John Singer Sargent

Mrs Hugh Hammersley 1892

Photo © The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence

It’s rare – almost taboo-breaking – to see art placed alongside fashion in an institution such as Tate Britain. It’s this way: fashion, or the matter of the clothes people wear in portraiture, has been looked down upon by art curators and critics for generations. Fashion and costume are sorted into one kind of museum or department, telling their own lesser tales of social history. Meanwhile, exalted art is cordoned off to be marvelled at in higher, separate galleries. Which makes it a breathtakingly new sensation to be invited to walk into a new exhibition at Tate Britain and see the paintings of John Singer Sargent right there alongside some of the clothes that his subjects wore when he painted them.

Breaking through that old snobbish hierarchy, the exhibition Sargent and Fashion begins all kinds of revealing conversations about the ‘Age of Opulence’, the end of the 19th century and the turn of the 20th, when Sargent was working. The way in which this star of portraiture styled his subjects – the super-wealthy, celebrity performers and close friends – caused a sensation, though not always in the way his paying clients would have liked. His aim was to capture something about the sitter that was contemporary but also timeless, and frequently to set them in a historical context designed to cement their dynastic aspirations.

As a fashion journalist, what first hits me is the gorgeousness of Sargent’s technique: the way he captures the textures, colour and flow of dresses; the almost synaesthetic rustle of silk, the weighty folds of satin, the flutter of chiffon, the deep tactility of the velvet he conjures. And all that movement! Without knowing anything about how Sargent worked – or counting his references to Diego Velázquez, Franz Hals, Thomas Gainsborough, Peter Lely – you can sense how much the man enjoyed fabric. And that first impression would turn out to be on the money. As the exhibition reveals, Sargent manipulated fashion just as fluently as he used his long-handled paintbrushes to dab and dash at his canvases.

John Singer Sargent

Ena and Betty, Daughters of Asher and Mrs Wertheimer 1901

Photo © Tate

James Finch, Assistant Curator, 19th Century British Art at Tate Britain, shared with me a lovely quote from Sargent, who wrote about the painting of one of his portraits of Helen Vincent in a letter to a friend: ‘I am in the thick of dress making & painting.’ ‘There’s this idea’, Finch explained, ‘that he considers his painting as akin to a dressmaker’s craft, particularly in terms of how he’s pinning and folding the dresses that his sitters wear.’

One example of this is the 1907 portrait of his friend Lady Sassoon, painted wearing a sweeping black opera cloak folded so that its pink lining is rolled back in a diagonal across her body. It was pinned in place by Sargent, in fact. Even though we’re already in the 20th century, the jaunt of the cloak and her huge, feathered hat suggests something of the swagger of a 17th century cavalier. Her opera cloak – a sexy taffeta thing, with black lace edging the flesh-pink lining – will be displayed right next to her portrait.

Sargent was, as we might phrase it today, acting as a stylist and fashion editor. ‘The usual thing is at a first sitting to bring a box with different dresses and actually put one or two on’, he wrote in a letter to the American banker J.P. Morgan, preparing him for his wife’s sitting. These super-wealthy American women had vast wardrobes, often ordered from Paris. ‘Crowds of young American girls were brought [to Europe] to buy clothes and be presented – and with luck marry a member of the European aristocracy’, writes Philippa Pullar in her book Gilded Butterflies: The Rise and Fall of the London Season (1978). ‘Changing was an occupation which occurred at least four times a day.’ Like the girls in the recent TV adaptation of Edith Wharton’s The Buccaneers (1938), we can imagine them captivating audiences today.

John Singer Sargent

Eleanora O’Donnell Iselin (Mrs. Adrian Iselin) 1888

Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

‘Sargent’s career really follows the arc of the rise of haute couture in Paris’, Finch observes. ‘He was picking the clothes, telling them what they should have, what they should wear.’ The opportunity to parade your latest, most extravagant fashions was seen as a passport to fame and social success – almost exactly as it is for actors, musicians and influencers posing for paparazzi on red carpets and the front row of fashion runways today.

But setting up what someone was to wear before they were painted was very much Sargent’s business – and not so much theirs. Elenora O’Donnell Iselin’s ambitions, for instance, were stymied by Sargent’s interventions. Iselin came from a prominent, wealthy family in Baltimore. As Finch relates, when she commissioned Sargent, she had her maid bring down her best Paris frocks. ‘She was expecting Sargent to choose between them. But he replied that he wanted to paint her just as she was.’ She wasn’t wearing a ball-gown, but a practical, black walking dress – albeit richly trimmed with jet beading. Her portrait now reads as social documentary of late Victorian daywear, as well as revealing the character of a middle-aged power hostess. A Real Housewife of New York, circa 1888.

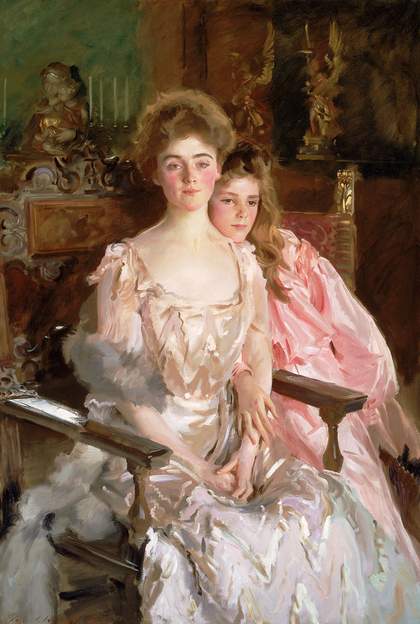

The extremely pretty Mrs Fiske Warren had a similar experience when Sargent rejected her preferred green dress on the grounds that it didn’t suit her fair complexion. Instead, he painted her wearing her sister-in-law’s pinkish dress with a lavender, zigzag-patterned skirt. Her young daughter, Rachel, leaning on her shoulder, is swathed in a piece of contrasting pink fabric that Sargent apparently draped around her. They seem to be in an ‘at home’ setting among fabulous antiques. In fact – as a photograph of that sitting shows – Sargent was working in an impromptu studio set up at Fenway Court (now the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston), freely improvising with Renaissance armchairs and an elaborate gilt candelabra.

John Singer Sargent

Mrs. Fiske Warren (Gretchen Osgood) and Her Daughter Rachel 1903

Photo © 2023 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The extent to which contemporary art was a spectator sport and the entertainment of the time is tellingly described by Edith Saunders in The Age of Worth (1954), her book about the milieu of the clients of Charles Worth – the Englishman who founded his haute couture empire at 7 rue de la Paix, Paris. After their mornings of ordering dresses, ‘in the afternoon, they would pay a few calls or visit an exhibition, drive up to the lake in the Bois de Bolougne for the purpose of displaying their fine carriages and dresses’, Saunders writes. ‘In the evenings, it was balls, dinner parties, opera and theatre.’

But as complimentary as Sargent’s work was to his show-off customers, it also had to be about his own standing as an artist. It was, after all, going to be judged at exhibitions such as the Paris Salon or the Royal Academy in London. Sargent was burned by the scandal set off by his Madame X, which he showed at the Salon in 1884. The work attracted such negative criticism that he was forced to repaint her infamous slipped dress strap. It’s the reason, it’s supposed, that he left Paris and went to live in London.

From a fashion point of view, Madame X is still a devastatingly glamorous, strong, startlingly modern silhouette; it’s arguably the harbinger of the Little Black Dress that Coco Chanel was to take ownership of several decades years later. As with all fashion that shocks, soon enough, plenty of women were wanting copies or versions of it. Though the name of the woman may someday be forgotten, the reason for the scandal lost in time, it was John Singer Sargent who created – in a sense, designed – that all-time great avant-garde fashion moment. ‘I suppose it is the best thing I’ve ever done’, he wrote when he sold the painting to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1916.

John Singer Sargent, Madame X 1883-4. Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Arthur Hoppock Hearn Fun, 1916

To Finch, many of Sargent’s greatest portraits are those of subjects he sought out to paint, not the ones who came to him wanting a commission. Sargent had to convince Virginie Gautreau, the ‘professional beauty’ who was Madame X, to pose for him. Sargent, whose own sexuality has been much debated, was drawn to unconventional people of all genders. Today he might be defined as a queer artist. His 1894 portrait of W. Graham Robertson, a friend of Oscar Wilde – to whose social circle Sargent also belonged – is a composition that, like Madame X, seems to possess a prescient kind of minimalism. The austere, dark Chesterfield coat that Sargent asked Robertson to wear is so clean, lean and vertical it might have walked straight out of a very recent Alexander McQueen or Prada show. Robertson suffered from having to pose in the heavy Chesterfield, buttoned and pinned around him during the height of a sweltering summer. We can almost feel the dense texture of its Melton wool, described in Sargent’s long, flat brush strokes. Robertson must have grumbled about being stuck in such a stifling garment, but Sargent was having none of it: ‘The coat is the picture!’ the artist declared.

Another such portrait he sought out was Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth 1889, a showstopper in the exhibition. Having attended the opening night of Macbeth at the Lyceum Theatre on 27 December 1888, Sargent was blown away by the ‘pictorial’ power of Terry’s appearance and performance. He set about persuading the actress to be painted in role. And the dress, which will be on display alongside the painting, is a full-on fashion drama.

Embroidered with green beetle wings, the dress with its medieval sleeves evoked the supposed historicism of the Scottish lay – but it’s also very much in sync with a high fashion counter-cultural movement of Sargent’s time. It was designed in avant-garde, medieval-revival style by the costume designer Alice Comyns Carr and sewn by the dressmaker Ada Nettleship, creative friends of Sargent’s at the forefront of the aesthetic movement. The craze for looking back to the Middle Ages included a portmanteau of ideas about nobility, craftsmanship, nature and, for women like the daring Ellen Terry, the liberation of flowing, uncorseted garments.

John Singer Sargent

Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth (1889)

Tate

Compared to all the swathed, pseudo-18th-century dresses, plunging necklines and bustled silhouettes that Sargent usually painted on heiresses, Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth belongs more to the liberal, artistic and politically tinged pushback against the Victorian industrial revolution represented by the Pre-Raphaelites.

‘I wish you could see my dresses!’ the actress enthused to her daughter in a letter. ‘They are superb, especially the first one: green beetles on it, and such a cloak! It is the colour that it is so splendid. The whole thing is Rossetti – rich stained-glass effects.’ Terry talks about Edward Burne-Jones, the elder member of the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood, dropping in to the studio to give Sargent his opinion. ‘Burne-Jones yesterday suggested two or three alterations about the colour, which Sargent immediately adopted.’ In Tate Britain’s exhibition, you can look between the two and see the difference between the green of the dress and the bluer cast of the painting – a decision which apparently evolved from the conversation between the two artists.

Terry’s excitement over the dress – and more importantly, how Sargent captured the essence of her role – bubbles over in her autobiography. ‘I am glad to think it is immortalised in Sargent’s picture. From the first, I knew that picture was going to be splendid’, she wrote. ‘The green and blue of the dress is splendid, and the expression as Lady Macbeth holds the crown over her head is quite wonderful. Sargent suggested ... all that I should have liked to be able to convey in my acting as Lady Macbeth.’

Sargent’s portraiture was playing its own role in the constant to-and-fro between art and fashion trends almost as soon as the paint dried. What he was doing in creating indelible public images of celebrities and performers in outrageously extravagant, sometimes shocking clothes is all the more familiar today. Think of the increasingly extreme fancy dress competition that happens every year at the Met Gala, or Beyoncé’s stage clothes, or how the Kardashians have manipulated their appearances to rise to the top of American society. Many times before that, fashion designers have made free with earlier eras to say something about the present, just as Sargent did. Christian Dior’s 1947 New Look evoked the Belle Époque; Cecil Beaton’s famous 1948 photograph for Vogue of a tableau of models in sweeping satin ballgowns in a pilastered drawing room looks uncannily like the high society scenarios Sargent created for his sitters. In this century, seen in the context of Sargent and Fashion, it would hardly be surprising if the cycle began all over again.

Sargent and Fashion, 22 February – 7 July 2024. Lead support with a generous donation from the Blavatnik Family Foundation. Additional support from the Sargent and Fashion Exhibition Supporters Circle and Tate Americas Foundation. Organised by Tate Britain and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Both MFA Boston and Tate Britain received support for international scholarly convenings and for the exhibition from the Terra Foundation for American Art. Curated by James Finch, Assistant Curator, 19th Century British Art, Tate Britain, and Erica Hirshler, Croll Senior Curator of American Paintings, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, with Chiedza Mhondoro, Assistant Curator, British Art, Tate Britain, Caroline Corbeau-Parsons, Curator of Drawings, Musée d’Orsay, and Pamela A. Parmal, Chair and David and Roberta Logie Curator of Textile and Fashion Arts Emerita, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Sarah Mower MBE is a fashion journalist and critic for Vogue.