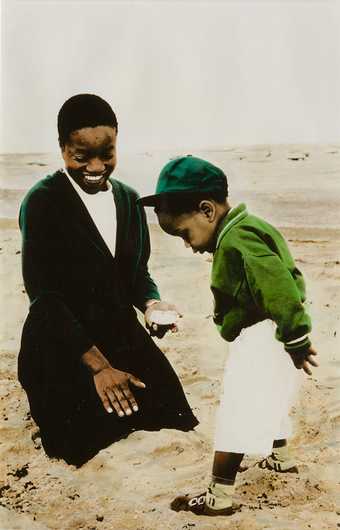

Ingrid Pollard

Oceans Apart 1989 (detail)

11 hand-tinted gelatin silver prints on paper with text

62.8 × 52.5 cm (each)

© Ingrid Pollard. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2021

DAVID A. BAILEY Nature has great significance in Caribbean literature and art, and the sea has particular resonance – something that Derek Walcott captures in his poem ‘The Sea Is History’ (1979). Alberta and Isaac, could you describe the role of the natural world, particularly the sea, in relation to your art?

Video still from Alberta Whittle’s You Can Never Touch the Same Water Twice 2017

© Alberta Whittle. All rights reserved, DACS 2021. Courtesy the artist and Copperfield, London

ALBERTA WHITTLE I spent much of my upbringing by the water’s edge, living very close to the ocean. There was always this sense of connectedness to its spirit but also the lingering question – how did we arrive here? What are the extended histories behind my family’s rootedness in the Caribbean? Consequently, when I arrived in the UK, I found myself longing for the ocean and trying to unpick how my presence was being framed; whether I was in a sense returning, and if I belonged here.

My digital collages, sculptures and film work are grounded in my curiosity about the ocean’s symbiotic relationship with arrival and departure; and beyond this, about the knowledge hidden beneath the water’s surface in the intertidal zone and deep waters. What resides in that archipelago of the Caribbean, and how can we connect more meaningfully with the diaspora?

The ocean is a place of deep mystery – a graveyard, but also a healing zone. When I am in the ocean, I feel at times that I’m creating a deeper connection with ancestors who may have lost their lives in the Middle Passage, and also with those who may have taken refuge near the ocean in Barbados. It feels both insistently haunting, as well as a place to go and baptise myself afresh. The sea can take on these different meanings.

In many of the images used in my digital collages, I return to a particular waterway in Barbados on the west coast, supposedly the site of the British arrival in Saint James – Jamestown’s original naming. I do so with an almost ghostly feeling, but also with an understanding of my own mortality, the mortality of my ancestors, and of what transpired in these watery zones.

What do I take with me from this body of water when I’m in Britain? Britain’s been my home now for over 20 years – which feels quite miraculous, frankly; that I am still here, still alive.

Isaac Julien’s Paradise Omeros 2002 installed at Documenta 11 in Kassel, Germany, 2002

© Isaac Julien. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro, London/Venice

ISAAC JULIEN The oceanic is a recurring motif or theme in my work. My connection to it relates to my own family history – both my parents were from Saint Lucia. Filming there to make Paradise Omeros 2002 was like returning to a primal scene, and to the sea as a kind of primal space. It bears trauma but also possibilities, and also translates those lives and archipelago stories into a bigger story for the 20th and 21st centuries – one based around movement and subjectivities.

Paradise Omeros is a three-screen video that delves into the fantasies and feelings of Créolité (or creoleness) – the mixed language, the hybrid mental states and the territorial transpositions that arise when one lives in multiple cultures. Its protagonist, Achille, appears in two time periods and locations – first working as a waiter at a beach resort in contemporary Saint Lucia, and later wandering through the grey brutalist buildings of 1960s London. It was pivotal for me, in that it was in direct conversation with Derek Walcott, whom I met during Documenta 11’s Platform 3 workshop on Créolité and Creolization, held in Saint Lucia in January 2002.

In his Nobel Prize-winning poem Omeros (1990), he recasts Homeric mythology around the Caribbean, and I tried to re-articulate this in my own work. Walcott’s incredibly important poem ‘The Sea Is History’ also figures in the work – not literally but visually, in that I was interested in the way in which the Atlantic was being evoked, and to make that a passage for my protagonists in the work, as well as to create the flow between the islands – between England and Saint Lucia.

The natural world is a central theme in the way it reinscribes the body and relates to the question of movement; and also to the submerging and translation of identities and how they’re renewed in that transition. Paradise Omeros is also about the Windrush generation; for example, in the party scene we hear The Paragons’ song ‘The Tide Is High’, and during that moment, the important questions of home and belonging and of resistance come to the foreground.

Several of the works I made around that time drew on contemporary debates about Creolization and Créolité, terms originally discussed by writers such as the Martinique-born Édouard Glissant. They were about decentring and refocusing on the Caribbean as a site for thinking about the ways in which artists were making works in that part of the world, and also how literary, poetic and theoretical influences from the Caribbean were beginning to take hold in the contemporary art world.

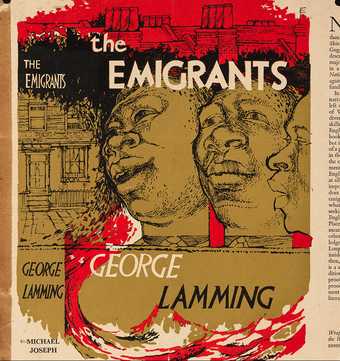

Dust jacket of George Lamming’s novel The Emigrants (1954), featuring illustration by Denis Williams

© Estate of Denis Williams

ALEX FARQUHARSON Alberta, in your work there is also a strong sense of connection and dialogue with poets and writers, particularly in relation to the oral tradition and the power of the voice: one of your videos in the exhibition is titled A study in vocal intonation 2018. An important aspect of Life Between Islands is its dialogue with Caribbean literature – poetry, novels – but also theory and history, because so many of these literary writers were also historians, anthropologists, cultural theorists, and even philosophers, such as Sylvia Wynter. Could you talk about how you use the word in your work, and which writers and thinkers have especially inspired you?

AW When I first started to make film work, I found myself consistently responding to poetry. In fact, one of the first film works I made was a collaboration with my dad, and it began because I was deeply moved by one of his poems, ‘My Land’ (2001). And growing up in Barbados, I was always highly aware of Kamau Brathwaite’s writing. I was fortunate that, through my parents, I knew him and his widow, Beverly, well. He cast a long shadow in Barbados, even when he was living in Jamaica and New York. In particular, it was the way he spoke about ‘nation language’ and created such an important distinction within my understanding of identity and place, between the language that you spoke – language for the streets – and language for school; country language versus town language. I grew up close to town, so I spoke town language.

AF He meant ‘nation’ in a different way from how we tend to mean it in the UK, didn’t he?

AW Absolutely. He meant ‘nation language’ in terms of how we consider our Caribbean, Barbadian vernacular language. He really valorised it and developed a striking dynamism in how he visualised language and text on the page, which I always found impressive and inspiring. There is a sense of percussion and a rhythm, almost like a heartbeat, whenever I read Kamau’s work. Working with text became a way for me to create my own score in conversation or communion with poets, writers and thinkers that I greatly admire, like Kamau. Particularly his ‘Kumina’ poem, where he speaks about the grief of losing his stepson. My interest in ‘Kumina’ prompted a departure point in my work, because it really started making me think about how the poem expressed love, loss and grief in a textual style that is read so visually and could be felt so much through the body.

Zak Ové

La Jablesse 2013

Mixed media including beached tree trunk and branches, vintage mannequin, vintage African mask, beached rope from the Thames, brass horns and trumpet and a necklace of antique nails

36.5 × 51.1 cm

© Zak Ové. Photo: Will Amlot

When I read Kamau’s poetry, or work by writers such as Christina Sharpe or Sylvia Wynter, I hope to extend my individual understanding of my own humanity in a way that collages these ideas together. Collage has such a deep presence in my work as an extended artistic method. When I was hearing Isaac speak about Créolité, I found myself thinking of collage as a form of Créolité in terms of layering and rupturing of form, such as image, text or sound.

Isaac, when I think about your film, Paradise Omeros, what always comes to mind is the image of the solitary man on the beach and his signification as an oracle-like figure, and also the way he speaks directly to ideas of return, dislocation and citizenship. Often when we think about the Caribbean or the Caribbean diaspora, we don’t actually consider who was left behind and how fracturing this can be. Paradise Omeros inspired so much of how I think about my own work – how to listen to those within the diaspora in the Caribbean in tandem with myself, living in Britain. Your work also reminds me of Caribbean people building community in Britain, building families. In my work, I hope to build theoretical communions with other artists, writers and poets through their work.

Christina Sharpe’s work on ‘the wake’ is such an inspirational force. Her use of the term ‘the wake’ becomes a mode of addressing different ideas under the spectre of the afterlife of slavery, where premature Black death is anticipated and normalised. The wake becomes the trail in the water that a ship leaves in motion, a place to come together and look after the dead, while simultaneously the wake of a gunshot. Within my practice, I adopt this premise of ‘the wake’ and also ‘wake work’ as an invitation to come together to work through racialised understandings of humanness, and also to nurture self-compassion. When I was developing You Can Never Touch the Same Water Twice 2017, Sharpe’s theories also became a means of connecting with wateriness.

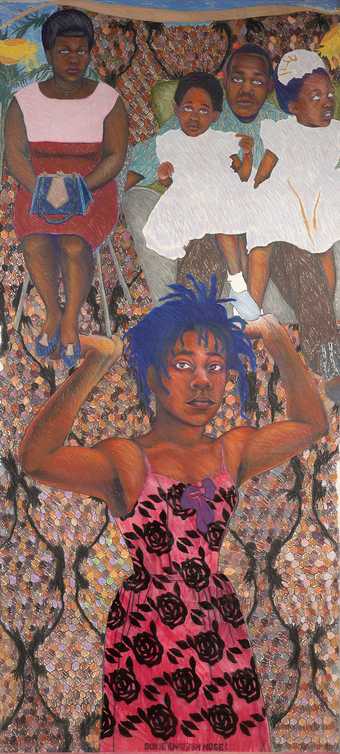

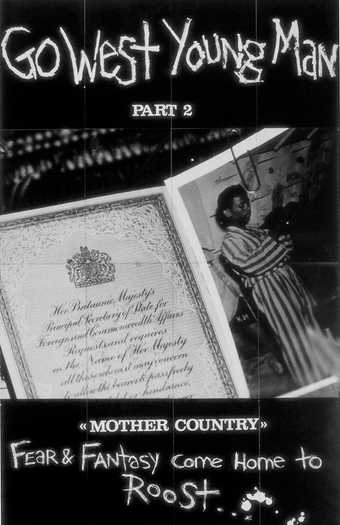

Keith Piper

Go West Young Man 1987 (detail)

14 gelatin silver prints on paper mounted on board

84 × 56 cm (each)

© Keith Piper

DAB On the notion of connection, you both use split screens in your work. How important is that to getting across the message about diaspora aesthetics, translatability and movement from one situation trans-Atlantically to another?

IJ What I was trying to achieve in Paradise Omeros was an oscillation effect between movements, between the Caribbean and Britain. In the loop of the film, this oscillation throws my Homer protagonist against the question which gets replicated throughout the film – that of globalisation and movement, symbolised in the representation of the silver football. I was really interested in both the resonance of that effect and what has been produced through those movements, how they’ve reconstituted ideas around identity and made contributions to literature, poetry and theory.

Alongside those ideas in the work, I was also interested in the way in which one could try to create a subject that inhabited these identities without it being like a pathology – a double consciousness, I guess – and working with multiple screens allows you to transgress time and location. I think that was what attracted me to the effects of montage and bricolage – effects that are also in earlier works like Territories 1984, where there is a layering using different transitions of images and collage. What I was trying to articulate in those works was the syntax of the language in relationship to ideas around Créolité, and how this could translate into artistic and cinematic forms.

Video still from Alberta Whittle’s A study in vocal intonation 2018

Alberta Whittle. All rights reserved, DACS 2021. Courtesy the artist and Copperfield, London

AW Well, prior to making films I made sculptures which were mostly assemblage or bricolage works. When I started making films it was always very much from a sculptural perspective, with that feeling of layering, of ghosts. So much has been obfuscated and erased, especially what we understand about the Caribbean. I wanted to play with what was revealed and what was hidden.

I often feel a bit like a duppy [a Jamaican Patois term used in several Caribbean countries to mean a ghost or spirit], because, so often in my work, I perform this role – a ghosting, a haunting of history. In my films, I make moving collages on screen, and this becomes another way of revealing the ghosts that are lingering, trying to come forward. I think so often about the novel Feeding the Ghosts (1997) by Fred D’Aguiar, another writer/poet who has deeply influenced me. His idea of giving hospitality to ghosts is a way of thinking about how we build accountability and knowledge, as well as empathy in how we work through the legacy of racialised slavery. Unfortunately, history is too often presented in a binary way – British history, Caribbean history, and never the twain shall meet. For me, that is ridiculous.

When I make my films now, and make aesthetic choices like a split screen, it’s very much about making work for both ghosts and the living – offering the audience and ghosts hospitality; it’s a bit of an invitation. But, as Isaac said, it is also a way of working with time, of thinking about histories and understanding that this moment of current protest is really an enduring, exhausting moment that has been going on since long before the Windrush generation.

In a work such as A study in vocal intonation, I create layers that speak of both recent and older histories. I literally appear in the film as a duppy in the main gallery space of the Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) in Glasgow, a space built by a tobacco merchant who had plantations in the Caribbean, which later became the Royal Exchange. This is a place that happens to be in the centre of Glasgow but is deeply connected to the Caribbean, to different parts of Africa, to the Americas. This is an interlinked history and a reckoning with how we all are situated today. So when I am literally ‘haunting’ that gallery, I am telling the viewer that the structures that we dwell in, and see art in, are entrenched in ghostly colonial histories just beneath the surface, and that we must all engage with these histories for our own healing.

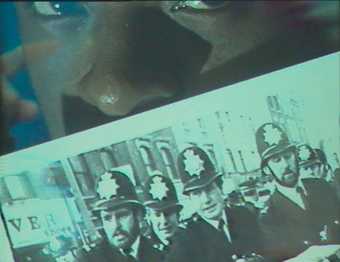

Film still from Isaac Julien’s Territories 1984

© Isaac Julien. Courtesy the artist

IJ Alberta has spoken about the question of collage, and I spoke about the bricolage effect. In a work like Territories, the power of sound and music counterpoints the visual montage strategy. Using visual alliterations and echoes – of questions of rupture and desire, the gaze and policing – and bringing these into motion under the impact of dub aesthetic, the film should be encountered as a remix. Its repeated phrases, oscillations and orchestrations depart from reggae. To present all of these territories, which were fluid and in contestation, one had to transgress the materials – Super 8, video, 16mm – while foregrounding the sonic interventions into the work.

AF The significant differences between the first and second generation of Caribbean immigrants or emigrants in Britain is apparent in the work of both of you. It’s important in much of the exhibition, and is so often played out through the image of the home and how it’s represented. What is the role of the family and of the relationships between generations – between the ‘arrivants’ as Brathwaite called them and the ‘rebel generation’, as Linton Kwesi Johnson called the second generation – in your work?

IJ In Paradise Omeros, it’s really about the question of xenophobia and xenophilia – the hatred of the other and the love of the other – and how that gets internalised and then restated through the two protagonists. There’s the disavowal of the Creole language – you could say a colonial hatred of it – and then there’s, if you like, the question of Eros and the desire of the other, which is a very big tension in the Caribbean in terms of questions around masculinity and sexual identity.

The question of intergenerationality is an important one, because, when we think about the early Caribbean émigré artists that came to Britain, the history of their contributions were seen in dialogue with Western art traditions. To a certain extent, they were very misunderstood, and only recently have their contributions been viewed as belonging both to British art and to diasporic aesthetics. It took a long time for people to reconcile the kind of map paintings that Frank Bowling was making with the work of all his diasporic contemporaries, such as Aubrey Williams, who were involved in similar languages.

How these aesthetics have been both acknowledged and brought into our own practices has been part of an intergenerational journey of recognition of those interventions. But there has also been a kind of productive tension as well. In early works like Territories, there was a deliberate break in trying to critique some of the dominant discourses that were being produced at that time by one generation of documentary filmmakers, towards the kind of works that we wanted to make, which were more invested in the semiological reading of Black cultures.

Of course, there’s always the connection, always the trajectory, and that becomes very interesting in an exhibition such as this, which joins these different methodologies and practices intergenerationally and shows, not how these elements can be tested against one another, but what that joining produces; we’ve never had that opportunity before, or at least it’s been quite rare.

Ada M. Patterson

Looking for ‘Looking for Langston’ 2021

C-type print on paper

© Alberta Whittle. All rights reserved, DACS 2021. Courtesy the artist and Copperfield, London

AW Talking about intergenerational relationships makes me think about plotting ancestral relations alongside family testimonies and their role in one’s understanding of place and community, as well as deeper, contested histories. In the last few years, I’ve worked quite closely with my family and often interweave shared family lore in my work. The work Road Openers (For E) 2019 was inspired by my grandfather, who was a Barbadian architect. He travelled to the UK in the sixties but decided to return home to look after his family. That work is very much concerned with him as someone cosmopolitan who moved around the world; he lived in Europe, in Israel, and in the UK before moving back to Barbados. I wanted to look at what cosmopolitanism, transit and belonging meant in that time, but also to acknowledge my grandfather’s creative practice and pay homage to him as someone who supported his children and grandchildren in their creativity. Growing up in a household where art was always available to me meant that making became a big part of my everyday life.

When I see the breadth of artists selected for Life Between Islands, from Keith Piper to Vanley Burke to Ada Patterson, I think about my work as being in communion with these Caribbean elders and contemporaries. I feel the tremendous pull of multiple generations and the potential resonance of situating my work alongside these artistic genealogies, which, prior to this, I have never experienced. There is a great joy about this intergenerational recognition, because it creates a dreaming space for remembering those who’ve passed on, those who are running beside us, and how we can create communion with them.

AF We have already asked you about the role of the past, history, the ancestral and memory in your work, and it is fascinating how the use of the past by you and others – intellectuals, musicians, other artists – also evokes the future. Caribbean thought and expression are so rich in this idea. Stuart Hall touches on this when he talks about taking ‘detours through our pasts to produce ourselves anew’.

AW I love that Stuart Hall quote. When I am pursuing a new body of work or looking back at pieces I’ve made – in particular You Can Never Touch the Same Water Twice – there is this sense of breaking images apart, unlearning their coding and reading, and then attempting to piece them back together into something completely different or adjacent to its original meaning – something that tries to speak of a queer futurity, which is also deeply speculative.

At one point in the film, I describe my tongue as a selector, a phrase echoing dub and dancehall, which I grew up listening to. My tongue is literally Anglicised and there is loss in that realisation of embodiment of colonial power, but also a desire to speak through deeper, non-linguistic connections with pasts and futures – and a sense that this conflation of feelings can be articulated, chewed over in a rupturing of images and ideas through collage or montage.

Processes like collage offer a space for remaking ideas and remaking future selves. In the Caribbean, many creative practices often follow a deep reflection of where we all fit within the world today, and what we choose to take with us from the past. And also how we can re-articulate our understanding to create new knowledge. My current work claims these ideas of making home and making new selves for the future.

DAB Beautiful. Isaac, I can’t help thinking very literally of the silver football rolling in the surf in Paradise Omeros. It seems to be such a futuristic image...

IJ The silver ball is an incredibly good metaphor – the way that it transports itself between Saint Lucia and London between screens. It is an inanimate object, an image of globalisation, that transgresses geography and, in a way, time, too.

Life Between Islands: Caribbean-British Art 50s – Now, Tate Britain, 1 December 2021 – 3 April 2022. Supported by the Deborah Loeb Brice Foundation, with additional support from the Life Between Islands Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate Americas Foundation, Tate Patrons and Tate Members. Research supported by Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational in partnership with Hyundai Motor

David A. Bailey is a photographer, writer, curator and lecturer who lives and works in London. He is co-founder and Artistic Director of International Curators Forum and co-curator of Life Between Islands.

Alex Farquharson is Director of Tate Britain and co-curator of Life Between Islands.

Isaac Julien is a filmmaker and installation artist who lives and works in London.

Alberta Whittle is an artist, researcher and curator who lives and works in Glasgow.