. The song totally encompasses her take-no-prisoners approach to life. During the performance, she casually started encouraging me over the mic: ‘I like how you sing – you’re a powerful witch!’ It was a beautiful feeling. I loved how I wasn’t quite sure how it would go. With Yoko, things will never unfold in a set way.

Shortly after, she asked if I would perform Cut Piece 1964 as part of the Meltdown festival she was curating at London’s Southbank Centre. The people in the auditorium were allowed to cut off parts of my clothing with a pair of scissors. Some did whatever they wanted: they cut my hair; they stole my shoes. At the end of the 90-minute performance, I was completely naked. People see me as an exhibitionist, but I’d never been completely naked on stage before. Yoko came up to me, put a ring on my finger and kissed my hand. I started to cry.

With Cut Piece you are the object, your most vulnerable self, but you’re also causing outrage, discussion and aggression. You’re turning the mirror on the audience, and they become performers too. I remember people standing up and calling each other out: ‘Don’t touch her! Don’t cut there! Don’t do that!’ It was half mob mentality, but also people projecting onto me like I was some sort of higher power. They wanted answers from me. The work is now 60 years old, but I think it will always be relevant.

My own way of performing is very in your face. I had never been quiet or stood still on stage. I learned so much from performing Cut Piece – about how to be a loud, physical presence without moving or saying a thing. Yoko’s work is so much about generosity, giving and protest, but with a stillness at its heart. It’s the quietness that makes space for your own experience.

Peaches is a musician, producer and performance artist who lives in Berlin.

Cut Piece 1964 being performed in New Works of Yoko Ono, Carnegie Recital Hall, New York, 21 March 1965, filmed by Albert and David Maysles

Albert and David Maysles © Yoko Ono

Gina Birch

When I was in my early teens, Yoko Ono seemed pretty odd to all of us. We were mystified by this small woman who wielded so much power. I remember how badly she was received then by the UK media – but now, watching early footage of her being interviewed with John Lennon on TV in 1968, she seems fearless and full of determination to speak her truths. She was operating on a different plane, not making any concessions to Saturday night BBC chat show culture. Yoko had magic.

Her book Grapefruit (1964) gave my friends and me extraordinary short instructions that were thought-provoking in an illogical way. They tripped us up and made us smile inside. She took Zen-inspired, poetic ideas that had been outside of our experience and brought them to our consciousness.

Yoko’s performances were revolutionary in the art world. Cut Piece, she has suggested, relates to the Zen tradition of doing the most embarrassing thing you can, and seeing how you deal with it. (It has little to do with sex, despite what the British public liked to think.) In a funny way, it chimes with my early experiences in my band The Raincoats: determinedly playing and singing on stage when I had not really worked out how to do either was hugely humiliating and majorly character-forming. It has stood me in good stead – I’m not embarrassed by much.

Yoko’s music has always been challenging, boundary-breaking and, often, a beautiful assault on the ears. But she also has her tender, heart-breaking side. Her voice and lyrics are so potent, revealing her trained musical ear and poetic beauty with words.

I recently made four paintings of fearless women – my goddesses – and Yoko was one of them. In it, she is fierce, peaceful, single-minded, inventive and a disruptor. She’s magic, both good and evil, big and small, kind and fearsome – all things goddesses should embody. First, I painted her head, then I decided to dress her in her wedding dress, which gives her both strength and vulnerability. She stares back at us and dares us to feel strong.

Gina Birch is a musician, filmmaker and founding member of the post-punk band The Raincoats. Her work is included in the exhibition Women in Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970–1990, Tate Britain, until 7 April.

Bella Freud

When I was growing up in the 1970s, Yoko Ono seemed to be viewed by society – or at least by much of the media – as an enemy of the state. How dare she seduce and be worshipped by our favourite Beatle, John Lennon? Against all the malevolent backchat were photographs of this tiny, demure-looking, beautifully dressed, powerful person.

Years later, when I discovered her art and music, I realised what a genius she is, as well as being very funny. My favourite of her songs is called ‘What a Bastard the World Is’ (1973). It is a lament of tortured anguish and exasperation about being disregarded by a man. Along with furious threats – ‘Are you listening, you jerk, you pig, you bastard, you scum of the earth’ – comes ‘Oh, don’t go, don’t go, please, don’t go, I didn’t mean it, I’m just in pain’, and the brilliant, world-weary line: ‘Female lib is fine for Joan of Arc.’

I remember listening to that song, feeling rather akin. I admired her for being that raw, and it made me laugh too, in sympathy for everyone in the song. It takes a lot to write that kind of thing. Yoko Ono is never short of courage.

Bella Freud is a fashion designer whose flagship store is in London’s Marylebone.

Yoko Ono's Lion Wrapping Event, Trafalgar Square, London, 3 August 1967

© Yoko Ono. Photo: Bridgeman Images

Jojo Mehta

Yoko Ono is best known for being a disruptor. More specifically, a disruptrix – if there is such a word. A crackling, f-word glitch in art and pop: female, foreign, fearless. I have known of her since childhood and continue to be inspired by the spirit of collaboration that is a defining and impactful characteristic of her work.

Activism can take many forms. I understand it as the concrete expression of an intent to shape reality for the better: the healthier, the kinder and more compassionate, the more just. It is, in my view, the single best use of celebrity.

One example of Ono’s activism over the years shone out to me in particular: Artists Against Fracking, an environmental campaign group she co-founded in 2012 to alert New York’s governor Andrew Cuomo to the dangers of hydraulic fracturing, an exceptionally polluting method of oil and gas extraction. It felt like a kinship. Fracking was my own spur to activism and, ultimately, led to my co-founding the public campaign that became Stop Ecocide International, which is now at the heart of the accelerating global movement towards criminalisation of the worst environmental harms.

A harmonic resonance: Paul McCartney was part of Ono’s group of campaigners in 2012 and, since 2020, has also been a signed-up endorser of our work towards making ecocide a crime – work that is continuously charged by an expanding mycelium of connections and collaborations. I’d say that makes Ono a kindred spirit.

Jojo Mehta is CEO of Stop Ecocide International, a UK non-profit company advocating to make ecocide an international crime. www.stopecocide.earth

ANOHNI

Dear Yoko Ono,

Thank you for believing in me. I am sorry I betrayed you over and over. My apology doesn’t matter anymore. The only thing left now is to change my behaviour. Thank you for loving me when I was incapable of loving, when my way of loving was poisoned and deformed. Thank you for waiting at the door of my brokenness. Thank you for not giving up on me.

from, Britain

ANOHNI is a British-born musician and artist based in New York City.

Ex It 1997 at Deitch Projects, New York, 24 April - 30 May 1998

© Yoko Ono. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging. Courtesy Jefrrey Deitch

Kathleen Hanna

Yoko Ono was the first punk rock singer I ever heard, an early proponent of female rebellion in song. My parents didn’t go to college, and we didn’t have a lot of art or art books in our house, but we did have the Double Fantasy (1980) album, which had Yoko’s song ‘Kiss Kiss Kiss’ on it. My mom and I used to sing ‘Kiss, kiss, kiss, kiss me love’ around the house to each other and in the car. I was maybe 11 years old, growing up in the suburbs of Maryland, and Yoko entered my life through music.

In the late 1990s, I saw her installation Ex It 1997 for the first time. I walked into a gallery in New York City – a warehouse space with really high ceilings – and was the only person there. I saw rows of simple pine coffins, each with a tree growing where the face of the person in the coffin would have been. A soundtrack of chirping birds played over the top.

I’m sure everyone has a different experience with this piece, but in that moment, I realised that I had lost so many people over the years – from AIDS, suicide, heroin – and I had not mourned any of them. I’d just kept working, playing shows, and putting my anger and my sadness into songs. But I hadn’t really mourned until then. I didn’t have a graveyard to go to for a lot of those people that I had known, and Yoko’s work gave me my graveyard. I felt like they were all with me. This was the spirit of my chosen family surrounding me, and I saw the beauty and the hopefulness in death and rebirth.

I was in there for about an hour, and I didn’t just cry – I also laughed, and felt a million other things. Walking back to my apartment, I wondered: How the fuck can an artist do that? What a gift. I’d never stood in front of a painting and felt that way. I’d never heard a song and felt that way. I felt like I had changed when I left. It reminded me of the power and importance of art.

I think the way Yoko brings humanity and everyday life into art, making it accessible to people who don’t have art degrees, while also often being playful and funny, is what first attracted me and my mom to her all those years ago.

I now live in Pasadena, California. When everyone was shut in during COVID, I took a walk around my new neighbourhood and ended up in a little public garden. Someone had made an impromptu Wish Tree, taking inspiration from Yoko’s beautiful, hopeful idea and bringing it here at this very desperate time. That someone could do that really speaks to the generosity of her work.

The world is falling apart right now and it’s easy to feel that, as an artist, what you do is stupid. But Yoko is one of those rare artists who always reminds me: No it’s not – it’s life-giving, it’s oxygen. She just gives me oxygen.

Kathleen Hanna is a punk singer, artist, and the frontwoman of the bands Bikini Kill and Le Tigre. Her memoir, Rebel Girl: My Life as a Feminist Punk, is published in May.

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, at Tate Modern until 1 September.

Supported by John J. Studzinski CBE with additional support from the Yoko Ono Exhibition Supporters Circle and Tate Americas Foundation. Organised by Tate Modern in collaboration with Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf. Curated by Juliet Bingham, Curator, International Art with Andrew de Brún, Assistant Curator, International Art, Tate Modern and Patrizia Dander, Head of Curatorial Department with Catherine Frèrejean, Assistant Curator, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen.