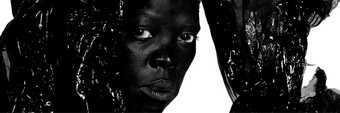

Chila Kumari Singh Burman working in her SPACE studio in Hackney, London, August 2020

Photo © Susanne Dietz

A dadaesque mannequin welcomes everybody to my studio, wearing a crown of anteater quills, assorted bling and blasts of fluorescent paint. This fabulous usher commands you to open your eyes and be fabulous, like me.

The studio is busy. A Hunter Penrose etching press ready for copper plates sits in a corner. Hundreds of glowing glass and glitter- glistening cones and screwballs from my Dad’s ice-cream van shimmer everywhere. Kitsch, plastic ice-cream spoons neatly ordered on white canvas are ready to dip in oil paint and be mashed up with my collection of found Punjabi treasures and peacock feathers from Hindu temples. These are all ready to show in an exhibition at the Stephen Lawrence Gallery in Greenwich next year, exploring the relationship between architectural sites and human trauma – hidden, buried, embedded in and embodied in the most unexpected places: like the romantic image of an ice-cream van, one that I had to scrub down as a child – sticky ripple and f lakes, sterilising Carpigiani Whippy machine bits... which was a nightmare because I had no time to do homework.

Spray paints and gold-leaf flakes line shelves, with boxes of diamante gems from Sri Lanka and London creating a Bollywood set-cum-science lab vibe. These resources wait in line for their turn to tell a story, to be part of the next experiment.

The wall opposite the door is mostly window, a huge opening letting in light. The blossoms on the trees below frame the housing estates that stretch towards the horizon. The view outwards balances the fullness and ordered chaos of my workspace.

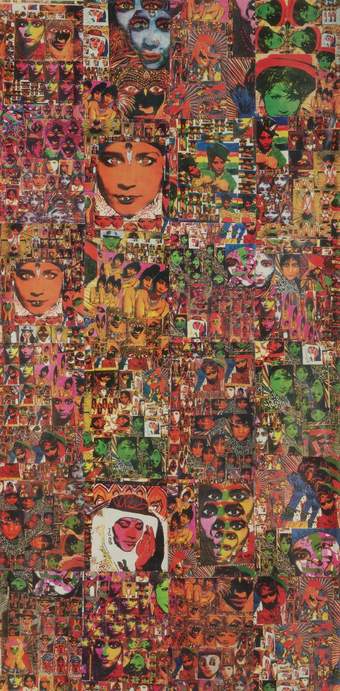

I’ve been working on several projects lately, including a collage commissioned by Great Ormond Street Hospital, and collating an inventory of my papers for Tate Archive. I’m also exploring developing some new work with Manchester Museum and their local South Asian/diaspora communities, for their new South Asia Gallery opening in 2022. I have a lot of shows in the pipeline; the next major one is the Tate Britain Winter Commission for the façade of the building. I’ve been collaging ideas on paper, computer, canvas and vinyl, and even embellished a 3D model of Tate Britain. This will open during the week of Diwali in November 2020. It’s a great opportunity for me to put Diwali on the Western art world’s landscape and an even bigger opportunity for showcasing my take on traditional and popular Indian culture.

Being true to who I am is of utmost importance. This means addressing my family and cultural heritage in my work, the big issues about social justice, identity, community, race, class and gender in today’s challenging world, just as I’ve done since my early-1980s Riot Series of etchings and lithographs, in Tate’s collection. I’ve always had my finger on the pulse. The political hot potato at the moment is the government’s neglect of culture up to now, and its low level of funding in response to the coronavirus.

View of Chila Kumari Singh Burman’s studio, including an embellished 3D model of Tate Britain made in preparation for her commission for the building’s façade

© Chila Kumari Singh Burman. All rights reserved, DACS 2020. Photo courtesy the artist

My artistic practice is expansive, covering over 30 years of working. I have a specialism in traditional printmaking and work in various media including photocopy art, painting, drawing, video, music, digital media, sculpture, installation, mural painting and photography. It’s wild, messy, surreal, abstract, zen, feminist, anarchic, figurative, textured, layered and all blinged-up with a razor-sharp political awareness. A clash between high art and popular culture. An eclectic mix of art and activism addressing global protest. Interrogating the family album, personal and collective memory. My approach to subjects is grounded in a tradition of graphic political satire generated from an adversarial position within the gender and identity politics of a postcolonial, class-orientated and media-saturated contemporary Britain.

The events of the last few months have raised the question of responsibility – to whom or to what? Art institutions need to know the history of racism in the UK especially in relation to art spaces and their own complicity in this. They need to learn, and learn from, the history of Black and Asian British art and artists, and how they have been treated by their own institutions. We need more people of colour in senior management and curatorial roles in art institutions. Decolonising UK art institutions also means having better relationships with local Black and Asian communities, as well as artists. Art institutions need to think critically about anti-racism and social justice – and commit to doing something about it.

I think the experience of the pandemic and the Black Lives Matter protests has forced many of us to stop and take stock of our physical and mental health, and to reflect on our practice. Hopefully this will lead to better-informed conversations and more effective strategies for tackling racism in the art world and beyond. My hope is for a ‘new normal’, where Asian people are seen as integral to British society, and I don’t have to keep explaining what UK Asian Culture is as an outsider. It’s more a hope than reality, maybe…

Tate Britain Winter Commission: Chila Kumari Singh Burman, Tate Britain, 14 November – 31 January 2021.