Sir Stanley Spencer

The Resurrection, Cookham (1924–7)

Tate

I was born into a clerical family, and by the time I was eight years old, I was already a chorister at Winchester Cathedral. I am convinced that it was this start in life that, perversely, led me to an eternal appreciation and huge enjoyment of Stanley Spencer’s work: it is at once exhilaratingly irreverent, thrilling, rewarding and beautiful.

It was on a day off from my choral duties at the Cathedral that my episcopal father took me to Cookham, Stanley’s hometown, where the artist had set many of his paintings. Outside the door of his studio sat the telltale shambles of a perambulator. This was Stanley’s painting chariot, which had seen so much of the action in the neighbouring churchyard where he painted. Lying in the pram were an array of objects: a torn umbrella, a decaying easel, paint cloths, and the battered paint pots and brushes that had been party to his work. On entering this almost threadbare school-room studio, a questioning candle was lit in my youthful head, as well as an abiding love for Stanley’s work.

In preparation for this visit, my father and I had seen Stanley’s enormous painting The Resurrection, Cookham 1924–7 at Tate Britain. I had absolutely revelled in the fact that Stanley had woven real people into the graveyard scene. Some of those he depicted were living villagers, rising out of tombs in their own Cookham village churchyard. Some were dead people, well known in the village, wrestling to escape their graves.

My father pretended he was scandalised by the painting. I absolutely wallowed in it. All this stuff about going to heaven – or hell – fell away. I realised Stanley was telling me, in no uncertain terms, that we are all destined for the earth. All the ceremonies, cassocks, and ruffs of choral life faded as these temporal figures stalked the graveyard. I found it provocatively and hilariously rude, but profoundly beautiful too. I didn’t forsake religion completely, I just felt open to questioning much of it. And naturally enough, I felt drawn to Spencer for life.

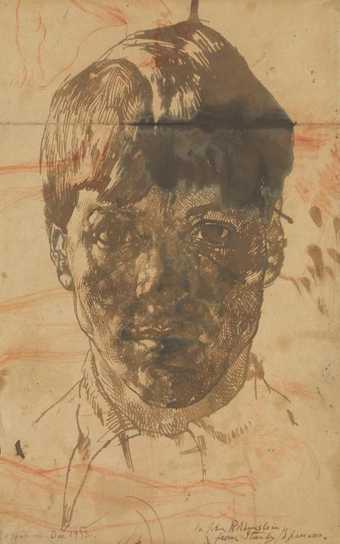

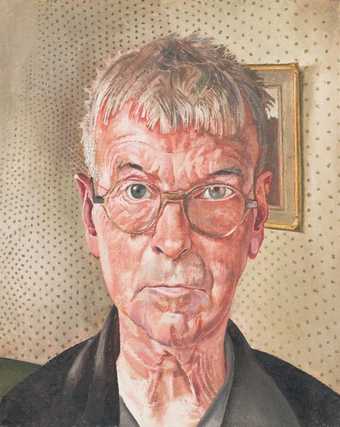

Sir Stanley Spencer

Self-Portrait (1959)

Tate

© Estate of Stanley Spencer. All Rights Reserved 2023 / Bridgeman Images

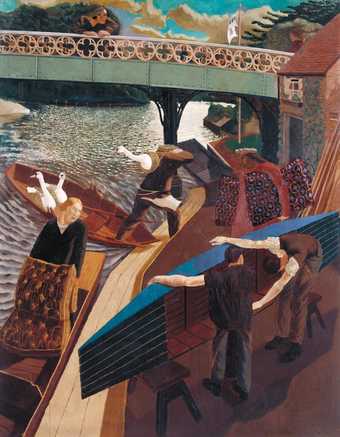

I was aware of the existence of the Spencer feast that is the interior of the Sandham Memorial Chapel in Burghclere, but did not visit until I was in my late 30s. The exterior of this First World War memorial (dedicated to a single soldier who had died in the fighting in Thessaloniki) has the appearance of a local authority crematorium, but the interior was to blow my mind. Stanley painted every inch of each wall in extraordinary detail. Scattered crosses and dead horses dominate the great East wall. On another he portrays an officer reading a map on horseback, contriving a brilliant perspective that enables us to both look up at the face of the officer on his horse, and down at the map he is reading, laid out across the horse’s back.

But if there is one painting at Burghclere that speaks to Spencer’s extraordinary technical skill it is Reveille 1929. In this panel, mosquito nets hang from the roof of an army tent and he manages to almost photographically conjure soldiers as seen through the unpaintable fabric of the nets – a veritable painting miracle. I’ve probably visited Burghclere a dozen or more times. Once, quite by chance, I found Stanley’s daughters there, showing a couple of friends around. Unity, a painter, talked readily of her father, adding an extra flourish of eccentricity to

what we already knew of Stanley. Shirin, her musical sister, was shy, more reserved, and stayed in the background. But in a strange way, meeting them in their father’s special place added to my overall sense of connection with Stanley.

Spencer’s work is intensely personal – a vivid portrayal of life as he saw it. He was never shy about presenting people as his eccentric self perceived them. My relationship to his work has infected my own modest efforts, although, in truth, I am more drawn to landscape. Although in life I am a ‘people person’, I find painting humanity very challenging. Seascapes, countryside, yes – but humanity, particularly as closely as Spencer observed it – that is a true challenge.

I can’t wait to visit the latest Spencer display at Tate Britain. It includes three self-portraits, each saying that bit more about who he was. Two of them were painted in his 20s. The last, which I like to describe as craggy, was painted in 1959, the very year he died.

A selection of work by Stanley Spencer is on display as part of Stanley Spencer, Tate Britain, until 19 September. Curated by Elena Crippa, Curator, Modern and Contemporary British Art, Tate.

Jon Snow was a Trustee of Tate from 1999 to 2008 and Chair of Tate Members Council from 2010 to 2019. He has been main presenter of Channel 4 News since 1989.