There are three prerequisites for seeing Sarah Lucas’s work. One is to leave aside the now-tired question: “Is it art?” The second is to stop lumping together her output with that of near contemporaries Tracey Emin and Damien Hirst. The third is to leave squeamishness of all kinds at the door. This is especially necessary if you like fried eggs, chicken and pork, because you are quite likely to go off them permanently while viewing her art.

Sarah Lucas

Bunny Gets Snookered #2 [Unwrapped] 1997

Photo: Samuel Leuenberger

Collection Goetz

The third prerequisite applies also to reading this essay, because Lucas’s theme is sex, addressed in a manner that is frank to the point of obscenity – unpretty, abrupt, raw, sometimes gruesomely funny and sometimes unsentimentally poignant – and therefore use of her own vocabulary, explicit or implied, is inescapable. She does not represent breasts and vaginas, but tits and cunts; not penises and male masturbation, but cocks and wanking. Her subject is an uncooked perspective on the nature of sex, and particularly the place of women as orifices, receptacles, as meat or fowl prepared not for the table but the bed, as something for consumption or deposit – exclusively, the deposit of male excretions.

This makes her sound like an angry feminist, wounded and disturbed; but that’s not her message. The view she is examining is not so much an adult male sexist objectification of women, as a nervous male adolescent smuttiness. She makes us see a portrait of female sexuality drawn by the ignorance and desire of testosterone-plagued teenage boys, protecting themselves against the alarming, fascinating, disgusting, hungered-for female sex by attacking and denigrating it, calling it dirty names, affecting to perceive it only as an arrangement of the aforementioned tits and cunts.

Sarah Lucas

Au Naturel [wrapped] 1994

Photo: Samuel Leuenberger © Private collection

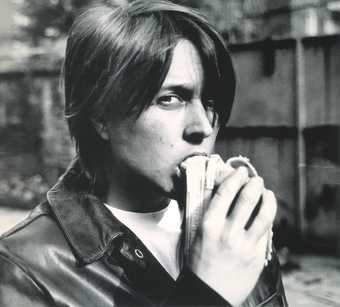

Lucas’s accurate knowledge of this viewpoint is unsurprising given her remark, in an interview, that “I was quite a tomboy when I was growing up. I liked hanging out with a lot of boys, and I sort of got used to their way of talking about sex”. But of course her exploration of their viewpoint, and her adoption of its poses – her jeans and boots, short hair, leather jackets, her splayed-knees way of sitting, the androgynous style of her self-portraits – is not an endorsement of the teenage male perspective, for in that quotation she continues: “And at the same time as thinking it was funny, I suppose I was a bit aware that it also applied to me, and I’ve always had those two attitudes. I did enjoy it – but at the same time I must have shuddered inwardly, I think.”

Yet Lucas does not follow any of the natural possibilities that might flow from her experience of the dirty-talking swagger and group bravado of inexperienced boys. She does not give feminist sermons or claim victimhood and sympathy. Instead she produces an ironic, unvarnished, bald statement, which challenges the shallowness of the view and outfaces it, turning it absolutely against itself, and makes something witty and perceptive.

Sarah Lucas

Bondage Up Yours 2000

Photo: Samuel Leuenberger

To get the measure of her work it’s perhaps worth thinking what people who dislike it might say. They might say that it seems obvious and unsubtle, that it consists in an obsession with unhappy sex, toilets, especially dirty ones, and cigarettes. They might say that it is reductive in its attitude to the female body, with two fried eggs or melons representing breasts, and fish – rotting, or vacuum-packed – the vulva. Sexual woman is a pair of pork hind-legs held together by dirty knickers on a stained mattress, or a plucked chicken on the wire frame of a bed, its legs tied apart to splay open its orifice.

These critics might speculate why the sex in Lucas’s work is always and only prospective or retrospective for females, but onanistically occurrent for males. The chicken and the pork legs lie in gaping preparedness for penetration, the bunny figures (stuffed tights tied to chairs) sprawl in post-coital postures, whereas male sexual activity is represented as masturbation actually happening. There is a “wanking armchair”, there is a room with a motor-driven hand going solemnly up and down, there are two wanking hands mounted at right-angles to the wall (memorials of past boyfriends, the labels tell us), there is another motor-driven wanking hand in a glass case. So many wanking hands and arms bespeak obsession, well enough – until one sees that she is either honouring or embarrassing past boyfriends, and giving them the due of precise observation: one of the cupped hands has the little finger slightly raised, as when a refined lady drinks tea.

Sarah Lucas making final adjustments

Photo: Samuel Leuenberger

Detractors doubtless think that the only aim of the pieces is to shock and nauseate, and that they also betray a profound self-disgust on Lucas’s part, a contempt for male sexuality. From this hostile perspective the key word for both the work and the attitude it expresses (remembering Hazlitt’s term of art,”gusto”) can only be “grotty”. The photographs give the judgment support: they show the provenance of what the critic would allege is her seedy outlook: a scummy kitchen, filthy toilet bowls telling us that everything goes down the pan and that woman is a pan made of meat and fish designed for the receipt of male evacuations.

Well, no doubt some of this is true. Not all of the work is an invariable pleasure to behold, though some of it is. But pleasure is not the point. She offers commentary, and although no commentary can fail to imply a value judgment of some kind, there is something curiously neutral about Lucas’s view. Even so, to suggest that there is little more to her art than a desire to be rude and irreverent, and to rub our noses in squalid and unappealing truths, is to miss the point. To get that point one has to take more account of the pieces that say more than “grotty sex”.

The cigarette pieces and the photographs soften the edge of the more sexually orientated sculptures. Putting the former alongside the latter draws attention to the fact that some of them are studies in uncovering what society covers up: the parts that curiosity and prurience fetishise because they are made inaccessible. Using ordinary objects – chairs, buckets, tables – as staging, and foodstuffs to represent male and female sex organs, she appears to want us not just to look at the specifically sexual in human anatomy, but to notice it properly, and to see the exploitative and absurd sides of it.

The most poignant of the pieces is Chuffing Away to Oblivion 1996, a packing-case room wallpapered with tabloid stories about sex, boobs and perverts. The headlines scream: “Get Your Ditties Out For the Boys”, “Open Wide!”, “You Can’t Lick Getting Your Oats”, “Clap Victim Chokes Lover”, “It Was Neckie Not Nookie”, “George Is A Big Nob Now”, “Is A Big Bust Best?” Their crassness adds a further dimension to Lucas’s commentary on the adolescent nature of laddish caricatures of female sexuality. Her point, or at least a major part of it, seems to be that much of the sexual aspect of life consists of attitudes and anxieties formed in exactly such caricatures, and that even women more than half buy into them. In fact, her sculptures make one ask whether women invite, expect or even enjoy the reductive view of themselves - and at the same time whether they are covertly laughing at boys as wankers, and at the boys’ fear of the female that makes them mouth and enact such denigrations of it.

The essential Lucas portrayal of the male is Get off your Horse and Drink your Milk 1994, a naked young man holding a milk bottle to his crotch as a penis, with two biscuits for testicles. The milk bottle is an appropriate choice: a stiff tubular shape with white stuff in it. The essential Lucas female, Spinster 2000, is the arrangement of those two fried eggs for breasts and fish for a vulva. Sex is a mattress with a fluorescent tube light pierced through it. For those critics envisaged earlier, all his (together with dirty toilets) offers only an unpleasantly ironised view of the flushable nature of sex as a weary yet restless desire for friction, all constituting no more than a somewhat grown-up version of what makes six year olds giggle. Some of the critical reaction in Switzerland reflected just such a view: “trash-feminism”, “agressif et vulgaire”, “Alles ist Sex” featured among the comments.

Sarah Lucas

Installation view of entrance hall

Photo: Samuel Leuenberger

But then you notice the pair of boots with razor-blades embedded in the toes near an array of objects chosen for their phallic shape (corn on the cob, gourd, marrow), and that near the wheelbarrow-pushing dwarf sculpted out of cigarettes there is a copy of the Sunday Sport reporting the claim by a female midget who works as a topless kiss-o-gram that lots of men fancy her. These weirdly imaginative and unexpected juxtapositions refute any suggestion that Lucas has a single obsession in mind. There is something more complicated going on. Some might say that the chief point of her art is that it is a joke, a vehicle for her dark, distinctive humour, and that if one sees it as trying to persuade us to think differently about the place of sex and sexuality in life, that is just a lucky accident. But Lucas’s work definitely spills over boundaries – not only of convention, and of the clumsy categorisations of contemporary art, but also of notions of taste too.