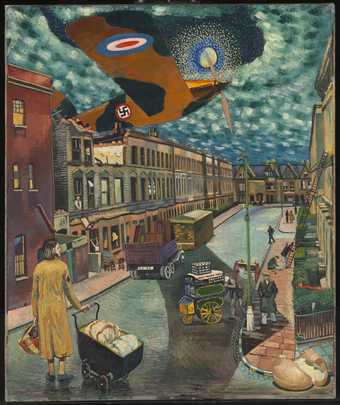

Director of the Tate Gallery John Rothenstein surveys the damage caused by a high-explosive bomb, 1940

Courtesy Tate Library and Archive (TGA 8726), photo: Tunbridge-Sedgwick

Eighty years ago this autumn, Tate Britain, then known as the Tate Gallery, was badly damaged by a high-explosive bomb dropped during the London Blitz. The then director, John Rothenstein, was sleeping in one of the galleries at the time and witnessed the bombing on 16 September 1940 firsthand:

‘Early one morning I was awoken by a terrific explosion to feel the massive building violently shaking and to hear an avalanche of masonry and glass... Since the raid was still in progress we could not use our torches, but by the inadequate light of the stars and bursting shells we crept through the wreckage from room to room, cautiously, because the firing of the A.A. guns brought down cascades of loosened roof glass. Outside the building on the east side, what half an hour before had been a road, pavement, lawn, and flowerbeds was now merged in one indistinguishable desolation.’

Three months later, on 19 December 1940, after he and his wife Elizabeth had moved to a safer area to sleep – ‘under an archway outside the ladies’ lavatory’ – two incendiary bombs penetrated the building’s roof and set fire to the f loorboards in one of the galleries, the damage compounded by inches of rain. With the gallery in a near-derelict state, its roof missing and few doors or windows, it became impossible to work in the building, so operations were moved to Eastington Hall in Worcestershire, and later to Sudeley Castle in Gloucestershire.