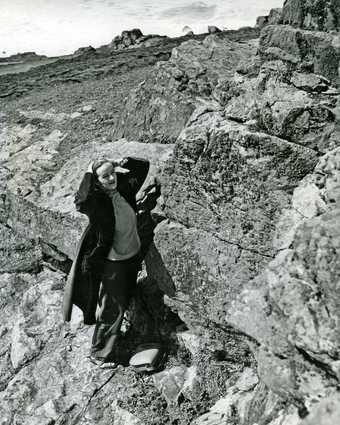

Barbara Hepworth’s bronze Forms in Movement (Pavan) 1956–9, cast 1967 at the Barbara Hepworth Museum and Sculpture Garden, St Ives, Cornwall, 1976

© Bowness

Listen to this article

Sitting in the lean-to greenhouse in Barbara Hepworth’s Trewyn Studio, lit by the bright, grey light of a St Ives rainy day, I feel a deep-rooted connection with the Cornish coast that surrounds me. I am encased within Trewyn Studio by 25ft-high granite walls that separate the studio from the stony streets. In the distance are glimpses of white sand and, above, a cacophonous canopy of birdlife.

Here I can sense life, the movement of the earth and sea, the constant coastal erosion, and the echoes of rituals and bodies in the landscape. There is a clarity of connection that leaves the senses open to encountering something fluid and shifting but also deep-rooted. It is from these roots at Trewyn Studio that new and vital movement sprang from within the works of Barbara Hepworth.

Stepping out of the greenhouse, I don’t feel like putting my raincoat on but instead allowing the rain to sit on my skin, in connection with the rainwater pooling in the contours of Hepworth’s bronze sculpture Forms in Movement (Pavan).

Forms in Movement (Pavan) 1956–9, cast 1967, began life as Forms in Movement (Galliard) 1956, a sheet-copper sculpture formed of three, fluid loops. In 1956, Hepworth began experimenting with sheet metal to create rhythmic sculptures. Galliard is a quick dance in triple time, its title suggesting an idea of continuous motion produced by the body. For me, the movement and described space of this sculpture also links to the movement of bodies within the Cornish landscape. I think especially of the expansive landscape between St Ives and Zennor, with its multiple bays that seem to stack on top of each other in interlocking compositions.

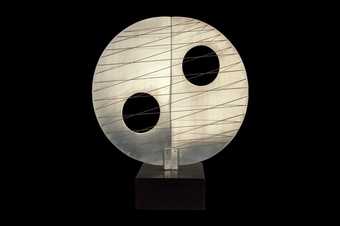

This unity of the body and the natural landscape is an idea inhabited by my recent open-air sculpture Stone (Butch) 2021, which began life as a series of experiments in direct plaster casting within fractures of natural rock formations on the Yorkshire moors, and later at Godrevy Point at St Ives Bay. This process resulted in forms that appeared to belong to both body and landscape.

The relationship between my body, material and chasm was important to me as I considered the sculptural void in direct conversation with the void we have lived with as LGBTQIA+ people due to homophobic and transphobic violence. The subsequent fracture within our experience connects with something I have described as ‘the raincoat layer’, an idea borrowed from trans and lesbian activist Leslie Feinberg’s 1993 novel Stone Butch Blues, in which a butch lesbian who has an aversion to touch is described as: ‘The most stone butch of them all ... a woman everyone said, “wore a raincoat in the shower”.’ This raincoat layer protects the body from external forces but is also part of the experience of being disconnected from the environment around us, due to being deemed ‘against nature’ as LGBTQIA+ people.

Stone (Butch), therefore, is a reclamation of natural space: a sculptural void upheld by an expanded sheet-steel figure in forward and upward motion. This movement and celebration of the Queer body within the natural elements is like dancing in the rain, and for Queer and Trans people, that dance, that unity between our true selves and the earth, is vital.

Forms in Movement (Pavan) was presented by the executors of the artist’s estate in 1980 and is on display at the Barbara Hepworth Museum and Sculpture Garden, St Ives.

Ro Robertson is an artist who lives and works in Cornwall. Their sculpture Stone (Butch) has been acquired by Yorkshire Sculpture Park, where it is installed near to Barbara Hepworth’s The Family of Man 1970.

Audio narration by Radhika Aggarwal.