Ibrahim El-Salahi

Reborn Sounds of Childhood Dreams I (1961–5)

Tate

During the days I spent recently at Tate Modern looking at the Sudanese artist Ibrahim El-Salahi’s Reborn Sounds of Childhood Dreams I 1961–5, Sudan’s democratically elected government was overthrown by a military coup. The unrest excited old divisions in the country and there was fighting and shooting in the streets. A friend of mine, who had dropped everything and moved back to Khartoum in order to work for the now ousted administration, was not answering her phone. All my attempts to reach her failed.

Ibrahim El-Salahi was born in 1930 in Omdurman, on the opposite bank of the Nile from Khartoum. He studied art and won a scholarship to London’s Slade School of Art. On completing his studies, he returned home and confidently exhibited his new paintings. But it did not go very well. The public was neither moved nor engaged by his work. It was irrelevant to them, and these were the people El-Salahi cared most about.

This marked a turning point in the young artist’s career. He travelled across the country with his sketchbook. The experience made him all the more determined to find a way to combine developments in contemporary European art, to which he remained committed, with his Islamic, Arabic and African heritage. The tones and colours of the Sudanese landscape, the features of the people and the forms of Arabic script all began to find their way into a new kind of vernacular abstraction. He was quickly becoming one of the Arab world’s most promising young artists.

But then, when he reached his early forties, El-Salahi put his career on hold in order to serve his country. He became a diplomat and later worked in the Ministry of Culture and Information. In 1975, a wave of government crackdowns on civil society saw the arrest of several artists and intellectuals. El-Salahi was imprisoned without trial for six months. Shortly after his release, he left the country, eventually settling in Oxford where he continues to live and work today.

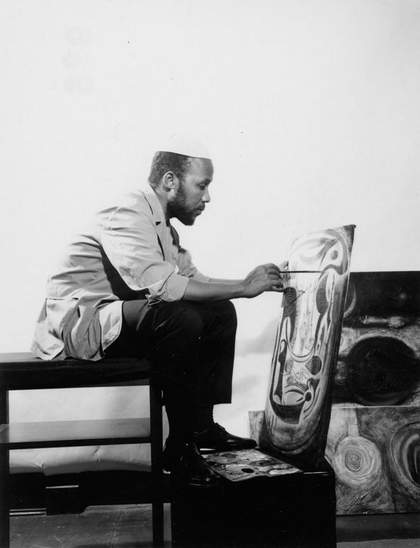

I met him once in London and was taken by his directness and humility. He spoke about how all he needed to do to make work was to allow himself to become susceptible to the demands of the painting, to the ideas and images that arise subconsciously in the work.

‘You start with a nucleus and let it grow. How it grows, you have no control over it. It controls itself.’

His trust in this mysterious process was strangely matter of fact, and yet what he was saying arose from a philosophical and spiritual tradition, one having to do with his interest in Sufism and the idea of being lost in contemplation, and the belief that surrender to craft, movement, and the making of patterns and calligraphy could lead to deeper meditations on the nature of being and the divine.

We spoke about his late friend Tayeb Salih, a Sudanese novelist whom I admired and had read closely in my youth, and who had also ended up in the UK. When I asked El-Salahi how they first met, his face lit up. They had been small children, playing football, and someone kicked the ball far away. The two happened to run and fetch it.

‘We met by that ball,’ he said and laughed softly, almost inwardly. ‘That was how it started, and we became friends and loved each other from then on.’

Friendship is important to El-Salahi. He is a man of genuine warmth, an artist who suffered exile and, perhaps for that reason, is deeply marked by social ties. When you are with him, you cannot help but detect the quiet and sincere ways in which he is enlivened by the presence of others.

Reborn Sounds of Childhood Dreams I initially came out of the failed attempt to paint a picture together with a friend. El-Salahi had been working as a teacher at the art college in Khartoum. He and one of his friends had secured a long strip of cloth – a precious commodity. The idea was to collaborate on a larger picture, but this was soon abandoned, and the two artists decided to split the material between them. El-Salahi glued his two pieces together to form a large square canvas, about 2.6m square, giving the surface a patched and mended quality.

I wonder what became of his friend’s attempt, whether that was to be Reborn Sounds of Childhood Dreams II? If so, that would explain the picture’s attendant quality, the way it appears to be waiting, almost listening out, for its companion.

If Marguerite Kelsey by Meredith Frampton, a painting I wrote about in the previous issue of this magazine, was in part about looking and being looked at, El-Salahi’s early masterpiece is a picture concerned with the implications of listening and being listened to, overheard, witnessed, while remaining a witness, in a world in which our fates are vulnerable to one another’s actions. Even the eyes here, by turns constricted, focused or bemused, are hindered by the ear’s effort to concentrate, to catch what might be said. I have always found this curious about Reborn Sounds of Childhood Dreams I, but never more poignantly than during these times.

The picture is divided into two areas: a white sky above, and beneath it a procession of ghostly forms standing in a row. The sky is far more intricate than it first appears, not white at all, in fact; it is doing all it can to contain what is behind it – the yellows and ochres and the spinning galaxies – making it clear that the characters below are witnessed by the heavens. At first these figures appear as an impediment, but then they come to seem more like a visitation, a party of doubtful and doubting spirits, busy with questions. As well as being ephemeral and passing, as temporary as all mortals, they also seem to benefit from a foundational history, a cultural depth that is derived from an unbroken lineage. There is a tension between this and the picture’s contemporary sensibility, as though the painting is asking how to be both modern and rooted.

These visitors form a sort of society, emerging before us with their needs and expectations. The two dominant figures are perhaps the emblematic parents. They are murmuring commentary to one another and seem unsure what to make of us. Beneath them are dark regions with swirling and morphing moons, script, eyes and openings, heads that appear as totems of passion and regret, the sudden attentive pause of a bird listening, the mangled memory of an utterance trapped in its mouth. There are skeletons that are structures of the living, but also the memory of the dead. There is a powerful vitality to all of this, as though what is being reported here, and what is occurring before our eyes, is as natural as night or the movement of blood in veins, or the reoccurring elaborations of a childhood dream, which is also the dream of childhood, of innocence and possibility.

When you stand close to Reborn Sounds of Childhood Dreams I, you become uncannily aware of what you might say, as though you are placed under its demand somehow. And although you are, of course, reading it with your eyes, your ears too are required. The surface is a field of transmission. Its textures, layers, colours and the strangely natural manner in which its unnatural forms all reside on the canvas hint at the disorientating historical terrain that El-Salahi has had to navigate, obliging him to consolidate what at first might seem inharmonious: east and west, Africa and Europe. In this regard, he brings to mind figures such as the Algerian-French novelist Assia Djebar, the Palestinian-American author and theorist Edward Said, and the Jamaican-British cultural theorist Stuart Hall: women and men of a similar generation who had to quickly find a new language with which to address the violent legacy of colonialism and chart a course through a complex and fragmented present.

The last time I left the gallery, I tried again to reach my friend in Khartoum, and on this occasion I got through. She was at home with her family, all doing their best to remain calm and hopeful. She described the chaos and confusion that had taken over the city. She sounded exhausted and heartbroken. She said, ‘If only they gave us more time, heard our plea.’

Reborn Sounds of Childhood Dreams I is on display at Tate Modern. It was purchased from the artist with assistance from the Africa Acquisitions Committee, the Middle East North Africa Acquisitions Committee, Tate International Council and Tate Members in 2013.

Hisham Matar’s most recent book is A Month in Siena, published by Penguin, which was in part inspired by a piece he wrote for Tate Etc. on a painting by the Sienese artist Giovanni di Paolo.