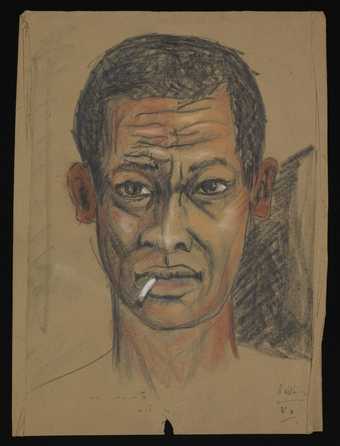

Aubrey Williams

Painting of the head and shoulders of a man ([c.1979])

Tate Archive

To be honest, I take my skin for granted. I always have. I’ve tried to hide the neglect with attempts at self-care, smothering my skin in cocoa butter, but it’s never enough to heal the cracks in my identity. While I’m proud to be Black, I’ve never really understood what that meant.

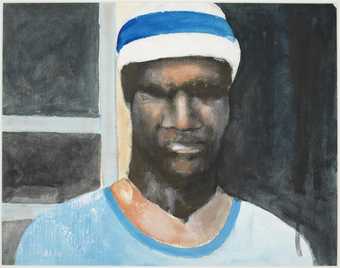

When I first saw the man in blue in Aubrey Williams’s picture in Tate’s archive, I thought he seemed strangely complete, despite the fact that he is missing his eyes. A rudimentary understanding of Williams’s eyeless man might be that representation is important and Black folk don’t see themselves reflected in the world. But there’s more to the metaphor. They say eyes are the window to the soul, and so, without his vision, this man can neither see nor be seen. This reading wasn’t lost on me; a fellow man who rarely sees himself reflected.

The transformative power of representation is dead to those that society overlooks, or misrepresents, Williams’s work now screams. It’s not enough to occupy white spaces; rather, equality comes about by allowing Blackness the same privileges as whiteness. Take the gallery setting as an example, where Black artists are frequently displayed out of context, and their experiences cannot then be understood. To truly be seen, Black artists must be allowed to write their own narratives.

What is significant about this moment is that, for the first time, white people and people of colour are coming together and exploring what Blackness means. White folk are realising that they need to learn more. More people are pushing for the same thing, and our struggle is beginning to feel less hopeless.

These issues won’t be changed through existing political systems; it’s clear, much to the dismay of those who have been pushing for change, that our political framework is still not fit for purpose when tackling issues about race. Rather, as we have seen in the past few months, it’s by using our collective voices and operating outside these systems, that things that have begun to change.

Art can help us understand things that are difficult to grasp. In the same way that Williams portrayed a particular sense of Blackness 40 years ago, we must cast a light on our own meanings of Blackness and what it signifies now. Can we illuminate Blackness in a new and equal way? If so, the time to do so is now; perhaps the man’s eyes were there all along – they just hadn’t been allowed the chance to open.

To explore Tate’s digitised archive collections visit tate.org.uk/art/archive/collections.

Rudi Minto de Wijs is Marketing Officer at Tate and Co-Chair of Tate’s BAME Network.