Editor's Note

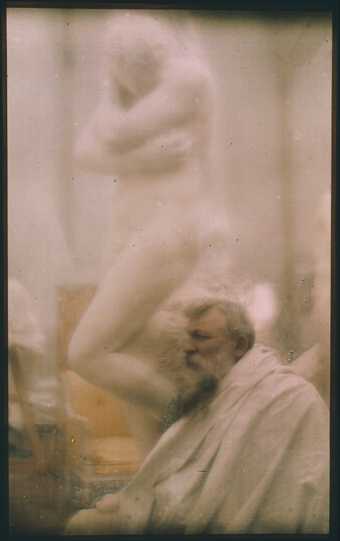

On the cover:

Edward Steichen

Rodin - The Eve 1907

Autochrome

15.9 × 9.8 cm

We are delighted that our doors are open again, allowing you to explore the fantastic range of exhibitions and collection displays this season.

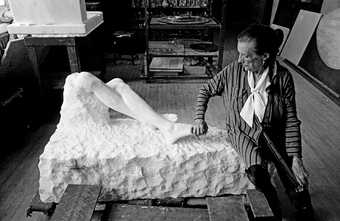

On the cover of our summer issue we print the extraordinary image of Auguste Rodin photographed in 1907 by Edward Steichen, showing the artist wrapped in drapery and sitting at the base of his plaster model Eve. Several years earlier, after recently arriving in Paris, Steichen had visited Rodin’s groundbreaking exhibition at the Place de l’Alma. There, rather than showing his bronze or marble sculptures, as might have been expected, Rodin purposefully displayed his life’s work almost entirely in plaster, foregrounding the idea of the ‘artist’s hand’ at work.

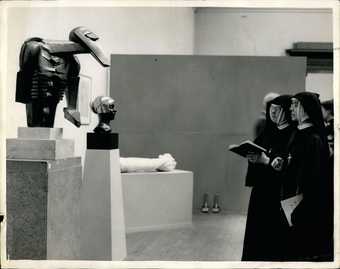

The EY Exhibition: The Making of Rodin at Tate Modern is the first exhibition to focus closely on Rodin’s use of plaster and should be a revelation to many – not least because it gives us a fascinating insight into the dynamics between the artist and his models and collaborators; among them were fellow sculptor Camille Claudel, the Japanese actress Ota Hisa, and friend Helene von Nostitz.

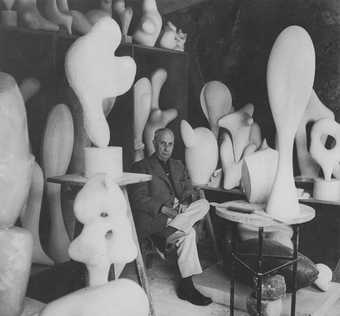

The spirit of collaboration and shared ideas also permeates the work of Sophie Taeuber-Arp, whose first UK retrospective comes to Tate Modern this summer. Collaboration was important to the dada movement in which Taeuber-Arp began her career, although she later pursued a quieter aesthetic revolution around abstraction with her husband and chief collaborator Jean (Hans) Arp. Her output was diverse – encompassing paintings, embroidery, sculptures, magazines and puppets – and it blurred the boundaries between traditional crafts and modernist abstraction.

At the time, there was a collective idealism to both of their work, as Arp would recall in later years: ‘We humbly tried to approach the pure radiance of reality … We wanted our work to simplify and transmute the world and make it beautiful.’

Nowadays this modernist approach has developed beyond simple notions of beauty to embrace a more inclusive, collective approach that reflects the rich diversity of cultures, ideas and ideals. As always, art has a role to play here, as Joseph Beuys knew well. Beuys, who co-founded Germany’s Green Party, understood, for example, that culture and climate are inextricably linked to politics and social change. He also understood that indigenous wisdom is the key to understanding how to help shape the future. You can experience for yourself how Tate’s collection is part of this conversation in displays such as A Year in Art: Australia 1992, which reaches back 65,000 years and explores the important idea of custodianship in contemporary art today. This, and many other collection displays, are on view across our four sites this summer. Welcome back!

Simon Grant