Patrick McGrath

I was reading about Henry Fuseli’s The Nightmare c.1781–2, and I learned that he painted the picture after eating pork chops. He failed to digest them properly, had a bad dream, and the painting was his response to the dream. I think it is a pioneering work of art in that it may be one of the first to depict the unconscious mind at work – in the form of the goblin sitting on the breast of this rather abandoned woman.

Louise Welsh

Yes, it represents a very gothic sentiment – the idea of a heroine in crisis, of a woman at night in danger, in her white nightdress. And the image of the horse… the nightmare is really quite sexual and disturbing.

Patrick McGrath

It surely is. The goblin is lecherous in the extreme and then the horse is a wild-eyed creature. The woman couldn’t be more vulnerable or exposed to these twin sources of libido. It’s the libido about to ravage an innocent.

Louise Welsh

The gothic is a very sexual genre. It amuses me how often this image is used. It appears on the cover of an edition of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein I have. It’s entirely appropriate for the text. The incestuous side of the gothic is interesting. For example, Shelley’s mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, was quite obsessed for a while with Fuseli, to the point at which she went round to his house and suggested that she moved in with him. She was most put out when Mrs. Fuseli said that she didn’t really want this, and banished Mary Wollstonecraft from visiting them again. Fuseli is a very sexual artist. He makes lots of quite interesting erotic images – such as Brunhild observes Gunther hanging in Chains from the Ceiling 1807. Fuseli was perhaps self-consciously gothic, though I think his inspiration came from all different places as well as from the pork chop. Mind you, I have heard that people often ate something late at night to try to get a bad dream to inspire them. I don’t know if this is something you’ve ever fancied doing?

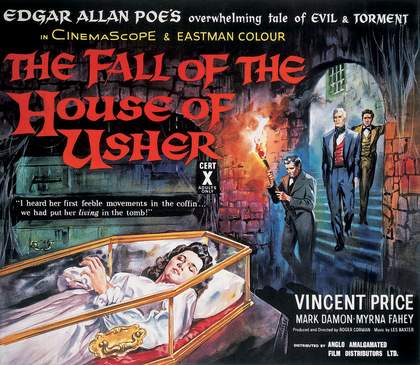

The Fall of the House of Usher 1960

Film poster

Patrick McGrath

Yes, I’ve often eaten cheese late at night so that I’ll dream vividly. I rather enjoy it. Cheese does have certain properties that act upon the neuro-physiological system to stimulate dreaming.

Louise Welsh

I am fascinated by the way our unconscious feeds into our work. Proponents of the gothic are more willing to say, like Robert Louis Stevenson: ‘I had a fine bogey dream,’ while Horace Walpole ascribed the inspiration for The Castle of Otranto (1764) to a dream. It seems to be a common thread doesn’t it?

Patrick McGrath

It does, and I suppose at that time, pre-Freud, you might be utterly intrigued with the products of your dreaming mind. And if you’re taking them seriously, as I presume nobody much did before the Romantics, you’d be discovering a tremendously rich and meaningful world in these nightly mental productions.

Louise Welsh

I’ve noticed in your work this idea of the altered state, which can be accessed through dreams, drugs, drunkenness, sexual excitement, or madness.

Patrick McGrath

I’m interested in the various mental states through which we access reality, but in such a way that we get it wrong. Dreams, drink, passion, madness – all tend to obscure the real state of things. I generally like to take characters who, at the beginning of a story, are securely occupying their own reality, and who then by way of bad habits, bad circumstances, bad luck and so on, begin to lose touch and make erroneous judgments. They find themselves drifting away from the centre, off towards the periphery. While I was researching Asylum, I read that people who go into psychiatry do so out of a fear of going mad.

Louise Welsh

The figure of the asylum is a typically gothic one, both in your novel Asylum and in its recent film adaptation. Buildings are often invested with a personality. In books or films, such as Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House (1959) or Stephen King’s The Shining (1977), the house is very much a force of evil. Recently, I went to Wigtown – a relatively unvisited part of south-west Scotland. It struck me as a very sinister place. I researched a bit of the little town’s background and found that the main site of interest was the martyr’s stake, which was where they had drowned some poor woman, a covenanter. The people nowadays are very nice, of course, but architecturally nothing much had changed in the past 100 years or so. It seemed a particularly gothic place. I wonder if old asylums, hospitals and schools that are now being made into apartments have that feeling for some people.

Patrick McGrath

Yes, it is as though suffering does suffuse the actual physical matter of these places. This must be a very old idea, because the original gothicists were far more engaged with the notion of structures having evil potential than the human mind or spirit being evil. It was Edgar Allen Poe who moved us away from physical locales as being the sites of the sinister energies and shifted them back into twisted human personalities.

Louise Welsh

Although in The Fall of the House of Usher (1839) he is still hanging on to that idea of the bloodline and the house: that when the bloodline finishes the house also fractures.

Patrick McGrath

That tale almost bridges the classical gothic to a newer psychological gothic. It’s in the minds and the behaviour of Roderick Usher and his sister that we find enormous disturbance and corruption. Yet the same is true of the structure of the building in which they live, and the climate, and the surrounding geography, the ‘black and lurid’ tarn and so on. I find with Poe that the physical surroundings serve as metaphors for what is happening within his characters.

Louise Welsh

Poe is almost using a checklist for the gothic. When you read The Fall of the House of Usher you could go down your list and think: yes, dreadful weather – tick, incest – tick, variant sexuality – tick, drugs – tick.

Patrick McGrath

It may be because so much of what we think of as the gothic originates not in Europe, but with Poe, or at least is given terrific fresh stimulus by him.

Louise Welsh

In fact it’s not confined to Europe. Japanese culture, for example, has a lot of gothic elements, especially in film. We all have longstanding, unconscious fears that are expressed through art, literature and film, and in the year 3030, if we make it, there’ll still be gothic.

Patrick McGrath

It’s extraordinary that the genre came to full flower around 1800, within about 30 years of being invented, and that it should still have energy and vitality today. I believe it’s because it does have a connection to all sorts of fears that may be born in childhood, but certainly don’t disappear with age. They develop and persist across generations and even cultures. We all have dreaming minds, and we are all capable of being terrified.

Louise Welsh

It often abjectly portrays people with physical disabilities. Think of Marty Feldman as Igor in Young Frankenstein 1973. He’s a figure of fun because he’s got a twisted back and a limp. Yet it’s also a genre that people who are marginalised feel empowered to employ. Everybody feels an ownership of the gothic. When HIV and AIDS came along, a whole new strand appeared as gay writers began to explore this terrible phenomenon through the medium of vampirism. It was a means by which we could express something that was often too painful or confusing to discuss straightforwardly.

Thomas Haywood

The Necropolis Cemetery, Glasgow 2005

Photograph

Patrick McGrath

The gothic certainly throws up broad, diverse metaphors. One of the things that characterises the genre is its peculiarly bleak relationship to time, to the past. It is very common to see the sins of the father being visited upon the child – the past working its particular power in a negative sense upon the lives of individuals of later generations.

Louise Welsh

You start the opening story of your latest book Ghost Town 2005 with a potted history, which is typically gothic. The narrator says something like, ‘as a boy I liked to wander among the tilting gravestones’, a wonderful image that signals exactly what kind of tale we’ve now entered.

Patrick McGrath

Well that one, The Year of the Gibbet, was certainly a nakedly gothic tale. I found when I was on to the second story in this collection that I’d somehow got a ghost in each, but the nature of the ghost had changed over time. The first featured a very gothic one – a good old-fashioned, rotting, smelly creature, who appears to sharpen the guilt of some poor haunted man. Maybe there is a thesis on how the ghosts we experience in the twenty-first century differ from those of the eighteenth century…

Louise Welsh

Yes, and how the signifiers – places, spaces – change as well. I have a friend who works at the University of Strathclyde. It’s a very modern building where, if you stop moving for a while, the lights go out to save electricity. She has been working late in her office and the light in the corridor outside switches on. But when she goes to investigate, the hallway is empty – pretty frightening. So we can be in the most modern place, with the most up-to-date technology, and suddenly, something unnerving happens and we’re assaulted by ancient fears. There’s a big distinction between blood, guts and gore and gothic thrillers.

Patrick McGrath

Like you, I’ve got little patience with gory horror movies. It’s much more fun to be chilled to the bone by a creepy idea than seeing a crude image of a body being hacked to bits.

Louise Welsh

Yes. Think of the difference between Anne Radcliffe’s The Italian 1797 and Matthew Lewis’s The Monk 1796, way back at the beginning of gothic. A reviewer once said that Radcliffe’s skeletons come suitably clothed, while Lewis’s jump about in terrible abandon, and a naked skeleton is about as naked as you can get! Lewis is most definitely in the horror camp, nothing is left to the imagination, while Radcliffe’s work is more accurately defined as terror. There is something lurking round the corner, and it terrifies us, even though we are sometimes uncertain what the actual object of our terror is.

Patrick McGrath

Lewis seemed already to be slightly mocking the genre, even though it was only about 35 years old. Clearly the gothic had become so richly developed that it was not difficult to write a mild pastiche of it, but also to produce a pretty grim story.

Louise Welsh

I think that’s definitely true. Gothic writers often do have a little bit of humour, because otherwise the experience of reading them could be too unremittingly grim. There’s also the obvious contrast between light and dark: a laugh can be very close to a scream, and may be all the much larger because of it.

Patrick McGrath

That’s a good point – the function of the gothic being, in part, to neutralise fears which, if they remained inarticulate, would still have potency. The minute you begin to externalise and aesthetisise these fears, you drain off their power to disturb. That is what art does in general, and what the gothic does very specifically with disturbing, unconscious material, which brings us back to The Nightmare, where the goblin and the horse seem to be threatening, in some licentious way, that poor innocent lady.

Louise Welsh

And yet she does have her eyes closed. One wonders if she is really asleep? Her pose of abandon and openness is almost inviting. This idea of tension and repression against the desire to satisfy the body is an element we see so much in the gothic – a sensibility that is very much there in the Scottish proponents of the gothic such as James Hogg, or Stevenson. For example, Dr. Jekyll is a terrible man, because he is trying to get away with his deeds by distilling the evil within himself. He’s not attempting to banish the evil, or come to terms with it. He is determined to realise his vice while relinquishing responsibility for it. He’s a hypocrite.

Patrick McGrath

Dr. Frankenstein could be accused of exactly the same thing. In both stories there’s a deep wariness of the unfettered pursuit of knowledge.

Louise Welsh

There is still very much a mistrust of scientists, especially a fear of new biotechnologies. How many headlines contain the line ‘Dr. Frankenstein’, or ‘Frankenstein Science’? People are frightened of things they consider unnatural. Perhaps this partly explains our unease with massive man-made buildings and structures, the fear of monumentalism that runs through a lot of the gothic and is a recurring theme in your work. I thought the director David Cronenberg captured that aspect brilliantly in the movie adaptation of your novel Spider with the gasworks that hang over the film a lot of the time, huge and quite threatening in a sense – that brooding structure that can be seen again in the body of the institution in David Mackenzie’s film of Asylum.

Patrick McGrath

Yes, the gasworks worked well. It had that monumentality, it did loom and it had a complicated, structural detailing within the metalwork which completely terrorized the poor brain of my schizophrenic Spider. It’s also a receptacle for gas, which has a certain odour, and here is a man who is haunted by odours, specifically those of gas, which then have a connection to his childhood and to the death of this mother. So a whole system of associations connects Spider to gas and gasworks and produced this feeling of horror. At the same time, the structure of the gasworks does have this sense of being almost a castle – you remember Kafka’s castle, how it overshadowed the village beneath? But here it’s functional, an industrial castle.

Louise Welsh

And an object that we’re all familiar with, which has been turned into something else – almost the inanimate becoming animate. I think we’ve all experienced strange moments when you glance at something and for a second you think it’s something that it’s not. Our unconscious alters an everyday object into something sinister, just for an instant. It’s almost as if the object is alive and watching us. The feeling of being observed by unseen eyes is hugely unnerving. This reminds me of the panopticon, a structure where somebody can see you wherever you are. It is an enormous source of paranoia, which we can relate to the modern world. When I walk from my house into the centre of town, I must appear on hundreds of cameras.

Patrick McGrath

And it’s easy not to see them. The extent to which we are subject to panoptical supervision is quite extraordinary.

Louise Welsh

The idea of reality TV or constant cameras is a gift to the gothic, because it plays with the notion of veracity and truth. I’ve just bought Bret Easton Ellis’s new book Lunar Park, which on the back states: ‘Regardless of how horrible the events described here might seem, the one thing you must remember if you hold this book in your hand – all of it really happened. Every word.’ I don’t know if this is a particularly gothic novel, but that is an incredibly gothic statement!

Patrick McGrath

It’s a statement which implodes. It’s the same device that any unreliable narrator employs. He says: ‘Listen to me. I’m going to tell you a true story here’ – yet that story will in the telling display its own untruthfulness, its own anomalies, its internal contradictions. As a reader you are caught somewhere in between, experiencing tension between what your sceptical reason is telling you and your desire to submit to the insistence of the narrator that this really is what happened.

Louise Welsh

I think this relates to our urge to be frightened. I don’t know why, but I’m delighted when I freak out. There are these great Japanese movies that I can’t watch unless I’ve got a cushion in front of my face. It must be some form of emotional release.

Patrick McGrath

There’s a story about Coleridge in which his little son, Hartley, gets a severe ticking off by his mother and then goes out into the garden. The poet watches him talking to some flowers in the same way as his mother has just been talking to him – he is literally discharging the imposed anger on to the flowers. Coleridge realises that poetry works in exactly the same way, and comes up with his notion of emotion recollected in tranquillity. The same is going on when we read a book or watch a film that arouses unease, anxiety and even terror in us. It’s a way to experience these emotions or discharge them in a safe place.

Louise Welsh

That makes a lot of sense. And the gothic often deals with the biggest fear that we have – death.

Patrick McGrath

And if it’s not death itself, it is aspects and characteristics of death: various states of breakdown in terms of madness, ruined buildings, moral perversity, incest, necrophilia – a movement towards a collapse of all structure; a chaos, a nothingness, which is the only way that we know of to address this thing called death.

Thomas Haywood

Staircase in the Britannia Panopticon, Glasgow 2005

Photograph

Thomas Haywood

Mannequin at the Britannia Panopticon, Glasgow 2005

Photograph

Louise Welsh

It is also a genre that appeals very much to young people. Goths are using the iconography of death, including a lot of religious artefacts. They dress in black, make their skin white and have the red lips; even the clothing might be ripped or decaying. They look fabulous and I think they really make a creative thing from the gothic. Do you see them in New York?

Patrick McGrath

The East Village is a place where punks and goths go. I find it altogether quite a pleasing look, however it’s not one I would adopt myself. Although having said that, most of us in New York, certainly below 14th Street, dress in black anyway. Black is de rigueur in great segments of the city. That may not be an entirely gothic impulse, but it’s something to do with negation, a sort of neutrality.

Louise Welsh

Do you think New York is a particularly gothic place?

Patrick McGrath

Well, at first glance you would say no, because there is not much that is particularly old in terms of buildings. They tear them down to make way for new construction. So you don’t get those sorts of structures that are imbued with the energies of sinister doings that occurred in the past. But the city does have a past. It is a place of shadows; it’s a very complex and permissive human environment. I think a lot of transgressive activity goes forward in New York. It’s not difficult to locate that vein if you want to go looking for it. There’s a fair bit of neogothic architecture too. The twin towers had these slender arches, as became so poignantly obvious when the ruined sections were all that remained after 9/11.

Louise Welsh

Glasgow, where I live, is a very gothic city. We have the huge Victorian cemetery, the Necropolis, which is a place of contrasts. It is at the very centre of the city next to the motorway and the Royal Infirmary, yet can be a very quiet spot. (The last time I went up there I saw a colony of tame deer). However, it can be a very dangerous place, and I wouldn’t recommend anyone going on their own. That contrast between monumental gravestones and statues and not quite knowing what you’re going to come across is extremely gothic.

Patrick McGrath

I’ve just written an introduction to a new edition of Charles Dickens’s Barnaby Rudge 1841, which is about the anti-Catholic Gordon riots in 1780 that left London under the control of a howling mob for six days. Dickens includes a dark gothic sub-plot about a double murder and a man haunted with the guilt. It’s a wonderful exploration of the psychology of guilt, with lots of good gothic characteristics – the place where the killings occurred is a bleak and haunted manor house. And as I was reading the various critical views of Barnaby Rudge, I came across one opinion which suggested that the great tension of the book is that Dickens has on the one hand these very topical events, while on the other he has this tale that is somehow timeless. The argument went that in the gothic you tend to move to melodrama, and that melodrama is outside of time, in that you have characters who represent very stark, moral qualities of good and bad, and who experience exaggerated emotional states and so on. Run it against a piece of historically specific narrative and you create the kind of strangely powerful tensions that hold Barnaby Rudge so taut.

Louise Welsh

Do you think part of the timelessness might be the authenticity of the gothic as well? Because you’re talking about the book exploring guilt attached to murder and we know that this is a real phenomenon. There are very few people who can commit a murder and not feel that awful guilt.

Patrick McGrath

I think that’s very much what Dickens says about this man, who has basically got away with it for years. The novel begins 22 years after the murder, and the killer is still at large. You watch Dickens describe this man, see him get into his soul, and you think: ‘Yes that’s how it must feel like if you were carrying that sort of guilt for 22 years.’ It may be that that is an aspect of human nature which is unlikely to change. Dickens was writing about an event that occurred 60 years previously, but was assuming that a murderer’s guilt looked the same in 1780 as it did in 1840. And it certainly reads in 2005 as eminently plausible. That might be a key to why the gothic continues to intrigue us.

Louise Welsh

Yes, because the idea of overriding guilt can sound melodramatic and yet when we look inside ourselves, we can see that it’s definitely something that would stay and get worse as time goes on. It is a bit like the little incubus in The Nightmare where the weight of him sitting on her chest might be the weight of guilt. The gothic is definitely a genre that allows us to enjoy our fears.

Patrick McGrath

Guilt is an insidious and eternal psychic toxin. In the gothic the best pleasures are the most subtle pleasures. You don’t really need to take an axe to somebody’s shoulder in order to feel a proper shiver of anxiety and foreboding.

Louise Welsh

Yes, now I’m quite frightened. I’ve been writing about the Britannia Panopticon, which is a music hall in Glasgow. It is in the upper storey of a big building that somehow got forgotten until it was recently rediscovered. It’s a fascinating place. They haven’t yet raised the money to do it up, but local archaeologists have been poking around under the floorboards and finding all sorts of things – buttons from uniforms from the Boer War, old theatre programmes and so on. It’s a very dark, gothic space because it has all these memories that remain untouched. The people who are looking after it have put on a quite nice display with mannequins and some dummies on the balcony, and I don’t think I’ve managed to walk in there without one of them catching my eye and giving me a huge fright – the inanimate becoming animate again.