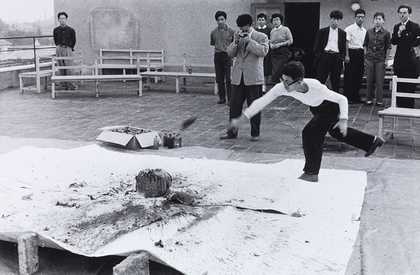

Otsuji Kiyoji documents Shimamoto Shōzō throwing glass bottles of colourful pigments against a stone at the centre of a canvas, 2nd Gutai Exhibition, Tokyo, 1956

© Seiko Otsuji / Courtesy of Musashino Art University Museum & Library, Tokyo Publishing House. From the portfolio Kiyoji Otsuji GUTAI PHOTOGRAPH 1956-57

In December 1956, the Japanese artist Yoshihara Jirō wrote a manifesto for the Gutai group. Its first lines declare:

To today’s consciousness, the art of the past, which on the whole presents an alluring appearance, seems fraudulent. Let’s bid farewell to the hoaxes piled up on the altars and in the palaces, the drawing rooms and the antique shops.

Gutai – officially known as Gutai Bijutsu Kyōkai (Gutai Art Association) – was founded by Shimamoto Shōzō and Yoshihara in Osaka in 1954. Shimamoto came up with its name: ‘gu’ meaning tool or a way of doing something, and ‘tai’ meaning a body – in other words, the physical embodiment of an idea.

Ranging in age from their mid-20s to late 40s, the 15 original members of Gutai were part of a generation that had experienced first-hand the unimaginable horrors of the Second World War. Like the dadaists, who protested the First World War with their brilliant absurdist performances at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich four decades earlier, the members of Gutai were fierce in their insistence that history had failed them, and that cultural and societal change was long overdue.

In a country attempting to recover from militarism, art was Gutai’s weapon. Freedom of expression was paramount to the artists, and the group was insistent that theirs was an art form without rules: their community was focused less on promoting a group mentality than on nurturing the creativity of the individual. Their stated aim was to rise above the ruins of the past and to embrace possibility in order to discover new, imaginative forms in which, according to their manifesto, ‘human spirit and matter’ would ‘shake hands with each other while keeping their distance’.

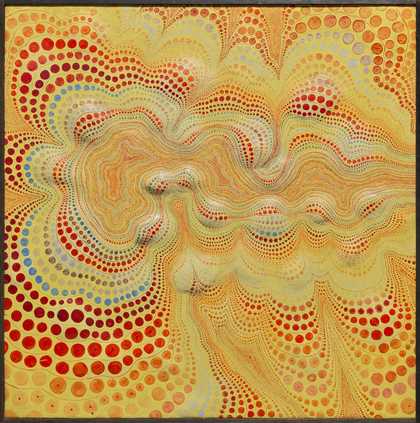

Minoru Onoda

WORK62-W (1962)

Tate

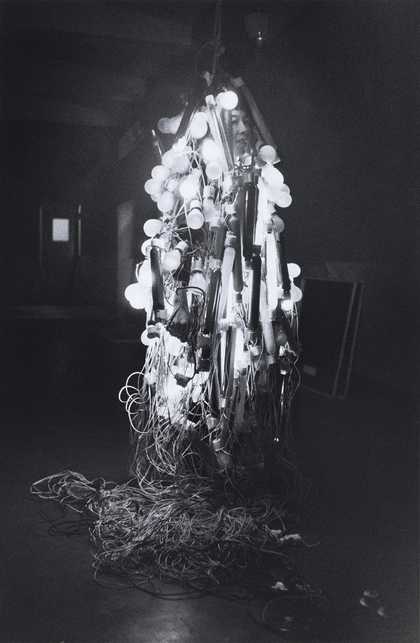

Gutai celebrated what was ‘fresh’ and ‘newborn’, and that which ‘went beyond abstraction’. Shiraga Kazuo swung from a rope attached to the ceiling in order to paint canvases with his feet; Shimamoto packed paint into a small cannon and shot it at a large sheet of canvas; Yoshida Toshio burnt paintings and made artworks from shadows, watering cans and soap foam; Tanaka Atsuko wore a dress of blinking, hand-painted light bulbs; Yamazaki Tsuruko displayed 25 dyed tin cans along the floor; and Murakami Saburō repeatedly burst through large sheets of paper that he had fixed to wooden frames. Process was as important to the group as a finished product – as much a symbolic gesture as it was a way of working.

Otsuji Kiyoji’s photograph shows Tanaka Atsuko wearing her Electric Dress, made from electrical wires and painted neon light bulbs, at the 2nd Gutai Exhibition, Tokyo, 1956

© Seiko Otsuji / Courtesy of Musashino Art University Museum & Library, Tokyo Publishing House. © Estate of Onoda Minoru, photo © Tate. From the portfolio Kiyoji Otsuji GUTAI PHOTOGRAPH 1956-57

In the 1960s, second- and then third-generation Gutai artists included the ‘3 Ms’: Mukai Shūji, who painted enigmatic symbols; Matsutani Takesada, whose airfilled vinyl shapes were inspired by gazing into a microscope; and Maekawa Tsuyoshi, who created abstract paintings from burlap. Other significant artists included Nasaka Yūko, whose early work was inspired by iceblocks – along with Tanaka and Yamazaki, she was one of the few women associated with the movement – and Onoda Minoru, whose intricate dot paintings reference the delirious repetition of mass production.

When co-founder Yoshihara died in 1972, Gutai was disbanded. The main focus of his late work, inspired by Zen Buddhism, had been paintings of circles. Unsurprisingly, no two are alike.

Artworks by members of Gutai are currently on display as part of Performer and Participant: Gutai, Tate Modern, until November 2022. Curated by Catherine Wood, Senior Curator, International Art (Performance) and Helen O’Malley, Assistant Curator, Tate Modern.

Jennifer Higgie is Editor-at-Large of Frieze magazine. Her book on historic women’s self-portraits, The Mirror and the Palette, will be published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson in March.