Logan Kingsbeer, photographed by Cleo Valentine

© Cleo Valentine, courtesy Logan Kingsbeer

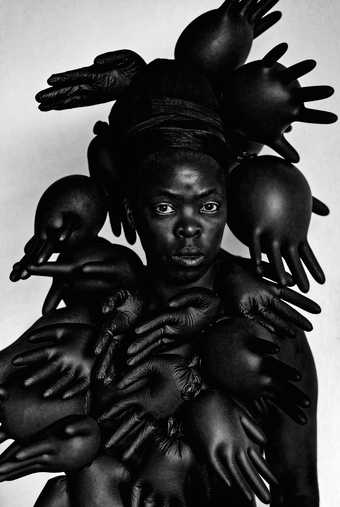

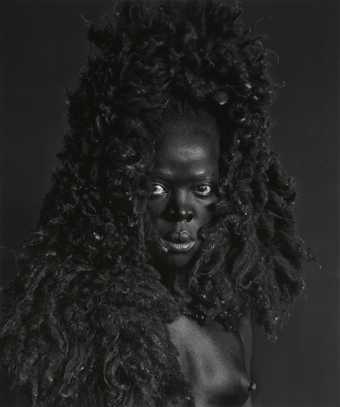

After I saw Zanele Muholi’s work for the first time, I couldn’t stop thinking about it. It was at their exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, and the first room showed a wall of powerful black-and-white photographic portraits taken by Muholi. Reading the wall text, I quickly realised that a number of these people had since been murdered for being lesbian, queer or transgender. At that moment, all I wanted to do was turn around and walk out before I burst into tears, but I knew that this exhibition was too important to turn my back on. I needed to experience this work, and acknowledge what Muholi was trying to capture.

On the opposite wall, a graph showed the increase in the number of murders and disappearances in this lesbian and transgender community between 2008 and 2017. As the list of names grew and grew, my heart sank even further.

Zanele Muholi

Siya Mcuta, Cape Town Station, Cape Town 2011

Gelatin silver print on paper

© Zanele Muholi, courtesy the artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

Looking back, it was an exhibition that changed my life. I couldn’t believe how brave Muholi – and these participants – were for carrying out such a dangerous project. They were taking a terrible risk to be part of a visual activist movement, since being identified as openly queer or transgender could cost them their lives. As a queer person who has very rarely had to fear for my safety on the grounds of my sexual or gender identity, the courage behind this work hit me to the core. This was my community, but here was a level of fear I had never experienced. I left the exhibition with a sense of mourning, but also a new awareness of the struggles of this community and of my own privilege as a white, queer person from New Zealand.

Three years have passed since I first saw Muholi’s exhibition in Amsterdam, and since then we’ve both come out as nonbinary; we’ve both changed our pronouns.

When I first heard Tate Modern was staging an exhibition of Muholi’s work, I jumped up and down with excitement. Visibility and representation are so important for underrepresented communities, and having an exhibition by a Black, queer, non-binary, South African artist and activist is the first step in welcoming into the galleries people who may not feel that Tate is for them.

Muholi’s exhibition has also prompted many discussions with colleagues at Tate around pronouns, gender identities and the importance of queer language. While it’s sometimes exhausting that these conversations fall on us LGBTQIA+ people to facilitate, they’ve mostly been positive, and I’ve met people who are eager to educate themselves about these issues.

I’m proud of how far we’ve come over the last few years, but I want everyone to feel empowered to do more. ‘Ally’ is a verb, and we need more people to put their solidarity into practice.

La Kingsbeer is Marketing Manager at Tate Britain, a chair of Tate’s LGBTQ+ Network and a freelance illustrator. Their pronouns are they/them/theirs.