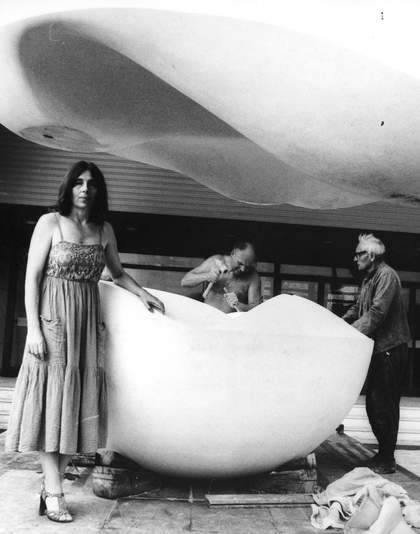

Maria Bartuszová and assistants setting up the artificial stone sculpture Metamorphosis, Two-Part Sculpture at the newly built crematorium in Košice, Slovakia, 1982, photographed by Gabriel Kladek

© The Estate of Maria Bartuszová. Photo © Gabriel Kladek

Listen to this article

In 2012, I travelled to Maria Bartuszová’s (1936– 1996) studio in Košice, a remote south-eastern corner of Slovakia. The town was developed in Communist-era Czechoslovakia as one of the country’s key cultural and industrial centres. Young people from Prague were incentivised to resettle in this remote area, where new work and housing opportunities also attracted the young artist Maria Bartuszová and her husband, sculptor Juraj Bartusz. After finishing their studies at the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague, they moved to Košice in 1963, where Bartuszová was able to secure commissions for public designs and outdoor sculptures as part of the programme for cultural modernisation in the city.

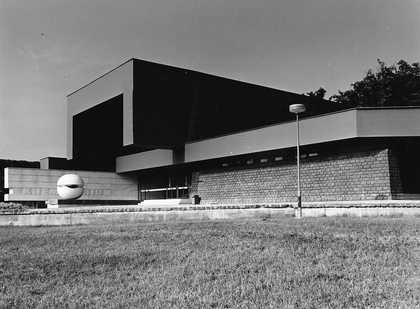

After passing through the old town, still rich with Habsburgian grandeur, I came across various sites where Bartuszová had left her mark: abstract reliefs adorning modern buildings, plaques and door handles – a complete repertoire of municipal commissions given to artists in the Communist era to extend and promote the aesthetics approved of by the regime. But one site stood out: in front of the town’s imposing brutalist-style crematorium stood a spherical, white form with an organic-looking incision parting the top half from its solid bottom, like a cell mid-division. Bartuszová’s Metamorphosis, Two-Part Sculpture 1982 looked like an otherworldly entity that had just landed on the doorstep.

Metamorphosis, Two-Part Sculpture installed at the crematorium designed by architect Pavol Merjavý in Košice, Slovakia, 1982, photographed by Alexander Jiroušek

© The Estate of Maria Bartuszová. Courtesy the Estate of Maria Bartuszová, Košice, and Alison Jacques, London © The Archive of Maria Bartuszová, Košice. Photo © Alexander Jiroušek

Working in relative seclusion, Bartuszová took inspiration from international modern sculp- tors mainly through art books. The clean organic abstraction and provocatively androgynous figures created by Romanian-French sculptor Constantin Brancusi became modern archetypes for the young Bartuszová’s own biomorphic minimalism. Brancusi’s Bird in Space – inspired by a Romanian folk- tale of a mythical golden bird that tells the future and cures people of their blindness – would prove to be a poetic foreshadowing of her own social engagement through her art.

Maria Bartuszová

Homage to Fontana II 1987

Plaster relief

150 × 120 × 30 cm

Grażyna Kulczyk Collection. © The Estate of Maria Bartuszová. Courtesy the Estate of Maria Bartuszová, Košice, and Alison Jacques, London © The Archive of Maria Bartuszová, Košice. Photo © Michael Brzezinski

Bartuszová was also able to follow the new inter- national art movements through magazines such as Flash Art. A testament to her encounter with the Argentine-Italian artist Lucio Fontana was her large plaster relief Homage to Fontana II 1987. With blatant humour, she appropriated his signature incisions and perforations of the canvas by cutting a slit into the smooth surface of her piece, through which a breast- shaped volume protrudes.

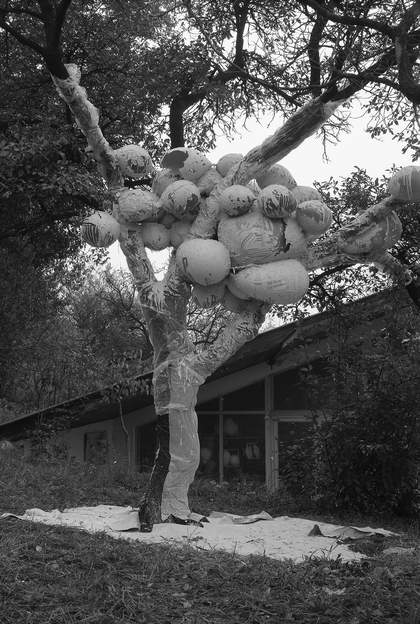

Meanwhile, the artist’s suburban studio, nesting on a hillside, its modern architecture surrounded by an overgrown garden, became a site where Bartuszová investigated the structures of natural life, exploring systems of germination and growth. In 1987 she created the installation Tree, in which the branches of a plum tree appear to have become the target of a large growth of plaster ovoids. A site-specific development of Bartuszova’s plaster formations titled Endless Eggs 1985–6, the works in this series can be read as abstract manifestations of cycles of nature, without end or limit.

Maria Bartuszová’s Tree 1987, consisting of a plum tree, plaster, string, plastic, foil and paper, in the artist’s garden in Košice, Slovakia, photographed by Gabriel Kladek

© The Estate of Maria Bartuszová. Photo © Gabriel Kladek

Suspended from the ceiling of her studio, a large cluster of these oval forms with their countless cavities and voids still asserts itself. Created by the artist using a technique she developed in the 1980s and 1990s called ‘pneumatic casting’, these hollow forms were made by pouring plaster over inflated balloons. The resulting paper-thin plaster shells are perforated and broken, almost as if impacted by a disaster. This structure of fractured ovals looks as though it has grown exponentially, as might a prolific organism, but its ruined appearance also conveys a state of melancholic temporariness. Could this be an allegory for the failed social utopia of the Communist era? Or an expression of the apocalyptic threat felt during the late Cold War period?

Maria Bartuszová

Endless Egg 1986

Plaster

30.8 × 40 × 30.5 cm

Untitled 1984

Plaster

11 × 13.1 × 9.5 cm

Untitled 1986

Plaster

19.4 × 19.8 × 19.7 cm

© The Estate of Maria Bartuszová. Courtesy the Estate of Maria Bartuszová, Košice, and Alison Jacques, London © The Archive of Maria Bartuszová, Košice. Photo © Michael Brzezinski

Bartuszová saw her work operating as ‘symbols of relationships between people’. She was also keenly interested in early childhood development, experimenting with a new vocabulary of arrested fluid forms that resembled bodily features in an abstracted, ‘pre-symbolic’ state, and the search for unstable and ‘aimless’ forms as an expression of the beginning of psychic life. Human relations stood in the centre of Bartuszová’s pedagogical interests, too. She believed that art was a universal communication tool and sought to extend her practice into educational territory by working with and for children.

Maria Bartuszová clearing snow off the slide at the kindergarten on Sládkovičova Street in Revúca, Slovakia, 1970

© The Estate of Maria Bartuszová. Courtesy the Estate of Maria Bartuszová, Košice, and Alison Jacques, London © The Archive of Maria Bartuszová, Košice

Between 1964 and 1970 she created designs for children’s playgrounds; all but one of these – the Children’s climbing frame and slide, Kindergarten, Sládkovičova, Revúca, Slovakia 1970 – remained unrealised. The spheric plaster form of her Model, Children’s Climbing Frame 1964 looks like a giant shell or an exotic plant. Created as a protective zone, a functional environment designed as a pleasure ground for children, this object at the same time appears like a futurist form temporarily absorbing human activity before it hovers on to new destinations. This outlandish association is further nurtured by a photomontage Bartuszová created in which the spheric model is staged in dramatic twilight and surrounded by three childlike figures who could equally be Martians embarking on a spacecraft. Another model for a children’s climbing frame from 1964 looks like an adaptation of Alberto Giacometti’s intimate avant-garde plateaux reimagined for parkour – abstract modernist forms providing genuine capacities for a new type of human relations.

Maria Bartuszová

Model, Children’s Climbing Frame 1964–5

Plaster and wire

20.5 × 23.4 × 25.3 cm

Model, Children’s Climbing Frame 1964

Plaster and wire

22.2 × 36.2 × 26.5 cm

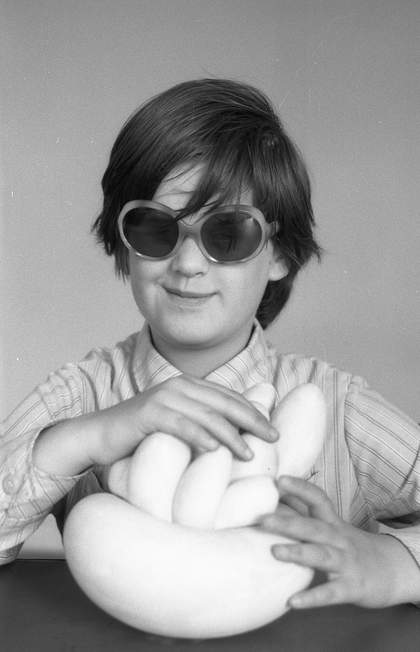

All of these propositions speak of a particular sensibility – of tactility, compatibility and fluidity. These were also characteristic of the vocabulary of organic forms Bartuszová created in her ‘assembly kits’, used in workshops that she designed with art historian and photographer Gabriel Kladek for blind and partially sighted children in the 1960s and 1970s. For the Institute of Blind People and the Elementary School for Blind and Partially Sighted Children in Levoča, Slovakia, the artist invented modular pieces made of plaster and bronze that were designed to be ‘didactic classroom aids’ for ‘orientational haptic exercises’. She hoped that these sets, which bore a strong resemblance to her early sculptural forms, would offer the children an aesthetic experience and help to develop their imagination. Kladek’s extraordinary photographic documentation of the First and Second Sculpture Symposium for blind children at the Elementary School for Blind and Partially Sighted Children in Levoča in 1976 and 1983 also shows children touching, holding and tracing their fingers over pieces such as Bartuszová’s plaster Folded Figure V, Haptic 1967 and aluminium Folded Figure VII, Horizontal, Haptic 1975.

First and Second Sculpture Symposium at the Elementary School for Blind and Partially Sighted Children, in Cooperation with Gabriel Kladek, November 1976 and June 1983, Levoča, Slovakia, photographed by Gabriel Kladek

© The Estate of Maria Bartuszová. Photos © Gabriel Kladek

I have always been fascinated by the futurist drive of women avant-garde artists who, as a consequence of the ‘invisibilisation’ inflicted by their mainstream modernist contemporaries, were rendered, in writer Paul B. Preciado’s words, ‘extemporary ... contemporary to no one’. Though she worked in relative isolation during her lifetime, Bartuszová’s dynamic experimentation with different materials and techniques of making, her visionary educational and public artworks, and her pioneering formal concerns blending gender, sexuality and the natural world with the language of abstraction, have ensured that her art continues to touch us to this day.

Maria Bartuszová, Tate Modern, 20 September 2022 – 16 April 2023. Curated by Juliet Bingham, Curator, International Art, and Dina Akhmadeeva and Beatriz Cifuentes Feliciano, Assistant Curators, International Art, Tate Modern. Supported by the Maria Bartuszová Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate Americas Foundation, Tate International Council and Tate Patrons.

Anke Kempkes is an international curator, art historian and critic with a focus on avant-garde women artists and queer modernity. She is Lecturer at Zurich University of the Arts.

Audio narration by Wesley Nzinga.