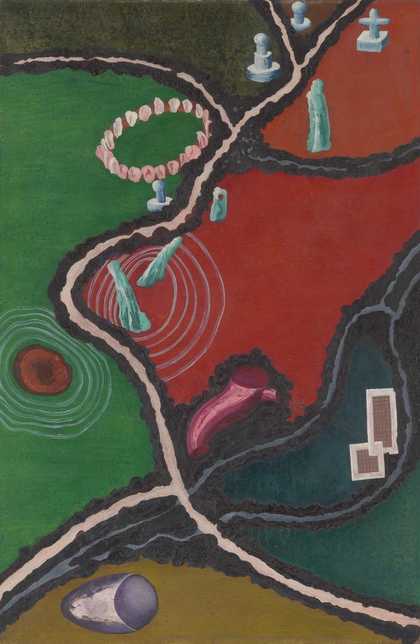

Painting made by Ithell Colquhoun's student Diana Southgate during the former's time as a primary school art teacher in 1943

Diana Southgate. Photo: Tate

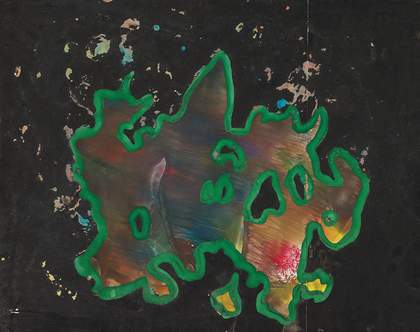

Among the many papers of Ithell Colquhoun that can be explored in the Tate Archive, one folder labelled ‘Child Art’ opens a window into the artist’s fascinating approach to teaching and making. The 14 paintings within it are all examples of decalcomania, a technique in which paint is applied randomly and then blotted to produce patterns that can be left or worked on further. Beloved of the surrealists, it is one of the ‘automatic’ techniques for painting with complete suspension of conscious control, the aim being to tap levels of the mind uninfluenced by reason. Automatism was central to Colquhoun’s artistic practice, but as a working occultist she went further than the surrealists, believing that automatically produced material could just as easily originate in the hidden world of spirits and elementals.

The paintings were made by pupils of the Damien School in Ruislip, a small private preparatory school where Colquhoun was briefly art mistress in 1943. Is it possible that she was teaching children aged between five and 11 years the rudiments of accessing the unconscious mind, or spirit possession? It seems unlikely, so a more prosaic explanation must be sought.

Painting made by an unknown student of Ithell Colquhoun during the her time as a primary school art teacher in 1943

Reserved

Colquhoun believed that automatism could help liberate the imaginative and creative powers of her students. She published an article on automatism, ‘Children of the Mantic Stain’, in Athene, the journal of the Society for Education in Art, in which she advocated its wide use in educational settings, suggesting that ‘all who find the actual beginning of a work of art a difficulty may be assisted by automatism. There is no doubt that many automatic processes can be used with stimulating effect in the teaching of art, whether to children or adults’. Automatism, in other words, provides the student with a means of getting past the intimidating, empty, white rectangle of paper, and making a start without worrying about subject matter, composition, lack of technique or other inhibiting factors. Imagination can then take over.

Painting made by Ithell Colquhoun's student D.M.K. Boland during the former's time as a primary school art teacher in 1943

DMK Boland. Photo: Tate

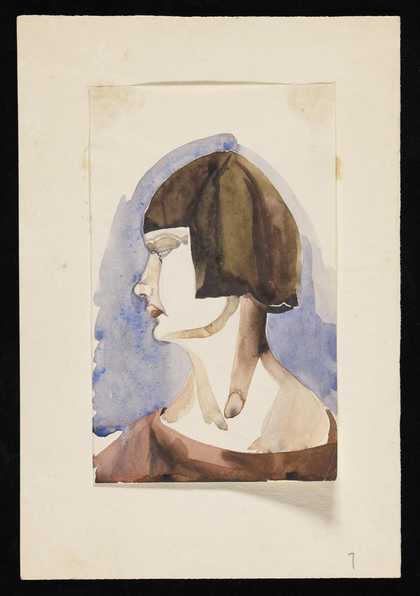

The results obtained by Colquhoun’s students were diverse. One pupil named Diana Southgate applied thick overpainting to give greater form to the blots, whereas another used heavily diluted paint to produce stains of considerable delicacy. Ailsa Crichton selected a wide range of colours and applied them with considerable vigour, while D.M.K. Boland, it seems, simply looked at the painted surface and saw a ‘Rock Lake’.

Colquhoun sent a selection of her students’ paintings to the British Council. Three were included in an international exhibition of children’s art, though precisely where these pictures were shown has yet to be discovered.

Painting made by Ithell Colquhoun's student Ailsa Crichton during the former's time as a primary school art teacher in 1943

The papers of Ithell Colquhoun were bequeathed by the artist to the Tate Archive. To discover more visit tate.org.uk/archive.

Richard Shillitoe is an expert on the life and work of Ithell Colquhoun. His recent writings include a chapter on the history of the artist’s archive in The Dance of Moon and Sun, published by Fulgur Press.