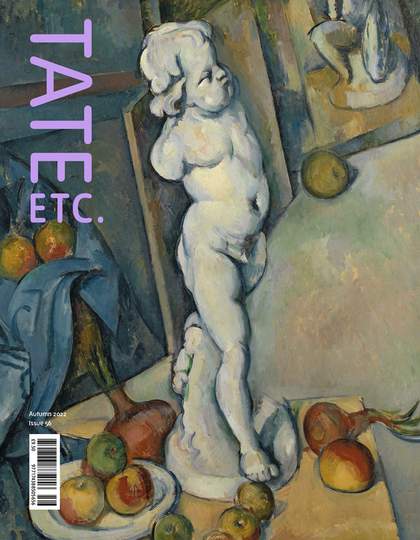

Portrait of Cecilia Vicuña, 2022

Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia. Photo: William Jess Laird

CATHERINE WOOD I’d like to start by asking you about the origins of your art. You’ve said before that you let the slow, hidden voice within you rise above your European education. Is this where it all began?

CECILIA VICUÑA My art began on a very particular day in January 1966. I was on the beach, and I could feel the wind, but instead of just blowing past me, the wind made itself into something like a knot around my body. I remember turning around, as if I had been enveloped, caressed, by the wind. And that feeling made me wonder: ‘Is it the wind doing this?’ I turned around to see the sea, the light, and I became aware that all of it was aware, and that I was being sensed like I was sensing all that was around me. And I dropped to the wet sand, and I grabbed a stick, a piece of debris, and I drew with it in the wet sand. And when I did that, I knew that I was doing it not for me but for the sea and for the elements – in other words, I was communicating with them just to say, ‘Yes, I see.’ That was the first of my art. Next thing, I began picking pieces of debris, and I created a little city. I needed to create a different kind of culture that would be erased by the high tide.

Many years went by, and one day I was looking at the abstract paintings I was doing before this event, and when I looked at them, I saw that they were the same as what I had drawn in the sand. So I had painted that before, as abstract paintings.

Cecilia Vicuña drawing in the sand on a beach in Concón, Chile, 1966

Courtesy of the artist

CW Did you repeat that drawing in the sand, or were you satisfied that somehow the imprint of it stayed in the imagination?

CV It’s hard to answer, but most likely I would already have been doing drawings in the sand regularly, but I was only conscious that this was art when I planted that stick. The sand drawings behaved like the debris objects, because neither was permanent. One wave comes and pah, it’s gone. And somehow I understood the beauty of that – the dissolution, the disappearance – because I came the next day and did it again. A moment came when I decided, ‘I will take one of these objects home, because they are so beautiful.’ I fell in love with the form, the shape of this debris.

The first debris object that I created was the spiral, and I called it A Sun. I have a photo of it. The object itself disappeared, but I wanted to recreate it because it was so important for me, because once I saw that, I had complete clarity that all this was one art form, whether it has appeared or disappeared, whether it remained or didn’t remain. That’s when I came up with the concept of arte precario (precarious art).

Cecilia Vicuña’s mixed media sculpture Guardián 1967 on a beach in Concón, Chile, which was later erased by the incoming tide

Courtesy of the artist

CW A sense of precarity was already fundamental in your first artworks, then. But the interesting shift is that you were going from making permanent paintings to making them in the sand.

CV Exactly. It’s the reverse of what you might expect. I discovered that this painting predated the drawings and objects I made on the beach. Why was that important for me? Because if we think of the history of art, we don’t know what objects did exist – let’s say, in Paleolithic times – because only a handful of things have remained, like little necklaces and things like that that are carved. So there’s no way of telling what came before – the act of painting, the art of tattooing the body, the art of painting caves or creating little carvings. Most likely it was exactly as I’m telling you now – that, interchangeably, these things were together, evolved together, and whatever shot up first is really immaterial, because they existed from the start in interaction with each other. For me, when I saw that I had made these drawings on the beach first in a painting, I felt profound happiness, because it connected my art to this ancient gesture. Now they are finding cave paintings and painted surfaces that are 70,000 years old. And I’m sure they will keep pushing this date back as more knowledge opens up. Because what I feel today, as an old woman painting, is still that ancestral drive.

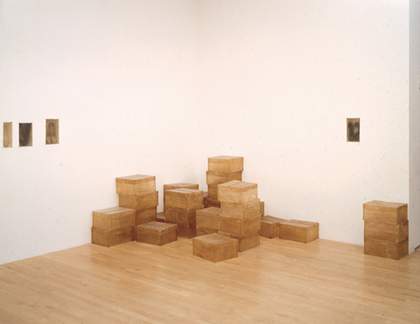

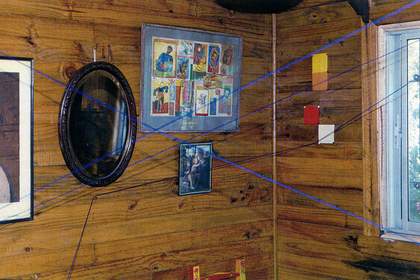

Cecilia Vicuña’s El Hilo Azul (The Blue Thread), a site-specific installation woven in the artist’s bedroom in Concón, Chile, 1972

Courtesy of the artist

CW Thinking of specific forms that might embody ancestral knowledge brings me to the quipu, which you use in your art. What does the quipu mean for you?

CV The quipu, for me, is not at all as it has been defined since the colonisation of Peru. For archaeologists and anthropologists, the quipu is basically an object: a system of communication via knots. And the complexity of the quipu keeps growing as more is understood about how much information can be encoded in the shaping of knots, the direction of the spinning, the form of twisting, the colours of the threads, and the position of the knots.

My perspective remains different. I feel that the quipu is a sort of field of knowledge or a field of energy that is so vast that the Western mind doesn’t have the tools to consider it. If archaeologists are right, the quipu is at least 5,000 years old. But it was only intensively used for the last 2,000 years before the European colonisers arrived. The colonisers let it be for another hundred years or so, but then, when they started to exploit the land and water and other natural resources, people showed up in the colonial courts with quipus as proof of their communal ownership, their duties and responsibilities towards the land. And that’s when it was banned by the colonisers. So the quipu disappeared from the colonial culture but didn’t die completely – it stayed alive among the shepherds, in highland communities, and in several forms that keep surfacing as historians dig deeper into the issue.

CW When was your moment of revelation that this was a form you could explore in your art?

CV The moment came when I was a little girl in Chile, and I came across the idea of the quipu in a book. The idea overtook me completely. It was like this field of knowledge somehow entered me, or let me in. It’s not that I learned about the quipu – it’s more like the quipu learned about me. The quipu decided that I had something to do with the quipu, and the quipu began to live in me, as image, as imagination, as desire for knowledge. So my connectivity to the quipu was a yearning for an answer to the question: ‘What was it that made this exist?’ And I never let go of that passion, that desire to learn. Event ally I began making forms of quipu that had already existed. But I hadn’t learned about them in books. I learned from them in my own hands, by making my own art and my own sculptures.

Cecilia Vicuña’s Allqa (Union of Black & White), a performance at Barnard College, New York, 1997

Courtesy of the artist

CW Could we talk about the Incan conception of the invisible quipu? How did that relate to your own?

CV For the Incas, the invisible or virtual quipu (called Ceque) was the key to the organisation of the calendar and the organisation of the irrigation systems. It was connected to the movement of water, from the summits of the mountains to the valleys where, of course, Incan cities existed. It was a concept more than a physical object; there is conjecture as to whether it was made of imaginary lines radiating out of Cusco (once capital of the Inca Empire), or if they were sight-lines, or pathways connecting certain markers. Perhaps there was nothing on the ground to indicate that the quipu-ceque existed.

CW So how was it iterated or shared?

CV The knots of this quipu could be certain sacred places that already existed, for example an important spring or a certain mountain – a certain ritual place that could be thought of as belonging to this line.

CW How incredible! And so you mean that, although it was invisible, people would describe it and talk about it?

CV Yes, and they would connect it to the stars and to the summit of the mountains.

The first quipu-like thing that I did was in 1972, when I wove my room in Concón with blue thread. The room was not that large, but it was a weaving that was, let’s say, ten times larger than my body. And the most extraordinary thing about it is that when my friends and even my family walked into my room, they didn’t see it, and that caught my attention. I thought, how interesting that this weaving is invisible to people. I wrote at the time that this weaving was connecting heaven and earth. And I said, ‘That’s the reason why they don’t see it – because they’re so used to dealing only with daily life.’

Then I began weaving the landscape. One rock to another, one side of the street to the other, one side of the river to the other. And then I began weaving people. Creating living quipus. And much later on I found that a collective ritual quipu in the 16th or 17th century was very similar to what I had been doing.

Cecilia Vicuña

Quipu Womb (The Story of the Red Thread, Athens) 2017

Wool, dye, rope and thread

Courtesy of the artist. Photo © Tate

CW How or why do you feel that you had this knowledge inside you?

CV It’s impossible to know. That’s why I say that I believe there’s something like a collective field that has been cultivated by people for 5,000, 2,000 years, or 500 years. And certain people, through their sensibility or their dreams, somehow connect to that. I cannot describe it any other way than that without distorting it.

CW So you had an instinctive knowledge of this tradition? In your body?

CV Yes. That’s why when you read in my poetry that my hands knew something but I didn’t, I mean it literally. For example, I know that I’m able to paint because, for thousands of years, people have used the hand in a particular way. You can grab a pencil as you’re grabbing it now, because it’s been millions of years – not thousands of years but millions of years – of people doing just that grabbing.

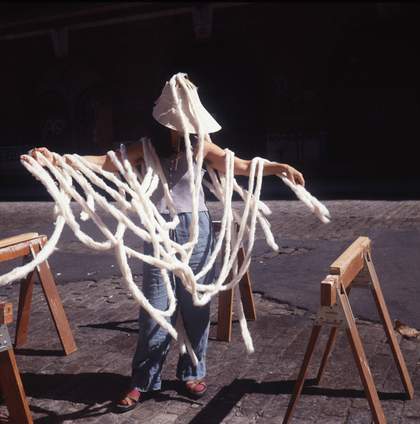

Cecilia Vicuña performing cloud-net on the street in New York, 1999

Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul, and London. Photo: César Paternosto

CV Yes. That’s why when you read in my poetry that my hands knew something but I didn’t, I mean it literally. For example, I know that I’m able to paint because, for thousands of years, people have used the hand in a particular way. You can grab a pencil as you’re grabbing it now, because it’s been millions of years – not thousands of years but millions of years – of people doing just that grabbing.

CW In the modern art world that we’re in, the story is always one of innovation and rupture: the avant-garde that breaks with tradition. What you’re talking about is tuning into ancient traditions and practices. How do you see that tension between tradition and the idea of modernity?

CV I was educated, like every artist at the time, with the idea that for art to be art it had to be a break from something that pre-existed. I knew that I should not repeat the art that I had seen. I knew, like every student would know, that it would make it not true, not real. So the search for difference was very important to me. The importance of change, of transformation, of saying something that has not yet been said is part of us and cannot be denied. But you also cannot deny that whatever you do is always a continuation. The West is interested in individuality and in signalling that one person is a genius as opposed to the others. But in truth, everything that we do responds to something that we have received and something that we’re building on. One doesn’t negate the other.

Cecilia Vicuña’s Beach Ritual (near Athens), performed at Documenta 14, Athens, Greece, 2017

Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul, and London. Photo: Mathias Voelzke

CW When you first talked about bringing quipus to Tate, you said, ‘The quipu is not entering Tate – Tate is entering the quipu.’ I’m now understanding this in terms of how you think of the quipus as a network: conceptually, materially, and socially. Could you talk about that, and about how your climate activism intersects with the quipu?

CV The quipu is a field of knowledge that has been going on, as far as we know, for more than 5,000 years. Tate Modern is only 22 years old. [laughs] So Tate is like a child compared to the quipu.

The activism that I practice is not only disregarding the thoughts, descriptions and definitions that we receive from Western domination but searching for the other thoughts and perceptions that exist in us as human beings. Because we are living proof that this universe of humanness is not what we have been told. So it relates to this Earth, because we humans are of earth. The word ‘human’ means literally ‘of earth’ – ‘of humus’, you see. If we cease to perceive that, both suffer. We cannot afford to continue this idea that language and earth, or territory and earth, are separate – because they have never been. And now you see a collective movement of artists all around the world focusing on collaborations. That is the glimmer of light at the end of this tunnel of extinction and exterminations of species, cultures and languages. And now for a huge number of young artists, thinkers, scholars, archaeologists, scientists, information technology theorisers, the quipu is back in our universe of speech and discourse, and for a very good reason.

The quipu is a guide precisely because it allows people to see themselves as interconnected – not only with the Earth but to the cosmos. So this is the kind of ecology of perception, the ecology of understanding that all of us are now in the process of shifting. In this sense, perception is associated with the moral climate of a given time, and that’s where art can intervene. Scientists all over the world have warned humanity of the impending climate catastrophe. Yet governments, banks and corporations are ignoring the warning, and are increasing investment in fossil fuel extraction, which destroys the environments that could protect the planet, such as all the world’s forests, including kelp forests, peat bogs and wetlands.

My project for the Turbine Hall intends to create pods of interconnected action and exchange between the creative forces of art, science and communities that seek the preservation of the world’s climate. That’s where Tate and the quipu are coming together – because the quipu wants and needs Tate as much as Tate needs and wants the quipu. That’s why you and I are working on this.

Hyundai Commission: Cecilia Vicuña, Tate Modern, 11 October 2022 – 16 April 2023. Curated by Catherine Wood, Director of Programme, Tate Modern, and Fiontán Moran, Assistant Curator, International Art, Tate Modern. In partnership with Hyundai Motor.

Cecilia Vicuña is an artist who lives in New York and Santiago. She talked to Catherine Wood. This is an edited extract of a conversation in Cecilia Vicuña, published by Tate Publishing.