Olafur Eliasson and Lily Cole at Tate Modern, December 2018

Photo © Alexander Coggin

LILY COLE When did you decide to become an artist?

OLAFUR ELIASSON My father was an artist, so the idea of being an artist was something that I grew up with. After my parents’ divorce, I felt that I should do something so that he would like me. Gradually I got comfortable with drawing and that gave me a connection with him. I thought he was a great artist. He worked a day job as a cook on a fishing boat, but he also did all kinds of experimental art in the 1970s. He was obsessed with Robert Rauschenberg. I remember that we had a postcard of Monogram 1955 – 9 on the fridge. My father would try to explain to me this sculpture of the goat with a car tyre around its belly by talking about how culture and nature come together, and how industry would gradually ruin nature.

LC Was he proud of your work?

OE We actually collaborated on a few pieces together. For one, we developed an ocean drawing machine, where you would dip a ball in ink and then place it on a piece of paper. As the fishing boat rocked on the ocean, the ball would roll around the paper, creating a drawing. We had good fun making these drawings and called them our Ocean Drawings.

LC In your teenage years you got into breakdancing, which turned out to be quite an influence on your work, right?

OE In the early 1980s, when my friends were all into New Romantic music, I started listening to hip hop and rap music. Then I discovered the various dance scenes and started performing on the streets and on stage. That experience helped me to develop a relationship with space. Dance for me was about architecture, about understanding how movement and space are interconnected, and how that spatial relationship is a temporal relationship. So breakdancing is something that has stayed very dear to my heart. For me, moving through space is about making the space explicit to whatever narrative you choose.

LC Do you still dance now?

OE I do some movement exercises now and then, and when I am working on an exhibition I relate to the space in a very physical way. I memorise the size of the exhibition rooms by walking around the edges of the space, surveying the walls. I have an internal, physical map in my body, besides the plans and drawings that I can look at, the photos I take, and all the other ways of documenting space.

LC As your installations and other works are very experiential, do you see your work as encouraging the audience to move in a different way?

OE I like the idea that I’m asking the audience to co-produce the experience with me, so to speak. I create a machine or experimental set-up of sorts, call it a work of art, but it is the audience’s engagement that has the consequences.

Beauty 1993

© Olafur Eliasson

Photo: Maria del Pilar Garcia Ayensa / Studio Olafur Eliasson, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, CA, USA

LC What do you want from the audience? Are you hoping to give them something positive, or to challenge them in some way?

OE I like to encourage them to form a narrative or engage in a debate. I’m very interested in how we see each other in these spaces: Do I feel comfortable? Do you? What’s the structure and nature of the situation in the space? The whole architecture is part of it, as is the museum’s DNA, even its brand. You cannot say that the larger context is unrelated to the artwork.

LC Which makes architecture feel like an inevitable development of your work. I loved your most recent building: the Fjordenhus in the Vejle Fjord, Denmark.

OE I now have an architectural office together with Sebastian Behmann, called SOS – Studio Other Spaces. And my interest in architecture has a lot to do with how we shape the world we’re going to live in in the future. For me, Fjordenhus or the buildings in the Meles Zenawi Memorial Park in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia that we are currently working on, are ‘slow buildings’, just as they are, in a sense, artworks that you can live in, or work in, or go to school in. These projects, like my artworks, have a lot to do with dance, time and movement.

Fjordenhus, built in 2018, designed by Olafur Eliasson and Sebastian Behmann with Studio Olafur Eliasson.

Photo: Anders Sune Berg, courtesy Studio Olafur Eliasson

LC Do you consider your work very communal, and feel that this community is necessary for its function?

OE Sharing an experience, embracing the communal nature of how we make meaning of something, often amplifies and alters that experience. At the same time, I can see the quality of just having time to look at one painting, for example, where slow looking and contemplation are important. Museums should facilitate that need too.

LC Community also seems to be central to your working practice: what is your methodology for collaborations?

OE I find the discipline and structure of working with others to be very inspiring. I have an amazing team at my studio in Berlin. Frankly, I hire people to take care of those things that I’m not so good at, and I take a similar approach with collaboration. For example, with Ice Watch, which was recently installed in London outside Tate Modern and at Bloomberg’s European headquarters, I worked with a geologist from Greenland, Minik Rosing, who has an outstanding knowledge about glaciers and the climate. I get excited about collaborating. Art can connect many people from different disciplines: scientists, politicians, members of NGOs or someone from a community project.

LC What did you hope to achieve with Ice Watch?

OE By bringing these massive pieces of glacial ice to the centre of an important global city, like London, I wanted to give people an opportunity to come into direct contact with the reality of climate change – to see it, touch it, smell it. I am hopeful that this experience will, in turn, touch people, and that the conversations that arise from the work will, in some measure, motivate people to take action in response to climate change.

Ice Watch 2014 outside Tate Modern, London, 2018

Photo: Justin Sutcliffe, courtesy of the artist; neugerriemschneider, Berlin; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles

LC One consistent theme in your work has been the environment. Where did this interest begin?

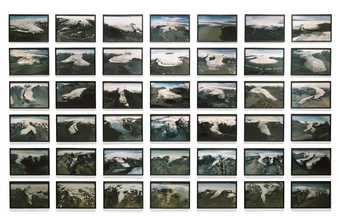

OE I used to hike in Iceland during my holidays, and then, about 20 years ago, I photographed the glaciers there from the air. At the same time, as an artist, I had long been interested in the dematerialisation of conventional sculpture. This led me to work with atmospheric conditions, and things that are relatively abstract – water, fire, light, fog. And I was exploring what effects context and surroundings have on a work and vice versa, viewing them as a system that is deeply interconnected. From there it was a short step to the environment – to how our small, individual actions and choices have consequences for the system of the climate.

Olafur Eliasson The Glacier Series 1999

© Olafur Eliasson Photo: Photo: Jens Ziehe, courtesy the artist; neugerriemschneider, Berlin; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles

LC At what point did your concern for the environment become a political conversation?

OE After The Weather Project at Tate Modern in 2003 [known to most as the ‘Sun’], I realised that all the things that I had been interested in up until then were related to the climate.

LC Do you believe that art has the power to impact political policy?

OE The Weather Project was a collective project to a large extent. It had a lot to do with how all these people came together and co-produced their shared experience, which led me to think quite a bit about public and civic engagement. In a city like London, public space has been privatised to such a large extent that I think a lot of people claim the cultural space of a museum like Tate Modern as a public space in the most positive sense. I’ve long been interested in what culture can bring to society, and I’m totally convinced that art has a significant role to play. Even though culture is often marginalised, pushed to the periphery, it is up to us – artists and cultural institutions – to claim space at the heart of society. Culture is where identity, history and belonging are evaluated and formed, although this is not necessarily done in an advocacy type of way, but on a contemplative, spiritual, deeply emotional societal level – both individually and collectively.

Olafur Eliasson Little Sun 2012

© Olafur Eliasson Photo: Photo: Xaver Kitzinger

LC I loved the activism and pragmatism behind your solar energy project Little Sun, with engineer Frederik Ottesen. Can you tell me more about this?

OE I have visited Africa often over the years, especially Ethiopia, and I have seen how a lot of people there use dangerous and expensive fuels to light their homes at night. Around eight years ago, Frederik and I developed a solar lamp that we could bring at a fair price to people in areas of the world without consistent access to the electrical grid. So far, we have delivered more than 800,000 Little Suns.

Olafur Eliasson The New York City Waterfalls 2008

© Olafur Eliasson

LC When I looked over the history of your work, the scale of your projects seems to have increased over time, in parallel – and, arguably, as a consequence of – your success. Was that ambition for scale there from the start?

OE I worked as an artist’s assistant in New York in 1999, when the art market had crashed, so when I came out of art school, I had no expectations of success whatsoever. I was very humble and very thankful for what I had. I have always been very interested in democratising access to culture, since art, I believe, can host a participatory element that society otherwise has difficulty accepting. There is a lot of polarisation in society in general – in politics, for sure – but a museum has a certain trust and autonomy that allows it to be relevant in larger cultural debates. It can work a bit like an informal, decentralised parliament, and offer shared experiences. So, my interest in working large-scale was not just because I wanted to do something big, but because this was closer to what we could call the civic level. I am interested in the question of ‘we-ness’ in Europe for instance. I have asked the question: why has Europe failed to give me an emotional narrative that I can identify with? There needs to be an emotional narrative to the idea of ‘we-ness’ in Europe that allows people a sense of shared identity. Such an approach seems important in the recent Brexit conversation.

Olafur Eliasson Your Spiral View 2002

© Olafur Eliasson Photo: Jens Ziehe, courtesy Boros Collection, Berlin, Germany

Olafur Eliasson Big Bang Fountain 2014

© Olafur Eliasson Photo: Anders Sune Berg, courtesy the artist; neugerriemschneider, Berlin; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles

LC I read that you were surprised by the outcome of the British referendum.

OE Yes. I think it’s fair to say that we, the cultural sector, are partly responsible for the sense of alienation that led a lot of people to vote against Europe. A lot of people do not feel that they are being heard, and we have not adequately responded to this challenge. In the cultural sector I think we make the mistake of claiming to be this moral compass for society, but often fall into the trap of being arrogant and elitist. We are caught in an echo chamber, a closed circle.

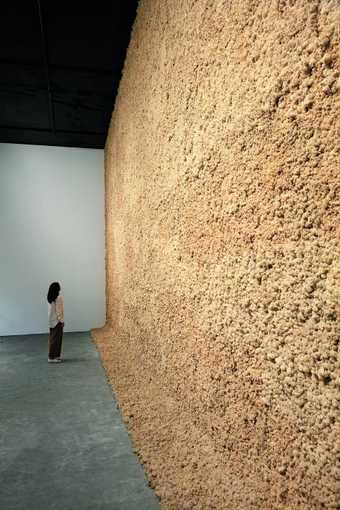

Olafur Eliasson Moss Wall 1994

© Olafur Eliasson Photo: Hyunsoo Kim, courtesy the artist; neugerriemschneider, Berlin; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles

LC You have used the word ‘spiritual’ in our conversation. Are you spiritual?

OE Well, I think we need to have space for things that are not easily verbalised. The Enlightenment threw out anything to do with mysticism, with hurly-burly religion, etc., and people became fixated on a certain more rationalist, empiricist approach to the world. These changes brought us to where we are today, but they also took away space for imagination or for emotional presence. I would say I would like to maintain a certain space for these things – and you could call it a spiritual space, if you like.

Olafur Eliasson: In Real Life is at Tate Modern 11 July 2019 – 5 January 2020