Paul Cezanne

Sugar Bowl, Pears and Blue Cup 1865–70

Oil paint on canvas

30 × 41 cm

Listen to this article

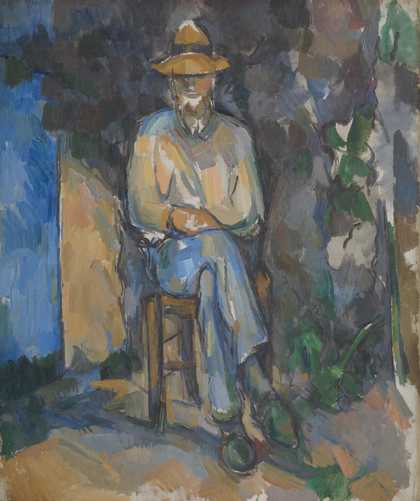

Cezanne’s paintings are still extraordinarily radical things. Seeing them in real life, it’s clear how integral the process of painting is to the build-up of the internal space within the painting. The experience of looking at them stays with you.

The paintings made in his late twenties to early thirties use an awkward and dense, gloopy build-up of white paint to give form to subjects in the paintings. In The Eternal Feminine c.1877, for instance, there isn’t a huge amount of drawing as such, but the paint takes on the forms of the subject. You could trace a lineage between that use of paint and an artist such as Goya and, earlier, Rembrandt or late Titian paintings (Cezanne’s contemporaries complained that he was a gifted painter but couldn’t draw as he avoided encapsulating figures in an outline), where the shape of the build-up of paint itself creates the subject, and not a line that illustrates the figure.

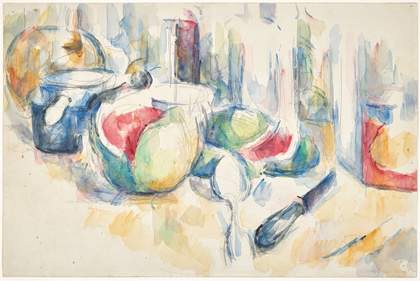

Paul Cezanne

Still Life with Sliced Watermelon c.1900

Watercolour and pencil on paper

31.5 × 47.5 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Beyeler Collection. Photo: © Robert Bayer

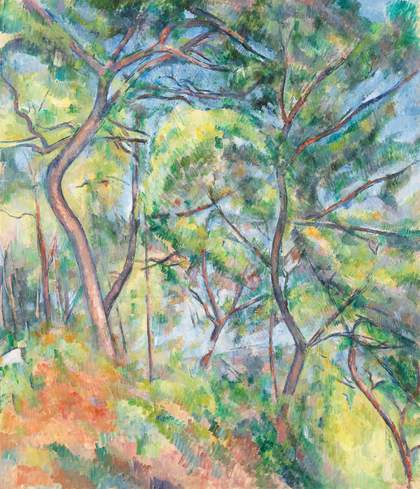

After this early period something happens, and Cezanne seems to look to Delacroix – especially for his use of ultramarine. The colour isn’t an outline in the way that an illustrative outline holds the form; the blue gives form and definition to a subject by suggesting that the subject is sitting in a different space to what is alongside it, resulting in a very strange breakdown of the picture plane. It flattens out, allowing Cezanne to use multiple perspectives through building up picture planes. This doesn’t feel like an intellectual exercise but the evolution of the painting itself.

A painting by Cezanne is not an illustration of an idea. It is the idea in its totality. There’s nothing more than what you see before you. You can say all you want about what is going on in his works, but that’s just trying to touch on something of the experience of what it’s like to be in front of them.

Michael Armitage is a painter who lives in London.

Audio narration by Wesley Nzinga.