The Operating Table by Ellie Perry

Lubaina Himid

The Operating Table 2019

Acrylic paint on canvas

152 × 152 × 2 cm

© Lubaina Himid. Courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens, London. Photo: Gavin Renshaw

She holds the weight of every walk home in the palm of her hands.

The dice, its black silhouette dotted with white, casts a shadow on her palm like a housing block at night. A series of crossroads will be unleashed as soon as she sets it down. Where to put the streetlamps? The plant pots? The bins? How does she make a safe space here? The stakes, like the housing block, are high.

All three women understand. Embedded in their anxious glances is a familiar fear. They lean into and out of each other’s ideas, tracing the red arteries of the landscape with their own unique hands, their own unique visions. The lady in orange points to the depth of the body of water. She holds her turquoise colleague’s gaze. The viewer, standing opposite the lady in blue, fills in the invisible opinions that occupy the space between them. We don’t want just to reclaim the tarmac texture of the streets; we want the pond, the trees, the dirt to be safe spaces for us too. There is more than only the threat of the women’s shadows in the background of the painting, as the turquoise protagonist leans perilously close to the lemon water jug on the windowsill, hidden from the glare of the surgical light. The latent violence, lingering within the green space laid out on the tabletop, encroaches on the broader scene. Its potency is enhanced by the fact that the women, entangled in each other’s gazes, are seemingly unaware of this potential breakage.

As we look at the painting on display in London, we remember events from last year: the two sisters murdered on their birthday, the primary school teacher killed only ten minutes’ walk away from home, the peaceful vigil met with handcuffs. All in parks. Himid painted a fear and a danger that became a topic of public debate – women’s safety.

What protective tools can be put in place? How do we fix this fragmented system of violence? Perhaps, some suggested, the overhaul starts in the design room. What would happen if women led the policymaking process over the landscapes we all share? Himid’s painting poses further questions: what if these women could debate with one another, if they had more than one opinion, more than one solution? The protagonists not only challenge the unequal power dynamics of urban planning at large, they also appear to challenge one another. Perhaps, Himid dares to suggest, there is not one universal opinion among women, even as we stride towards our shared goal.

Beyond the operating theatre, we still wait with bated breath for the possibility of the safer future that the architects hold in their hands.

Ellie Perry has recently completed an MA at the Courtauld Institute of Art, specialising in architectural history. She lives in London

Stir Until Melted (The Fortune Teller) by Katherine Birditt

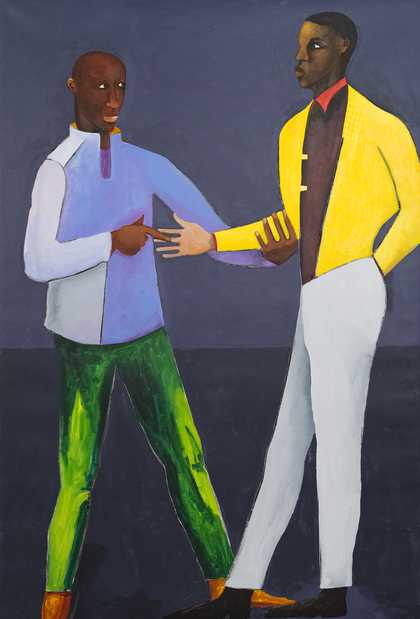

Lubaina Himid

Stir Until Melted (The Fortune Teller) 2020

Acrylic paint on canvas

183 × 122 × 2 cm

© Lubaina Himid. Courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens, London. Photo: Gavin Renshaw

In a moment of complete, unbridled honesty, I admit that I sometimes catch myself practicing my British accent. It is a performance that somehow feels necessary, affirming. As a Zimbabwean living in the United Kingdom, I have found myself reinventing and re-imagining my own identity, which often leaves me feeling fragmented and ambivalent. I stir myself into the society here, trying to melt into it as best I can so that I can build a future. Stir Until Melted (The Fortune Teller) resonates strongly with these personal sentiments. To me, it’s a kind of conversation between two figures that expands outwards to encourage the viewer to examine their own interpretations of identity, authenticity and belonging.

I think this work captures some essence of what it means to belong to the African diaspora, battling internally between what feels like authenticity and duplicity. This undertone of confrontation and conflict exists in this work, between the two figures. We witness a moment of unmasking, where identity is shaken and questioned. The figure on the left, a fortune teller, looks deeply and knowingly at the other man, his pointing finger almost accusatory. It seems to scold and, along with the grip on the arm, says, ‘I’ve caught you out in this act, in this sacrifice and sale of your authenticity.’ The other man’s hand, a central focus of the painting, looks like it belongs to someone else, perhaps from another race, which suggests that he has invested some time into trying to redefine a new self. Traditionally, the hand is often the first thing we present to someone new in an act of greeting. It is therefore unsurprising and rather apt that this part of the man is so altered, because it represents that first initial impression the world would have.

This work reminds us that identity is not some simple, well-defined entity that is fixed and static. In reality, identity is problematic because it exists in a state of constant flux, adapting continually in response to multiple forces. Somewhat paradoxically, who we are only truly awakens and exists when we interact with others, when we perform our ‘self’ for them. Accordingly, a performative space is required to frame and exhibit identity, to give it a stage so that we can begin to understand it as an entity. Performativity of the self then inevitably raises the difficult question of ‘Is there actually a real me?’ We rely on an audience to confirm our identities, to validate them. How much more so for this man in his yellow jacket, who has lived a life of blending in and becoming someone else? Has he lost or gained by this transaction? How much more vulnerable is an identity that has been shaped by a melting pot of the cultures you descend from and the ones you acquire? A Black face and a whitening hand seem to be representative of an internal conflict with identity in the diaspora.

Katherine Birditt is a second year Biomedical Science Student based in London.

Slice Ten Lemons by Eleanor Flanagan

Lubaina Himid

Slice Ten Lemons 2015/2020

Acrylic and charcoal on canvas

Two parts: 152.4 × 152.4 × 2 cm

8 × 10.5 × 3.5 cm

© Lubaina Himid. Courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens, London. Photo: Andy Keate

A woman: queen of her home, apron ablaze to light orbiting lives, glazed eyes compensating for missed sleep ... What was next? Oh yes. Slice ten lemons. A resonant tableau. A simple but proud representation of an average moment ...

This would be a perfectly credible interpretation of a different painting, but, knowing Lubaina Himid, we should probably dig deeper. Perhaps, like the violet glow beneath the lemons, another story lies behind the domesticity.

Finding this story starts, unsurprisingly, with the 11th lemon, painted onto a separate wooden block. Practically, the lemon is surplus to the recipe and so discarded. But it is more detailed than the naïve crop in the main painting and lacks their flecks of green and purple. This relative realism raises a bounty of unanswered questions. Is Himid’s human subject trapped in two-dimensionality? Is she an actress, slotted onto a stage to eternally slice lemons? Is this purgatory?

A new angle, literally, offers a clue. The sides of the wooden block, brushed with the crown’s purple, can only be seen by stepping off-centre. This boasts the three-dimensionality of the little picture and by contrast flattens the main canvas, exacerbated by the void-like charcoal table. Together with the positioning of the woodblock lemon, an alternate perspective forms: the lemons appear to be falling. What if they followed their bolder friend and tumbled right out? What would remain?

A woman: decorated fighter, armed, ready to defend. Her Christmas-cracker crown, its spikes reproduced in her blade, becomes reminiscent of the crowns that American artist Jean-Michel Basquiat used for figures deemed heroes to Black communities. Her absent stare becomes a risk analysis of the tide rising past halfway in the window, as the green curtain encroaches on its pencil line allocation and the void looms below. Many of Himid’s paintings feature windows onto the sea. Her figures party, arrange furniture, play games, slice lemons and live in joy and peace, but with the sea always a presence, intensified in Tate’s chambers where crashing waves from the artist’s Old Boat/New Money 2019 audio reverberate off the canvases.

Water follows compositions of Black families and friendships, perhaps as an allegory for lives lived in the shadow of transatlantic slavery. A moment of every picture, in luminous slashes of blue, seems to be painted in memoriam of the suffering endured by enslaved people at sea. It swells under clouds while colours catch and glow as before a storm. The painting’s hidden story is the oppressive requirement that Black people on either side of the Atlantic live with a reservoir of hyper-vigilance and intergenerational trauma rippling below day-to-day life.

Two stories are fused as one; domesticity and diasporic suffering are articulated with the same naturalistic oranges, blues and yellows: this home is a whole universe. In one of her cut-outs, Himid poses a question that echoes the one Basquiat considered with his crown motif: ‘Who are the heroes of Black people’s lives?’ The answer, according to Himid, seems to be the Black woman in all her glory, in the quotidian painted atop the generational, in the noble endeavours of the everyday.

Eleanor Flanagan is a London-based writer and student currently completing her undergraduate degree in English Literature.

The Operating Table, Stir Until Melted (The Fortune Teller) and Slice Ten Lemons are included in the exhibition Lubaina Himid, Tate Modern, until 2 October. Curated by Michael Wellen, Curator, International Art and Amrita Dhallu, Assistant Curator, International Art, Tate Modern. Supported by John J. Studzinski CBE, with additional support from the Lubaina Himid Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate Americas Foundation, Tate International Council and Tate Patrons. Organised by Tate Modern in collaboration with Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts de Lausanne/ Plateforme 10.

The Tate Etc. Writing Prize invites all Tate Collective members to respond to artworks on display at Tate. The winning submissions were chosen with Michael Wellen, Amrita Dhallu and Tate Collective Producers Tolu Elusadé, Emily Luke, Elsa Meryon, Joy Stupe, Tia Tierney and Emem Usanga.