The films of Morgan Fisher have existed under the radar for more than twenty years. This is partly because he works in that filmic Bermuda Triangle between the avant-garde, the commercial movie industry and contemporary art. Being based in Los Angeles – where the only kind of cinematic culture is the blockbuster – can’t have helped. Away from New York, around whose creative inhabitants the foundations of serious film writing were built, Fisher avoided being anointed as one of the prime “Structural” filmmakers (who included Michael Snow, Paul Sharits and Hollis Frampton). However, this gave him a freedom to be as idiosyncratic as he wished.

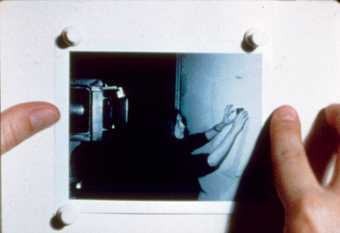

The majority of Fisher’s works are directly concerned with the machinery of cinema. He creates systems and rules that exploit the apparatus, physical material and production methods of the movies. Picture and Sound Rushes (1973) takes the form of a lecture in which his deadpan discourse describes the various permutations of sound/silence and picture/no picture. These states are demonstrated in the editing, which cuts between them at regular intervals (determined by dividing a roll of film equally by the total number of combinations), with no regard for the audience struggling to follow the dialogue. The only images in Production Stills (1970) are a sequence of nine Polaroids placed in front of the camera. Taken and developed in real time, they show Fisher and the crew making the film itself.

Morgan Fischer

Production Stills 1970

© Courtesy Galerie Daniel Buchholz, Cologne

Standard Gauge (1984) is perhaps his central film, although its personal theme is by no means typical of his work. It begins with a scrolling text about the invention of cinema, explaining how 35 mm became the international standard gauge for film production, but soon shifts into an autobiographical account of a life in pictures. A narration begins over a blank (clear) screen with the story of his introduction to 35 mm motion picture film – a”short end” of unexposed camera stock given to him by a friend in 1964. A strip of film containing the “head” (beginning) markings of a reel of Jean-Luc Godard’s La Chinoise enters the narrow field of vision as Fisher describes how it came into his possession. He then shows fragments from trashy B-movies such as The Student Nurses (a Roger Corman production that he worked on) and Messiah of Evil (he was principal editor and had a bit part as gallery assistant to a deaf, dumb and blind art dealer), examples of nitrate film stock and the Technicolor dye-transfer colour process and “China girl” test shots used by the labs to correct colour balance (the cinema equivalent of the 1970s TV test card girl, and so called because the young woman featured usually wears a vaguely oriental dress). He also highlights numerous empty or abstract frames that suggest the work of visual artists such as Brice Marden, Barnett Newman and Ed Ruscha that he admires. Standard Gauge is a 35-minute found footage film, but its sequences are paraded in front of the camera in an apparently continuous take, rather than being edited together in the conventional manner. It is a product of its maker’s belief in the duality of cinema, and a refusal to devote himself exclusively to the avant-garde and forsake his appreciation of commercial movies.

In discussions about his work, Fisher draws reference to art history rather than to his film-making colleagues, citing influences such as Sol LeWitt, Marcel Duchamp, Ad Reinhardt, Susan Sontag and Yve-Alain Bois. It is no surprise, then, that he has long since led a dual life between cinema and gallery – his earliest film installation dates from 1977. His exhibition at Greene Naftali, New York, last year maintained a close relationship to cinema, being a series of mirrors cut to the proportions of various formats of film frames, ranging from Silent 1.33:1 to Ultra Panavision 70 2.76:1, but other shows have featured conceptual paintings. The most recent, at Adamski in Aachen, presented several “edge and corner paintings”. The dimensions of these triangular grey monochromes were dictated by the architecture of the gallery. One flat edge ran along the side of a door or skylight and the canvas then stretched out to a corner of the wall. Fisher directed how they should be made, but did not participate in their fabrication.

As well as his work for gallery spaces, Fisher’s films, which are certainly deserving of their current revival, examine the conditions of film production with candour and humour. Although they teach the viewer about cinema, they are much more than simple didactic exercises.” One thing my films tend to do is examine a property or quality of a film in a radical way,” he says. “Being radical is a modest form of being extreme. They each examine an axiom of cinema and say,’What if ?’”