Stills from Keith Piper's Viva Voce 2024

Two-channel video installation

21 mins 40 secs

© Keith Piper

CHLOE HODGE Why did you decide to take on this commission?

KEITH PIPER When the offer was made, I was thinking about the role of museums as custodians of objects and their histories, and how we can respond to problematic historical artefacts. I’m interested in the responsibility of museums to analyse, contextualise and increase our understanding of those objects, as well as extend the conversation around them. I value museums, archives and libraries as spaces in which we can encounter objects and the systems of knowledge that surround them. It’s only in encountering the object that we can begin to understand its history in all its complexity.

CH How much did you already know about the mural?

KP I’d never seen it, as it was situated in a very posh restaurant, which I couldn’t afford to eat in. I’d heard rumours about it, mostly in the context of wider critiques of Tate Britain. I was also aware of the activism of The White Pube, and Imogen Banks’s petition proposing that either the mural be removed from the restaurant or the restaurant removed from the mural room. That this work should form a decorative backdrop for the clientele of an expensive restaurant is, literally, hard to stomach. When visitors were welcomed back to Tate galleries following the lockdowns related to COVID, a decision was made to not reopen the restaurant. This, in effect, brought the room into the museum, treating the mural as an artefact to be properly examined and explored in all its problematic detail. To me, this felt like the correct decision.

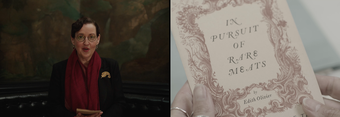

The mural itself is a panoramic narrative painting depicting a group of figures setting off from their imaginary home country of ‘Epicurania’ on a culinary Grand Tour, in search of what are described as ‘Rare Meats’. During this expedition, the group enslave a Black child, whose depiction sits at the core of many of the justifiable objections to the work, but there is also an even more problematic depiction of the child’s mother that is often overlooked. Key to what I’ve done in response to the mural is to perform a deeper reading of the work, using other examples of Whistler’s work made around the same time and extracts from a pamphlet titled In Pursuit of Rare Meats, which was written by novelist Edith Olivier with Whistler and published soon after the mural was unveiled. This helps viewers to understand and respond to the mural in a more complex and informed way.

Stills from Keith Piper's Viva Voce 2024

Two-channel video installation

21 mins 40 secs

© Keith Piper

CH Could you describe your own response?

KP The work is a two-screen video installation, projected into the centre of the room. On the screen is a drama, a verbal exchange, principally between two characters. One is Rex Whistler, or perhaps the ghost of Rex Whistler, who has been summoned back into the space by another character who introduces herself as Professor Shepherd. The Whistler character has been called up to account for the work, and the film follows their discussion as a means of uncovering the evolution of the work, its place within Whistler’s oeuvre, and its social and political context. The conversation is further punctuated by the character of novelist Edith Olivier reading sections from the explanatory pamphlet.

CH How did you come up with the idea?

KP I was struck by just how young Whistler was when he began work on the mural – still only a student in his final year at the Slade School of Art. I teach at Middlesex University, so I often speak with young artists about their practice, trying to get them to describe where their work comes from, their influences, their process and so on. At its most formal level this dialogue exists as a verbal examination, sometimes referred to as a studio critique or ‘viva voce’. I felt that staging an imagined viva voce with Whistler could be an effective way of describing the history of the mural.

Stills from Keith Piper's Viva Voce 2024

Two-channel video installation

21 mins 40 secs

© Keith Piper

CH And for that, you had to build up Whistler as a character?

KP Yes and no. That was one of the interesting conversations I had with my scriptwriter, Jacqueline Malcolm. Professor Shepherd is, in effect, our fictional stand-in; she voices our concerns. The Edith Olivier character mostly reads directly from her own writings. But the Whistler character is more complex. He is there to narrate the process by which the mural came about from a convincing ‘first-person’ perspective. However, when it comes to responding to Professor Shepherd’s observations about the racist content of the mural, it didn’t feel right to invent that. My preference is for him to ‘umm’, ‘err’ and deflect. I want the film to act like an expanded gallery label, informing the viewer about the history of the work and some of its problematic elements, but not to speculate about how Whistler might have sought to justify his work.

CH In the film, the room itself seems to sit outside of time and place.

KP Yes. Throughout the film there are hints of temporal ambiguity. For instance, when Whistler is handed the pamphlet, it’s the first time he’s seen it. He helped to write it, but it was published ten years after his death. There is also a moment in which Whistler is seen to recall the moment of his own death. The film’s characters are ambiguous, too. Take the professor: on one level, she is a contemporary art historian, researcher and academic, but on another she is able to summon historical figures at will and hold them to account.

CH Like a judge?

KP Yes, or maybe a prosecutor. I am a big fan of courtroom dramas and, of course, the prosecutor can deliver accusations directly to the accused party. I also wanted to play with the idea that Professor Shepherd could be more than this, in her ability to conjure up and cross-question a deceased artist. As an artist, I’m interested in the idea of being held to account. Imagine getting to the pearly gates and being turned away by St Peter: ‘No mate, you’re in the wrong spot! Remember all that ropey art you made? You need to head down the corridor with all the smoke and sulphur!’ At some point, we may all need to answer to the art critic in the sky, and she may look like Professor Shepherd.

Stills from Keith Piper's Viva Voce 2024

Two-channel video installation

21 mins 40 secs

© Keith Piper

CH Can you talk more about the other character in the work, Edith Olivier?

KP Olivier was a stuffy, socially conservative Victorian writer whose life, it’s been argued, was transformed through her meeting with 19-year-old Whistler and his group of friends, who have often been referred to as the ‘Bright Young Things’. Their relationship saw her flourish as a novelist, muse, and something of a mystic, although she never lost her deeply conservative politics.

CH What makes her key to the work?

KP We know that Olivier was Whistler’s close companion before, during and after the commission, but we are left to speculate how much of its content was influenced by her ideas. The pamphlet she wrote with Whistler seems to expand on the narrative depicted in the mural. People have speculated whether the pamphlet was generated in response to the mural, or if it was, in fact, a blueprint for it.

When I was developing the work, taking close-up photographs of some of Whistler’s early preparatory sketches, I made a discovery: although small, the roughly sketched figures in the drawings are annotated with names from Olivier’s story, indicating that the text predates the mural. There are also other narrative details in the pamphlet that appear in the initial sketches but not in the mural. This would seem to indicate a process of editing down the initial story, first through the sketches and then on the walls of the Tate Gallery, where scale and the pressures of time meant that other details were lost or only partially completed.

CH Do any of those lost details particularly stand out to you?

KP There is a passage at the end of the pamphlet in which the members of the expedition are rewarded on their return to Epicurania. This includes the enslaved Black child, who becomes a ‘Freeman of the state of Epicurania’, which, in itself, becomes an interesting post-colonial metaphor. However, this scene is either missing from the mural or is so incomplete as to be indecipherable. This is a point that is duly noted by Professor Shepherd in the film.

Stills from Keith Piper's Viva Voce 2024

Two-channel video installation

21 mins 40 secs

© Keith Piper

CH What else did you discover while you were researching the mural?

KP The 1920s wasn’t a period I’d really studied before. It was fascinating to look at the mural within the context of the interwar years – the political and social landscape, and the ideas that were beginning to percolate through British society. You have the General Strike of 1926, and the aftermath and paranoia sparked by the Russian Revolution. Ideas such as eugenics are widely discussed in academic circles. The Jim Crow era in the United States exports a particular brand of racism internationally through the 1915 release of D.W. Griffith’s film The Birth of a Nation, but also the displacement of Black American artists and writers spread elements of the Jazz Age to London and other cities.

CH Do you think that the mural tells us much about wider attitudes towards Black people in Britain in the 1920s?

KP I think any artwork has to be seen through the eyes of the artist that made it. Historical context is important, and I wanted to know where Whistler stood. One thing that leapt out at me is the number of images of Black people that Whistler made, especially around the time of the mural.

CH What do you think visitors will take away from your work?

KP I hope that responding to the mural can contribute to the debate about how to retain and explain difficult work. So, on the most basic level, I want visitors to take away what they would from any museum display: an understanding of the artefact as a product of its age, and, in this case, why it has become so controversial.

Stills from Keith Piper's Viva Voce 2024

Two-channel video installation

21 mins 40 secs

© Keith Piper

The Rex Whistler Commission: Keith Piper: Viva Voce is shown alongside and in dialogue with the Rex Whistler mural at Tate Britain.

Keith Piper is an artist, curator, researcher and academic. He spoke to Chloe Hodge, Project Curator and Manager, Tate Britain.