In the mid-1920s, Austrian novelist and reporter Joseph Roth wrote a series of articles on the metropolitan frenzy of Berlin, a city which, as its citizens and visitors have seemingly never ceased noting, appears always on the edge of reinvention. According to Roth, the city is a giddy blur of movement, much of it circular, mechanical, repetitive. And yet these circuits are always new, ever about to spin out of control: he is thrilled by the noisy tangle of a railway junction, a roller-coaster ride in Luna Park, a department store’s escalator (“it doesn’t even climb, it flies”), the hot centrifuge of a six-day indoor cycle race. All of this circular speed has the odd effect of making time slow down: “Everything is spinning, only time stands still. The rotation goes on forever.” At the same time, another observer, the exiled Vladimir Nabokov, was watching the Berlin traffic with an equally visionary eye, but coming to a less enchanted conclusion. In the twenty-first century, he conjectured, “some oddball of a writer” would look at a tram from the Berlin of the 1920s and see only a kitsch remnant, an obsolete exhibit fit for “the Museum of Past Technology”.

Tacita Dean is not quite that oddball writer, nor does her work exactly curate the defunct machinery of the past in the manner imagined by Nabokov. It is instead something like a deft amalgam of the vantage points of Nabokov and Roth: a cultivated perspective that is both spiralling towards the future and unravelling into the past. In the essay that accompanies her film Fernsehturm 2001, Dean writes, with Stanley Kubrick in mind: “The revolving sphere in space still remains our last image of the future, and yet it is still firmly locked in the past.” The film itself is a sort of terrestrial 2001 . Atop Berlin’s iconic television tower, a restaurant suavely revolves: a space Dean first visited on an art college excursion in 1986. At that time, it took an hour for the surrounding city to orbit the tower. It has since speeded up, but although it now takes only 30 minutes for the view to complete a single revolution, everything else seems to have stood still. The visitors are mostly elderly, and have probably been coming here for years; West Berliners show little interest in this revolving allegory of the East. Before Dean’s static but mobile camera, the tower looks to be adrift, airlocked and serene, above a history which is visibly being rebuilt by the cranes below. At the end of Fernsehturm, the dimly lit restaurant is suddenly aflare with light as the staff prepare to close, and Berlin has vanished, as if, all along, this televisual ghost had dreamt it into being.

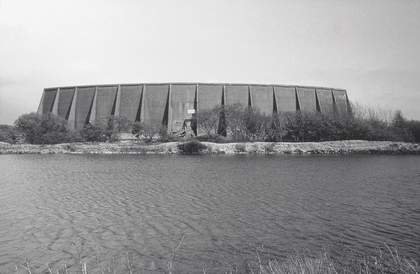

Dean’s art has long been exercised by this sort of spatial and temporal confusion. She is intrigued by eccentric images of the future that have been abandoned, left to leach their enigmatic energies into the surrounding territory. Such structures seem to bypass the present, setting up instead a strange relay between past and future, between utopia and nostalgia. Which is not to say that they partake merely of that generalised retro-futurist sensibility that has been everywhere, for example, in the cinematic futures of the past twenty years or so. Dean’s anachrony is altogether more precise and more mysterious than that: it appears, specifically, in the relationship between the hectic and fuddled history of the object itself and the long, calm meditation of the artist’s camera. It’s not, in other words, a matter of iconography, but of lingering presence, of a time that allows the historical shadows to gather.

In Sound Mirrors 1999, for instance, the vast concrete listening devices erected by the British military in the 1930s to detect German aircraft approaching the coast of Kent are not only images of an abandoned future (the kind of cheap frisson you get looking at a resurrected airship, say), but evidence of a protracted and uneasy accommodation of artefact and landscape. These ghosts are tragic, palpable, doleful presences. (Until recently, the largest of the mirrors bore this graffito: “I hate myself and I want to die.”) In Bubble House (1999), Dean had already discovered - on the Caribbean island of Cayman Brac, while searching for the abandoned boat of Donald Crowhurst, whose story formed the basis of her Disappearance at Sea (1996) and Teignmouth Electron (2000) - another misplaced and decayed relic of a time never to come: an unfinished, futuristic dwelling abandoned by an imprisoned fraudster. And in Boots (2003), she essayed a more complex reflection on architecture and memory, as an old man reminisces about (actually, invents) the past of an art deco villa in Portugal.

Tacita Dean

Sound Mirrors 1999

Film still

© Courtesy the artist, Frith Street Gallery, London and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York and Paris

But time and again it is Berlin, Dean’s adopted city, that has allowed her to give a special sort of historical resonance to her experiments in architectural time travel. (The Berlin films are also, as it happens, among her most beautiful: irradiated by sunsets so extravagant it seems the city, or the film itself, is on fire.) In the most recent, Palast 2004, she turns her attention to one of the city’s most controversial buildings. Among the last edicts of the old GDR in 1990 was an order to close the vast Palace of the Republic on Schlossplatz (then Marx Engelsplatz) when it was found to be riddled with asbestos. The building has stood empty ever since, and will soon be demolished. Opened in 1976, it was in part designed to demonstrate the ostensible modernising of the GDR, to foster a new cultural affinity between East and West. But in the era of actual unity it has come instead to symbolise a past many would like to accelerate away from as swiftly as possible.

Dean’s Palast is an effort to frame this doomed edifice, briefly, in the rear-view mirror of history. As always, however, the chronology turns out to be more convoluted. On the soundtrack, a modernity that Nabokov and Roth would have recognised can be heard: the traffic circles noisily out of shot, and occasional voices rise above it for a moment. But the building, clad in a pale brown glass that turns everything to gold, reflects mostly, at first, empty sky. Or rather, a sky roiling with ravishing, golden cloudscapes: the Modernist grid of the building’s façade encloses a slowly swirling turbulence that is practically Romantic in its hazy allure. Each expanse of glass is a screen on which is projected a separate scene from the city’s transformation. Gradually, other buildings and objects are reflected, but only ever obscurely: gleaming curves and spikes that might be glimpses of the nearby TV tower turn out to be streetlights, then the spire of a church, and finally, recognisably, the Fernsehturm itself. Equestrian statuary, rearing up in silhouette, is suddenly weak and hobbled beside the bold figures of contemporary graffiti. The city that the palace reflects might be already ruined, so dismembered does it look here, caught between the twin screens of the condemned building and Dean’s film (itself shot on the ruined, anachronistic medium of 16mm film). It is impossible to see these fragments of the city without recalling photographs of a bombed and shelled Berlin half a century ago.

Palast, however, is also a timely intervention in another era of the rebuilding of Berlin. The Palace of the Republic was constructed on the site of the Baroque Royal Palace, which had been damaged by bombing and finally demolished (as a supposed symbol of German militarism) in 1950. The now imaginary Schloss has been the object of a complex sort of nostalgia: itself the image of a future curtailed by the Communist regime, it may now be rebuilt as a monument to a future Berlin. In such a circumstance, both the supporters of the reborn Schloss and of the fading palace (there are predictably fewer of these) seem to oscillate between the roles of reactionary and renovator. Dean’s film sets this perplex of historical emotions into spectral movement, revealing the fabric of the city as a screen on which are projected wholly enigmatic impulses, unknown even to the citizens themselves.

Tacita Dean

Pie 2003

Film still

© Courtesy the artist, Frith Street Gallery, London and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York and Paris

In her book The Future of Nostalgia, Svetlana Boym writes:”Berlin is a city of monuments and unintentional memorialisations. In contrast to major monumental sites connected to German history, the involuntary memorialisations are material embodiments of this transitional present and are themselves transitory. With time they will only be preserved in stories and souvenir photographs.” The memories of the city are as fragile and as persistent as the bereft photographs Dean collected from the flea markets of Berlin for Floh 2001, or the mysterious opera programmes (with inexplicable holes cut in their covers), acquired in the same way, which are the subjects of her recent work. They are as fleeting as the magpies that she watches from the window of her Berlin studio in Pie 2003, and as certain to return. As Nabokov put it: “The future is but the obsolete in reverse.”