Kenneth Clark begins his classic treatise The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form by making a distinction between the naked and the nude: “The English language, with its elaborate generosity, distinguishes between the naked and the nude. To be naked is to be deprived of our clothes, and the word implies some of the embarrassment most of us feel in that condition. The word ‘nude’, on the other hand, carries, in educated usage, no uncomfortable overtone. The vague image it projects into the mind is not of a huddled and defenseless body, but of a balanced, prosperous and confident body: the body re-formed.” It has often been asserted that Modernism begins with Manet, in particular with those paintings wherein the vexations of the unclothed female body burst forth with a power of disquietude that appalled the public: Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe 1863 and Olympia 1863. The former picture had been exhibited at the Salon des Refusés, “to that extent, officially beyond the pale of art”, as another Clark – T.J. Clark – remarks in his essay Olympia’s Choice, whereas Olympia was the shocker of the official Salon of 1865. Both paintings display an uncertainty about the status of the nude female figure, an uncertainty that points perhaps towards Kenneth Clark’s distinction between the naked and the nude. These women fail to sustain the idealisation of the nude, slipping decisively into the embarrassing (for some) terrain of the naked. In other words, Manet deprives his models of the acceptable academic veneer of classical nudity, forcing them into the modern age, a naked age, disturbingly and yet ambiguously contemporary.

T.J. Clark continues his analysis by examining the silence of the contemporary Parisian critics concerning the obvious source of Olympia (Titian’s great nude, The Venus of Urbino, 1538), compared with their open acknowledgement of the source for Le Dèjeuner sur l’herbe (a work of Titian that was commonly attributed to Giorgione in the nineteenth century and known as the Fête champêtre, c.1510–11): “Critics certainly came to laugh at its mistakes and incoherences, and yet the best way to do so was to point out what Manet’s picture derived from - and how incompetently… But in 1865 none of this took place. If the revisions of the Venus could be seen at all, they could not be said.” He goes on to say:”The past was travestied in Olympia: it was subject to a kind of degenerate simian imitation, in which the nude was stripped of its last feminine qualities, its fleshiness, its very humanity, and left as ‘une forme quelconque’ – a rubber-covered gorilla flexing its hand above its crotch.”

The complexity of Clark’s analysis of the reception of Olympia does not bear treatment in a short essay. Suffice to note that a crisis in the depiction of the nude was already, in his view, well underway in the academic nudes of the Salons - the vacuous, silly, trashy Venuses and nymphs of Cabanel, Bouguereau and Gèrôme, to cite only three relatively more distinguished examples – and that the scandal of Olympia was indeed her modernity, a prostitute plainly and unapologetically, rather than a fille de la rue gussied up as Phrynè or Danaë.

Kenneth Clark’s remarks on Olympia are much more modest, but still adumbrate the radical break that Manet’s painting constitutes:”The Olympia is a portrait of an individual, whose interesting but sharply characteristic body is placed exactly where one would expect to find it. Amateurs were thus suddenly reminded of the circumstances under which actual nudity was familiar to them, and their embarrassment is understandable.” Those amateurs would be understandably embarrassed to see nakedness in such familiar circumstances: in a brothel, where they are paying clients.

If the naked and the nude as archetypes stand at the outset of Modernism, then both became thoroughly discredited and disposed of by Modernism’s end. And yet the unclothed figure persisted in certain forms. Félix Vallotton had been a member of the avant-garde Nabis group in the last decade of the nineteenth century, and in such paintings as Femme nue assise dans un fauteuil 1897 and Femmes nues aux chat c.1898 he subjected the nude to the flattening and the unnaturalistic colourations that were also typical of his compeers Bonnard, Denis Sèrusier and Vuillard. But by the first decade of the twentieth century, his nudes begin to change. From the vantage of Modernist criticism and art history, they degenerate, becoming, on the whole, more academic. Yet with hindsight we can discern in Vallotton’s later nudes – and there are many of them – characteristics that render them very contemporary. Nu assis 1910 is stunningly prescient with respect to John Currin’s nudes of the 1990s. This woman looks very much like a stout bourgeoise, and her no-nonsense hairdo attests to her conventional background: no glowing, flowing tresses here, no savage, Baudelairean chevelure . Her face is ordinary, her expression smiling and bland; at best she’s jolie laide. But Vallotton does play oddly with the colouration of her flesh, a hint perhaps of his Nabis past. The flesh tones of the body are those of the morgue, grey and purple; the face, however, looks flushed, reddened, desirous, horny. The Nu assis is a sexed-up corpse, a banal succubus. Were the trappings of the exotic or supernatural more in evidence – as they are, for instance, in the nudes of Gustave Moreau or Fernand Khnopff – Vallotton’s odalisque would appear more acceptable and less disconcerting, because she would belong to a readily identifiable fin-de-siècle feminine typology.

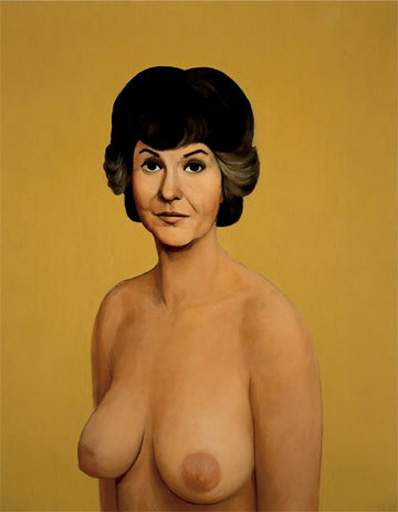

John Curin

Bea Arthur Naked 1991

Private collection, courtesy Gagosian Gallery

Vallotton’s Nu assis wreaks havoc on the idealised nude, but she doesn’t quite adhere to Clark’s description of the naked. Instead, wavering between academicism and almost gross realism, she comes off as a sly parody. She appears comfortable and confident in the amplitude of her dead flesh.The Nu allongè au tapis rouge 1909 likewise plays fast and loose with the conventions of the nude. Writing of Boucher, Kenneth Clark notes: “The Venus of the dix-huitième extends the range of the nude in one memorable way: far more frequently than any of her sisters, she shows us her back. Looked at simply as form, as relationship of plane and protuberance, it might be argued that the back view of the female body is more satisfactory than the front. That the beauty of this aspect was appreciated in antiquity we know from such a figure as the Venus of Syracuse. But the Hermaphrodite and the Callipygian Venus suggest that it was also symbolic of lust.” In the Nu allongè, Vallotton explicitly alludes to the hermaphroditic figure and the many nudes that borrow its pose; for example,Velásquez’s Rokeby Venus and Boucher’s Miss O’Murphy.”Freshness of desire has seldom been more delicately expressed than by Miss O’Murphy’s round young limbs,” comments Clark with the barest hint of prurience, “as they sprawl with undisguised satisfaction on the cushions of her sofa.” Vallotton’s nude is less fresh, more prurient. As with the Nu assis of the following year, his Nu allongè displays a visual incoherence in the handling of the flesh tones. In this instance, the torso and swelling buttocks are of a mostly chalky white hue, while the face and the hands are curiously flushed. The face and hairstyle again do not suggest the comfortable distance of antique references, but are very much of a contemporary moment.

This is the Venus of a weekday afternoon tryst, a Céleste or Marie of the Parisian banlieues, having just refreshed her maquillage and awaiting her paramour. The face itself is weird, deliquescent; one eye looks like it’s about to slip with slatternly languor from its very socket. Her feet are very heavily shadowed, but the effect is simply that they are dirty.

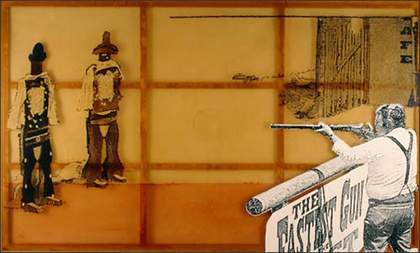

Vallotton’s loyalty to the nude as subject remains constant until his death in 1925. It comes as no surprise that these paintings have been largely ignored, compared with the works of his Nabis period. Sometimes they are just bad, as with the Vènus marine 1913, a clumsy, ludicrous blond on the half shell, her expression wavering between vacancy and, perhaps, bitchiness. She’s a spoiled mondaine who travesties the goddess she purportedly embodies. But paintings such as this presage the later works of the Modernist agent provocateur Francis Picabia. Indeed, while Vallotton’s later nudes have remained obscure, recently it seems that Picabia’s “bad” figurative paintings of the 1930s and 1940s have achieved a prominence virtually eclipsing his acceptable Dadaist travesties of the teens and 1920s.’Dear Painter, paint me…’, an exhibition mounted at the Centre Pompidou in 2002, bore the subtitle ‘Painting the Figure since late Picabia’. Alison Gingeras, one of the curators, wrote:”Beginning with Francis Picabia’s late nudes from the early 1940s, the question of painting as a filter of mass media’s impact on both individual and collective sense of identity has emerged as a key preoccupation of the artists in the exhibition.” Among them were Sigmar Polke, Martin Kippenberger, Neo Rauch, John Currin, Luc Tuymans and Elizabeth Peyton.”These notorious paintings - shunned for their ‘regression’ into realism and their embrace of kitsch - drew their pictorial source from tawdry black and white photographs culled from soft-core pornography magazines.”Picabia’s Portrait de Suzy Solidor (1933) is an early example of this kitsch revanchism. Anatomically bizarre, his Suzy Solidor, with her heavy blue mascara and smiling, parted red lips, also suspires an unmistakable prurience; the crude, dirty shadows outlining her legs and arms betoken a dirtiness of another sort. Suzy Solidor may yet be recuperated as a Dadaist travesty. The somewhat more competent albeit trashy technique of Femmes au Bulldog, Deux amies and La brune et la blonde (all 1941–2) if anything renders these pictures more scandalous: rude, crude and dangerous to know. Picabia’s lewd nudes may lend a certain contrarian Modernist lineage to the work of John Currin, but one wonders if Currin, so conversant in the art of the Old Masters, is at all familiar with Félix Vallotton? I’ve already mentioned the Nu assis as an extraordinary precursor for Currin’s own “bad” nudes, and I could easily add Le Printemps 1908, an especially ugly and stupid-looking evocation of Primavera. But the most astonishing comparison is between Vallotton’s Etude de fesses c.1884 and Currin’s Bottom 1991. The corporeality of the Vallotton buttocks is almost repulsive as he expends all his resources of painterly technique on the depiction of stretch marks and cellulite. Currin’s painting, on the other hand, seems relatively restrained, evincing an almost Cycladic elegance and symmetry. Scarcely the sort of conclusion one would expect? Even in the case of one of Currin’s most deservedly famous, or notorious, early paintings, Bea Arthur Naked 1991, the sitcom star preserves a certain restraint, dignity even, that militates against the overtly camp/kitsch (or possibly anti-feminist) readings of the picture that so readily come to mind. Perhaps the Arthur portrait is going rather against the grain of the Currin mode, even as it was only coalescing in the early 1990s – the exception that, maybe, proves the rule of perversion. This cannot be said for Vallotton’s nudes – distorted, freakish, moribund and whorish in multifarious variations.