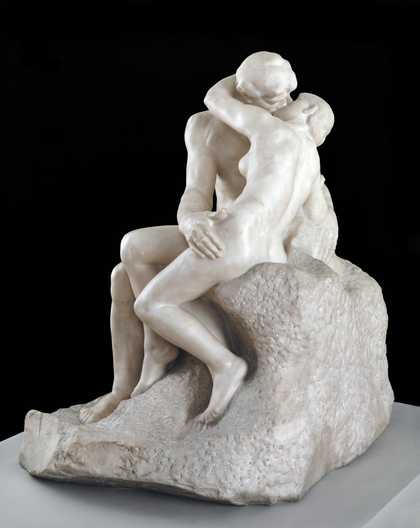

Auguste Rodin

The Kiss (1901–4)

Tate

Among the sights greeting visitors to Tate’s galleries over the years, one sculpture, titled The Kiss 1901–4, has proved a reliable favourite. Hewn from a vast block of marble, this monumental snog certainly draws attention to itself. Many who circle around this tangle of naked limbs discover a more private side to its allure, as they trace echoes of intimate encounters, recently enjoyed or only dimly remembered. Auguste Rodin’s classic celebration of passion provides a good starting point for exploring art’s relationship with romantic love.

The familiarity, even notoriety of The Kiss has caused us to lose sight of how the sculpture’s sensuality struck its first viewers. This couple was a hit from the moment that Rodin exhibited his primary, plaster and bronze versions in 1887. Several hundred casts and replicas ensued – produced at various scales to meet demand. The appetite for copies gives a hint of the excitement that Rodin’s eroticism, mild to our eyes, represented to his contemporaries.

The Kiss was not an amorous blip, but part of a tumultuous moment in the history of Western art when the forces of sexual attraction and arousal were acknowledged with new-found directness. Our gift for forging emotional attachments accompanied by the throb of physical desire is an ancient one. But it was not a side to human nature artists of Christian Europe raced to honour. Though there are touching exceptions from before the modern era, Western artworks censured more than they celebrated amorous feelings – sensual craving being recurrently linked to folly, vanity or carnal sin. In The Kiss, old scruples seem to fall away (along with the marble couple’s clothes).

Artists did not embrace amorous desire overnight. From the 18th century, successive artistic fashions introduced modes of exploring love that were less sternly moralising. Rodin’s symbolist contemporaries elevated sexual love into a universal principle, floating free of narrative particulars. If The Kiss leans in this direction, its literary source was a favourite text for Rodin’s artistic forerunners of the Romantic period. The lovers were originally named as Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta: a pair of 13th-century adulterers whose cursed spirits sigh out their pitiable tale in Dante’s Inferno. By the time the work became widely known, Rodin had dropped the historical identifications, accepting that the couple’s new fate was to embody a generalised concept of love.

No artwork can capture what love means for every viewer – let alone for all time. If historical costumes are discarded in The Kiss, the lovers are clothed in a sexual worldview that dates them nonetheless. Rodin fixated on heterosexual desire with an ambivalence common among European, male artists working near the turn of the 20th century: elevating it as a mystical life force while appearing perturbed by unconstrained female sexuality (it is Francesca’s snaky embrace that seals Paolo’s doom).

Since the sculptor’s chisel finished its work, our expectations of love and relationships have been repeatedly rewritten. Art of the last two centuries has kept pace with our ever-shifting outlook on matters of the heart and sometimes encouraged us to imagine new directions. If not all love stories received equal validation in the past, omissions and biases have goaded artists towards narratives once sidelined. The enduring popularity of The Kiss, meanwhile, is a firm indication that love – uplifting, compulsive, inspiring, dangerous and perennially seductive will never cease to reel us in.

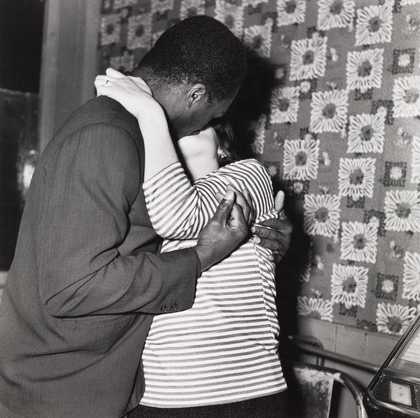

Bandele ‘Tex’ Ajetunmobi

Couple Kissing, Whitechapel, London (c.1960s, printed 2012)

Tate

Courting Trouble

These lovers caress in the sanctuary of an East End nightspot corner. At the time Bandele Ajetunmobi captured their tender kiss, many white Londoners were affronted by love that jumped lines of culture or ethnicity. In other spaces of the city, similar couples faced disapproval and racist animosity.

Arthur Lemon

The Wooing of Daphnis (exhibited 1881)

Tate

Making Eyes

The pastoral love story of Daphnis and Chloë hails from second century Greece but inspired a good crop of modern retellings. In Arthur Lemon’s tranquil painting the young protagonists fall under love’s spell. The cattle plodding in the background provide a quietly animated contrast to their stock-still human attendants, transfixed by their dawning mutual attraction.

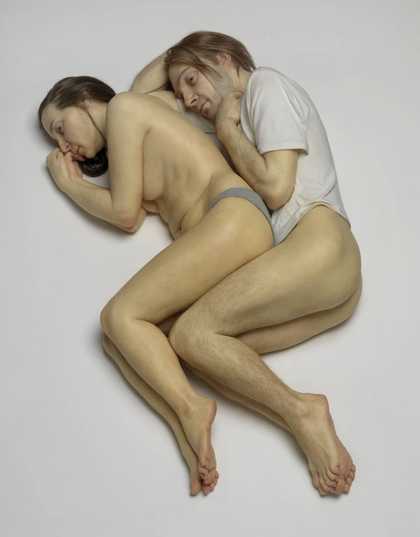

Catherine Opie

Melissa & Lake, Durham, North Carolina 1998

chromogenic print on paper, mounted on aluminium

© Catherine Opie, courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles

Tying Knots

In the late 1990s, Catherine Opie set out to alleviate a shortage of queer portrayals of family life. With her large format camera, she drove 9,000 miles across America visiting lesbian households. The solemn poses of Melissa and Lake reflect norms common in marriage portraiture, foreshadowing expanded possibilities for same-gender love. Marriage equality for US couples lay 17 years off.

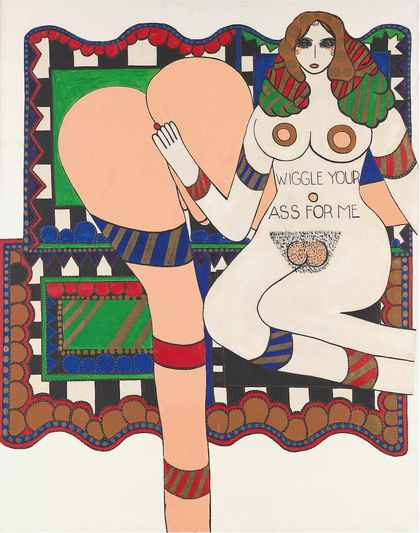

Dorothy Iannone

Wiggle Your Ass for Me 1970

acrylic paint on canvas, mounted on canvas

© Dorothy Iannone, courtesy Air de Paris

Getting Down

These frisky avatars represent artist couple Dorothy Iannone and Dieter Roth. The painting is from a series devoted to their sexual play, with captions that traverse erotic dominance, submission, humour and ecstasy. Betraying a lover’s fondness for myth-making, Iannone’s cross-cultural stylistic influences lend an air of near sacred significance to an earthly love story.

Wolfgang Tillmans

Für Immer Burgen 1997

chromogenic print on paper

© Wolfgang Tillmans, courtesy Maureen Paley, London

Holding On

Like the central band of an accidental flag, two hands link across hospital sheets. That belonging to artist Wolfgang Tillmans gently enfolds its paler, puffy companion, unwilling to let go. Jochen Klein succumbed to AIDS-related illness on the same day his partner’s camera preserved this ensign for lovers

Alex Pilcher is Senior Web Developer at Tate and the author of A Queer Little History of Art (2017) and Love (2019), both published by Tate Publishing. This article features excerpts from Love.