Edie Fake

The Bindery 2018

Gouache and ink on panel

© Edie Fake, courtesy Western Exhibitions, Chicago

Recent years have seen trans, non-binary and gender non-conforming artists attain unprecedented visibility, examples of their work appearing at a growing list of major venues, in both group and solo exhibitions. Does this signal an enlightened art world learning to embrace gender diversity with ease? Or do those sunny uplands now afford a clearer view of slopes we’ve yet to climb? Before we salute the arts as society’s progressive compass – a selfimage the sector cherishes fondly – let us observe how recently the prospect of transperson- as-artist could arouse derision within these pages. In Samuel Nyholm’s cartoon of a gallery private view, printed alongside Tate Etc.’s spring 2010 editorial, a bemused art critic, wine glass in hand, is introduced to ‘Replicator Human Elixir, an upcoming trans-sexual artist’. Replicator – an invented character in every sense – has come dressed only in nipple stickers, a thong and a telephonist’s headset.

Near the very spot, ten years on, this real-life trans-sexual has her say. There’s progress for you. Elixir may already dwell in the forlorn archives of Now We Know Better, yet her caricatured image remains instructive. Readers were invited to snort over the artist’s name and curious outfit, symptoms of the delusional identities and sexual kinks ascribed wearyingly often to trans women. The visual punch line is Elixir’s physique. Statuesque, hairy, and what used to be termed ‘pre-op’, she embodies the virile trans bogeywoman who excites so much contemporary disquiet over trans equality. Women with such bodies have endured calls for their exclusion from numerous occupations: nursing, feminist activism, sports, teaching children, visiting the loo… The prospect of trans people making art has not triggered the same alarms over public safety. Even so, the path of a gender diverse artist is hardly free from systemic challenges.

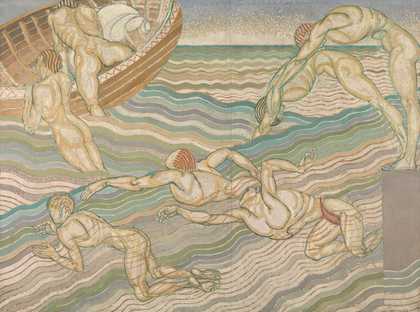

Western visual art can be inhospitable territory for trans bodies. The figurative tradition not merely absorbed but helped formalise the West’s binary model of gendered embodiment. Artistic archetypes of the human form shift, but a sharp divide between female and male has been a constant – a cosmic dichotomy inscribed only more reductively in 20th-century modernism. In art, as in life, ambiguity of sex has drawn censure. And the artists mocked for such lapses of gender legibility have tended to be too queer, too female, or both. Michelangelo’s powerful, muscular women – the target of many a homophobic sneer – might almost be ancestors to Elixir’s brawny, comedy body.

If trans bodies can chafe against ingrained norms of artistic competence, transition disorders the professional biography that underpins reputations within the arts. The preferred career arc is one of single-minded ascent: art schools, gallery shows (ever bigger and better), awards and commissions. Names are not expected to alter along the way, never mind pronouns or genitals. As artists who switch surnames at marriage often learn, the art world struggles to digest discontinuities. Slippery trans life narratives are harder still to assimilate. Museums – fearful of ‘getting it wrong’, though ill-prepared for the challenge – are even now wrestling with internal hesitations over names, pronouns and cataloguing choices.

At least we may say their will to do so grows. With many arts institutions striving to be more inclusive, interest in trans life experience is beginning to dispel earlier aversions. Belated acknowledgement is not always without biases. In the new quest for authenticity, works of art are saddled with holding space for whole communities. Vivid glimpses of gender-diverse bodies, alongside other spectacles of queer transgression, are accordingly prized. This, I suspect, drives the disproportionate popularity of film, photography and performance in this corner of modern curating. More than one upcoming trans artist has lamented how isolated moments of self-exposure overshadow other areas of their work. (As an experiment, picture a world where cisgender, male artists need to strip off to get discovered.) The licence to deal with ‘universal’ concerns is a privilege rarely extended to artists seen as speaking for a marginalised identity.

Perhaps unwittingly, Elixir’s near nakedness hits upon the stubborn predicament of the trans artist. If her fascinating body at times helps her through the gallery door, that same allure threatens to overshadow her work – the real showpiece too often her own otherness. In the eyes of cisgender gallerists and audiences she remains the trans-sexual artist: a thrilling visitor rather than a core addition to collections; perpetually the upcoming novelty, while her cisgender peers sail on towards mid-career retrospectives.

Alex Pilcher is Senior Web Developer at Tate and the author of A Queer Little History of Art (2017) and Love (2019), both published by Tate Publishing.