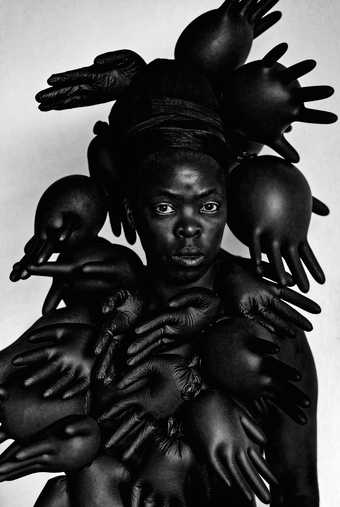

Mário Macilau

Breaking News from the Profit Corner series 2015

Archival pigment print on cotton rag paper

60 x 90 cm

In 2012, I discovered the Hulene rubbish dump, an open-pit waste site in Maputo, Mozambique, and began photographing the people who lived and worked there. More than a thousand families participate in the intensive labour of garbage collection, sustaining themselves and making a living out of whatever they find to be edible or useable amid the rubbish. Although the Hulene dump has been the source of livelihood for this informal sector, it is also the cause of major environmental degradation. With each passing day, the land surrounding the dump is polluted as workers extract valuable materials using environmentally destructive recycling methods, such as the burning of electronic waste.

One morning, I went there to shoot some pictures and spotted a broken TV on the ground. A young boy who worked at the dump pulled up behind it and asked me to take a photo of him, posing as if he were a journalist presenting the morning news. I think this picture says something hopeful about humanity, but it simultaneously shows how our planet is being destroyed by pollution and reflects how economic prosperity is distributed unequally across the globe. While countries like Mozambique are catching up, it is developed countries that contribute most to this problem of electronic waste. This boy was one of the loveliest people I have ever met, yet he was living in a site of human negligence. I don’t want people to remember these people, or my country, in this way.

Before I started to take pictures at the Hulene dump, I had believed the negative stereotypes I had heard about the people who worked there. Since then, my beliefs have been challenged. Photography can be a powerful tool for influencing change. However, this depends on how we represent our subjects, which is why I try to portray people with dignity in my photographs. In Mozambique, so much of society is hidden from view. Taking pictures of people such as those who work at the Hulene dump is where the power of photography lies – in its ability to ignite emotional responses across language or cultural barriers and give a voice to the voiceless.

I grew up in Maputo, the capital, which makes me proud on the one hand but also ashamed by the traces of colonial power still present in the city and the country at large. One vestige of this is how infrastructure is concentrated in Maputo, which has created barriers for development in the rest of the country. While I faced many difficulties in becoming an artist, it was easier for me than for those living elsewhere. I have witnessed how people in other parts of Mozambique can be shy in front of the camera. They are generally curious and want to be in my pictures, but sometimes, when they see a professional camera, they can be reminded of the Mozambican Civil War (1977–92): cameras, especially those mounted on tripods, can resemble weapons. So, my work is based on immersing myself in an environment and building strong relationships with the people I am working with. I then allow them to decide whether I can take their picture.

My photography students often ask what makes a good photo. The answer is easy: if the image was taken with dignity and commitment to social representation, then it is a great shot. When I take a picture, I don’t begin by focusing my lens. I look with my eyes, and I open my heart.

A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography, Tate Modern, 6 July 2023 – 14 January 2024. Curated by Osei Bonsu, Curator, International Art, Tate Modern with Jess Baxter and Katy Wan, Assistant Curators, Tate Modern. Supported by Tate International Council, Tate Patrons and Tate Members.

Mário Macilau is a photographer who lives in Maputo, Mozambique. He talked to Figgy Guyver.