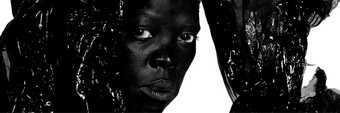

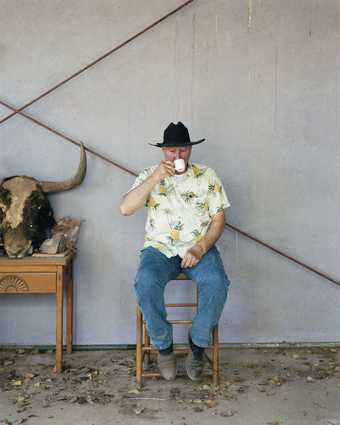

Bruce Nauman at his home in New Mexico, 2018, photographed by Alec Soth

© Alec Soth / Magnum Photos

Bruce Nauman (b.1941) was once asked to define the exact purpose of his wildly variegated (and, to those outside the inner precincts of the art world, incomprehensible) art. ‘To keep me busy’, he replied. This was a weirdly self-effacing thing to say: Nauman was in on the early waves of post-minimalist, conceptual, video, installation, and body art, and, in 2006, was ranked by Artfacts. net as the number one artist in the world – ahead of such household names among the avant-garde as Robert Rauschenberg and Gerhard Richter.

I’ve known Nauman for a long time, although I haven’t had much contact with him for a few years, save for the odd, sports-related email (back in the day, we were both big Los Angeles Lakers basketball fans). He’s friendly, absolutely unpretentious, and willing to talk about – or at least around – his art (in a kind of whispery voice that’s lower than my nasal, adolescent-sounding one.)

He was born in Fort Wayne, Indiana and, as a child, made model aeroplanes in his father’s basement workshop. Later on, he took to music, studying classical guitar and developing a taste for the composer Arnold Schoenberg’s 12-tone technique. (Schoenberg, the writer Samuel Beckett, and the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein all upset traditional Western notions of, respectively, music, literature, and philosophy, and they became Nauman’s background models for his rethinking of modern art.)

In 1966, Nauman was one of the first artists with a Master of Fine Arts degree to become really radical in his art. After graduate school, he lived in a few different places in California, then moved to New Mexico in 1979. He still lives there now – mostly because he’s a rancher who breeds and sells Quarter Horses (an American breed), but also because he prefers to make his art without the psychological middleman of a big-city art scene. (Note: Despite being regarded by the rest of the art world as having a gritty Gotham sensibility, Nauman has never lived in New York.)

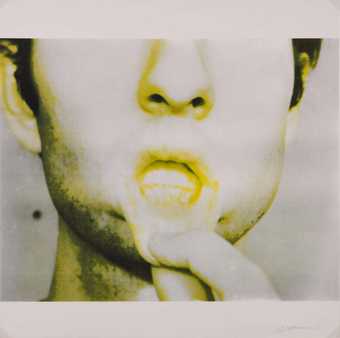

Bruce Nauman

b (1970)

Tate

To get an idea of the why and wherefore of Nauman’s work, a few things should be borne in mind. First, when he gets interested in something, his learning curve is, as Juliet Myers, his studio manager for years, says, ‘nearly vertical’. When he visited Venice in preparation for his role as the sole United States representative in the 2009 Biennale, he got hooked on espresso. So he researched everything that went into making it: the machines, the coffee beans and the grinders (he found that burrs, not blades, were the way to go); it’s safe to say that Nauman’s coffee is among the very best in New Mexico.

Second, he is, almost in spite of himself, a gifted draughtsman. His drawings – notes, plans, and ancillary clarifications more than objets-d’art in themselves – are strangely graceful and deft. Third, he’s very much a ‘word’ guy, which is to say that he’s one of the few artists to make text function well within his works of art, which are neither billboard lettering posing as mural, nor slim-volume grist for poetry that looks out of place in an art gallery. Finally, his signature style (that thing that all successful artists are supposed to have) is his lack of signature style.

In a 2001 interview, he discussed his ‘late work’ (most recent projects) with the curator Michael Auping: ‘I guess it’s late work. I hope it’s not too late. Maybe in the sense that there’s ten years of stuff around the studio and I’m using the leftovers, but I’ve always tended to do that anyway. Pieces that don’t work out generally get made into something else. This is just another instance of using what’s already there.’

One could argue for a definition of conceptual art as the open use of what’s already there. In 1953, Robert Rauschenberg obtained a drawing directly from fellow artist Willem de Kooning and, with his permission, erased it to make a work of art of his own. Eight years later, Rauschenberg fulfilled a portrait commission by telegramming: ‘This Is a Portrait of Iris Clert If I Say So.’ (Iris Clert was a gallery owner and curator.) In 1960, South American- born Dutch artist Stanley Brouwn declared that all the shoe stores in Amsterdam made up a show of his work; a year later, the Italian artist Piero Manzoni canned his own excrement (if you believe the labels on the tins) – the ultimate leftover. Forty years later, in a Turner Prize show, British artist Martin Creed exhibited (if that’s the word) a physically empty gallery in which the lights went on and off at given intervals.

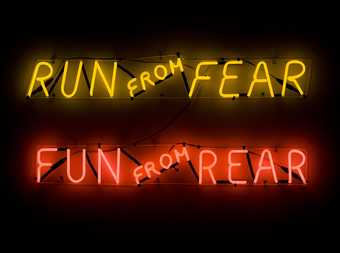

Bruce Nauman

Run From Fear 1972

Neon tubing with clear glass tubing suspension frames

© Bruce Nauman / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York and DACS, London 2020, courtesy MCA Chicago, photo: Nathan Keay

Of course, a theoretical case could be made that, at this late date in the history of modern and postmodern art, everything has been done; and any artist’s work, no matter how ostensibly ‘radical’ it purports to be, is merely riffing on something that’s been done at least once – and probably more times – before. When I taught art in a Californian university, not unlike the one where Nauman received his graduate degree (and only about a decade after he graduated), I had a clever student who printed up elegant calling cards with an embossed wedding-invitation font. The cards said: ‘It’s been done.’ He’d go to gallery exhibition openings and surreptitiously insert these into the frames of paintings, or onto the bases of sculptures.

Nauman knew from the get-go what that student knew. As a graduate student, he earned money by stretching and priming canvases for a painter on the faculty, and would watch the painter making his preliminary compositions in loosely brushed Prussian blue. He told a friend: ‘I don’t want to make art that way – where you know what you are going to do in advance.’ Looking back, years later, Nauman said: ‘When I was in art school, I thought art was something I would learn how to do, and then I would just do it. At a certain point I realised that it wasn’t going to work like that. Basically, I would have to start over every day and figure out what art was going to be.’

He pushed this idea in his early video and film works Bouncing in the Corner, No. 1 1968 and Bouncing Two Balls Between the Floor and Ceiling with Changing Rhythms 1967–8. Nauman said: ‘I was picking things that were hard to do, so that would be part of the tension of watching. I think I had the idea that you should put yourself in an awkward position and see what you can do with it. These kinds of pieces had to do with what happens if you take the artist’s tools away. Is he still an artist? What does he have to do to be an artist?’

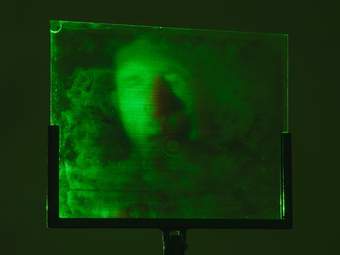

Bruce Nauman

Walking a Line 2019

3D projection

© Bruce Nauman / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York and DACS, London 2020, photo courtesy Sperone Westwater, New York

Although I’d heard of Nauman, and had seen a puzzling (to the local art world at the time) show that he had held in 1966 at the Nicholas Wilder Gallery on La Cienega Boulevard in west Los Angeles, I didn’t meet him until a couple of years after those bouncing-balls pieces. Our studios were in dilapidated buildings on the same side street in Pasadena. (Seaside Venice was the place where the more established L.A. artists plied their trades; smog-bound Pasadena was a distant second.) I was a painter, and he was one of those weird conceptual artists (the term ‘installation artist’ wasn’t yet common currency), so I didn’t quite trust him.

Eventually, I was invited up to his studio. To my painter’s eye, it was intolerably dark and cluttered. There were, however, some drawings lying around (Nauman was – and is – not precious about his preparatory work) and damn! if they weren’t good. Shortly thereafter, Nauman – whose idea of art materials encompasses almost everything, and who is not one to waste materials – asked me to be in a film he was shooting. I ran on a treadmill and was shot against a black background. My dutiful performance was, I heard later, left on the cutting-room floor; later, I saw an excerpt on a museum website, and there I was!

A final recollection in this mini-memoir is that Nauman and I both participated for several years in a Sunday artists’ basketball game in Santa Monica. Nauman was semi-frequently absent. When the question, ‘Where’s Bruce?’ was asked, the answer was inevitably: ‘Oh, he’s in Europe.’ He was, we realised, an international artist, more in the league of installation artist and sculptor Ed Kienholz than the more local heavies in Venice.

The critic (and de Kooning and Francis Bacon biographer) Mark Stevens succinctly describes Nauman’s approach as ‘slapstick sublime’. Those are the absurdist elements he’s referencing, as in Nauman’s ‘bouncing’ pieces. There is, however, a darker – well, at least laboratory-detached – side to Nauman’s art. He not only gives an audience something to look at, he does things to an audience, albeit by implication. His video installation Learned Helplessness in Rats (Rock and Roll Drummer) 1988 is not that far removed from putting us through a maze. Mapping the Studio I (Fat Chance John Cage) 2001, puts us in the queasy position of watching somebody (well, cats and rats) being observed, while wondering if somebody just might be mapping the museum by spying on us.

The art historian Jane Livingston says, ‘Bruce will find some little way to turn the knife: but it’s intellectual and perceptual, not psychological.’ To put it another way, an impossibly large version of that former student’s provocative calling card might read: ‘It might have been done before, but certainly not the way Bruce Nauman does it.’

Bruce Nauman, Tate Modern, 7 October – 21 February 2021. Curated by Andrea Lissoni, former Senior Curator, Film, Tate Modern, Nicholas Serota, former Director, Tate and Katy Wan, Assistant Curator, Tate Modern, and Leontine Coelewij, Curator Contemporary Art and Martijn van Nieuwenhuyzen, former Curator, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam. Supported by the Terra Foundation for American Art. With additional support from the Bruce Nauman Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate Americas Foundation, Tate International Council and Tate Patrons. Organised by Tate Modern and Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam in collaboration with Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan.

Peter Plagens is an artist, art critic and novelist based in New York.