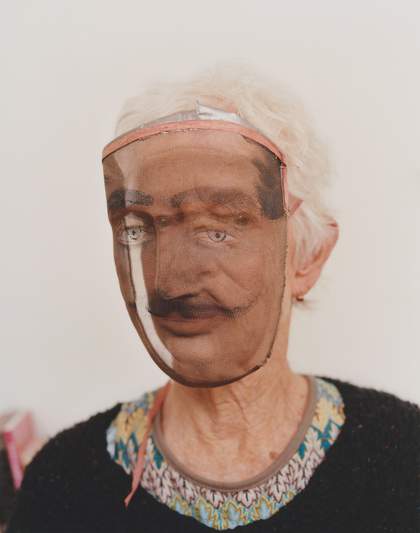

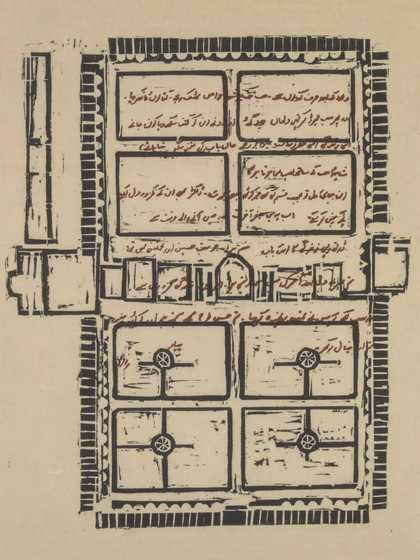

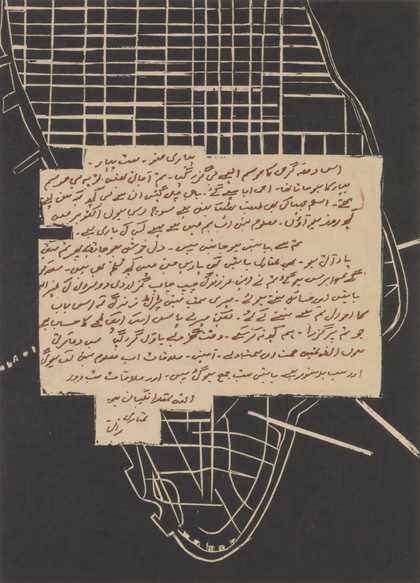

Letter written to Kamila Shamsie’s maternal grandmother in Karachi, Pakistan by her sister in Rampur, India, c.1950s

Courtesy Kamila Shamsie

This seems as good a place as any to admit to my problem with museums. When I say ‘my problem with’, I don’t mean that there’s something problematic about museums; I mean, I have a problem. I’m a reader. I always have been. But I don’t just mean a reader of books; I mean, a reader of any scrap of text I see lying anywhere. If I’m watching a movie in English with subtitles in a script I understand – even if I don’t understand the language – there I am, reading the subtitles. Put me in a car and drive me through a new city and I’m likely to be unable to tell you that we passed by parks or skyscrapers or gargoyles, but I will tell you the slogans on the billboards, the names on shopfronts, the wording on road signs telling you of all the perils that may lie ahead. This becomes particularly problematic in museums, where I can walk into a room of Blakes or Souzas or Hepworths and find myself drawn immediately to the wall text telling me things about the artworks I am failing to look at while I read every word written about them. This is not a case of wanting to read the explanations and interpretations before I take in the art; when I remember to force myself to do it correctly – and by correctly, I mean in the manner I find most satisfying – I’ll first look at the work, think about it, or feel about it, and then go to the wall text, and then back out to look at the artwork again. That is how I want to approach museums. But that reading compulsion can, at its worst, make me go from one bit of wall text to the next, with a mere glance at the artwork ‘in between’. I’m slightly exaggerating. But not entirely.

And that is why it strikes me as so very strange that in all the years during which I grew up with a framed letter hanging on the wall of my house, I never stopped to read it. It is a letter written to my maternal grandmother in Karachi from her sister in Rampur, at some point in the 1950s. A decade or so earlier, a letter written between sisters living in those two cities would have been a quite different kind of object; but after 1947 it was a letter sent across the new border separating India and Pakistan, a post-Partition letter between sisters who had grown up in a pre-Partition world. My grandmother had two sisters and three brothers – she and one of her brothers moved to Pakistan after Partition; the others stayed in India. Though my grandmother was never one to live in regret, I always knew how much she missed her sisters in particular. The divided family, the visa regimes placed between them (which none of them had imagined would come to pass when Partition first took shape), the weight of the words ‘Indian’ and ‘Pakistani’ separating the siblings into different categories – I grew up recognising the strangeness and the weight of all this. And this letter from my great-aunt came to symbolise for me both the continued closeness and the separation between my grandmother and her sister, which stood in for the continued closeness and separation between all the divided families of Partition.

In the time between starting to write this piece and now, as war talk and military action is turning more worrying between India and Pakistan, the letter has also come to symbolise even more starkly how this intimate familial tone is the very opposite of the language in which the two nations address each other – increasingly, not just at the official level but also at the level of its people who are now growing up with no links across the border, no memories of a time before separation.

So, why didn’t I read it? I do read Urdu, lest anyone think that’s the reason. I think my not-reading had to do with the fact that I thought of this letter less as a letter and more as a work of art. It is written, by the way, in rhyming couplets and in the beautiful calligraphy of a scribe’s hand (my great-aunt was a rather grand lady; there were scribes to write out her letters). The fact it was in a frame, with its lines so aesthetically balanced and rendered, and that it hung in a hallway beside other works of art made it possible to move it from letter-world to art-world. It was a piece of art that symbolised Partition and separation and closeness and the history of my family and my nation and my region – and it symbolised those branches of the family that had become untwined, so that though my grandmother continued throughout her life to write weekly letters to her other sister, and though my mother had grown up with family visits to India and knew all the aunts and uncles and cousins, by the time of my generation, with all the political hostility between the two countries and the difficulties of visa regimes, that entwining had disappeared almost entirely.

I think I’m lying when I say I didn’t read the letter. I suspect I read the first couplet or two – words of greeting, saying things like ‘my dear sister, I received your lovely lovely card’ – well, that didn’t begin to carry the weight of everything the letter represented, so better to leave it unread, to allow it to be a work of art that symbolised so much that a mere letter couldn’t say. All those couplets: India and Pakistan, sister and sister. The meaning lay in the form, not in the content. And the letter itself seemed to know it – look at it: this was always an object meant to be framed, rather than read and re-read, becoming smudged with thumbprints and tears. It certainly wasn’t meant to be eventually folded up and placed in a file somewhere.

I have now read it, in case you’re wondering. I read it for the first time last week when working on this text. It’s filled with the sorrow of separation, as well as closeness and shared lives. Talking about her forthcoming birthday my great-aunt says:

Kya manai’ ab aisee salgira

Tum nahee jub to kaisee salgiriHow should I celebrate my birthday?

Without you here what kind of birthday is it?

Except she does it rather more beautifully, with a lovely rhyme and rhythm to it.

Reading it, it struck me as strange that someone whose life is so centred around the power of words should have looked away from words. Was it just my great-aunt’s language that I thought wasn’t up to the challenge of conveying everything the letter symbolised, or was it language itself that falls short?

It is worth mentioning here that it’s widely believed that the greatest piece of writing – indeed, the greatest piece of art – created about Partition is a short story, called ‘Toba Tek Singh’, just a handful of pages long, by the Urdu writer Saadat Hasan Manto. The story is about the (and I’m using the language of the time) inmates of a lunatic asylum in the district of Toba Tek Singh, near Lahore. When Partition takes place, the lunatics must be divided between India and Pakistan. It ends with one of the inmates lying down in no man’s land, muttering nonsense words: ‘Upar di gur gur di annexe di be-dhiyana mung di daal of di Toba Tek Singh and Pakistan’. A rough translation would go: ‘Upstairs the rumbling the annex the heedlessness the lentils of Toba Tek Singh and Pakistan’. A man speaking nonsense words in a world where reality is beyond what words can convey – that is part of the effectiveness of this story. The Partition of word and meaning. The inability of language to make sense of what is going on, except through conveying senselessness.

It is certainly true that sometimes the linearity of language, the logic of first this-then this-then this, words become sentences become paragraphs – sometimes that seems too neat, too false, to convey a shattering, a sundering.

I’ve felt this in my own writing. Some years ago, when writing about the dropping of the atom bomb on Nagasaki, I knew the moment of the bomb detonating could only be depicted by two blank pages – the closest thing to a flash of white light I could put on a page.

If I had to invent a story about my life as a writer leading up to the moment of those two blank pages, it would start with me looking and looking at that framed letter on the wall and choosing not to read it. That was the moment when I first knew that sometimes words are not what you need to convey the weight of a particular kind of moment.

Bruce Nauman

Raw-War (1971)

Tate

As a writer it’s hard not to be drawn to considerations of how text functions in art – I’m particularly interested in how it functions around events that seem to leach the meaning out of everyday language, or else make every word so freighted that it collapses under its own weight. What are words when you don’t use them to convey their literal meaning, but find a way to burrow down into them and find the symbolic heft of them instead?

Take, for instance, Bruce Nauman’s Raw-War, a lithograph from 1971, during the Vietnam War. Nauman is, of course, well known for his use of language and text – this was the first word-image print. You look at this work, and certain things start to happen in the brain without your even thinking about how or why they’re happening. The most obvious, of course, which doesn’t require you to look at the title of the work, is the word WAR becoming the word RAW. Two of the three letters of WAR look the same forwards or back – the third R is inverted in the red front image – our left-to-right reading of English makes us start at W, then read A, then R. But the backward shape of R suggests we’re reading a mirror image and we need to go in the other direction: R, then A, then W. The stark redness against the black background does its work too – if it had been some other colour, would the word associations come up so quickly? Raw Meat, Raw Wounds. Certainly, my experience of the work is that by the time you think those words, you’ve already felt the discomfort of them when brought together with the word WAR. And the outlines of the letters behind, they do something to us as well. There’s a reiteration, a repetition; the details change, the outline doesn’t. WAR. RAW. RAW WAR. Again and again. A letter turned on its axis is the world turned around, the natural order subverted. Look closer at the scratchings in the background: they are crisscrossed, barbed wire; I found myself physically wincing when my attention honed in on the gleaming sharpness of the white etchings. At some point I start to think, raw emotions. Later, raw materials – which is to say, material in its natural state, yet to be fabricated into something else. Is war our natural state? Is everything else fabrication?

All these are the responses of which I’m consciously aware, but there is also, of course, the emotion – the incredible discomfort and sorrow I feel looking at this – which intensifies the longer I stare into it. It does feel like a staring into rather than a staring at.

Nauman himself said, ‘I am really interested in the different ways that language functions. That is something I think a lot about, which also raises questions about how the brain and the mind work – the point where language starts to break down as a useful tool for communication is the same edge where poetry or art occurs.’

I did balk at this idea of poetry starting in the same place where language breaks down as a tool for communication, and yet I understand what Nauman means when he says: ‘When language begins to break down a little bit, it becomes exciting and communicates in nearly the simplest way that it can function: you are forced to be aware of the sounds and the poetic parts of words.’

Reading this, I was reminded of my adolescent self, obsessed with turning words into anagrams and saying words backward. It pleased me endlessly that the letters of my name could be reconstituted into the intriguing phrase ‘Miasma Like Ash’. There was a time I could have recited backwards much of ‘To be or not to be’ – or should I say ‘Ot eb ro ton ot eb’. Of course, what I was doing as an adolescent obsessed with reading, already determined to be a writer, was trying to work my way around the idea that there is more to language than its literal meaning, that words have an almost ineffable power, and that, perhaps, by flipping them around and turning them inside out I could understand that power better.

It’s a peculiar contradiction. Words have an extraordinary power, beyond what should be possible for a few squiggles on a page. How can the four letters of H-O-M-E convey all that they convey? Does it help you answer that question if you understand that they’re an anagram of OH ME? Probably not, and yet it remains a pleasing thing to know. So yes, words have an extraordinary power beyond what should be possible for a few squiggles on a page. But when you place words together in a sequence it can happen that the logic of sentences goes against the illogic of what those sentences are trying to convey – which is why the man saying ‘Upar di gur gur di annexe di be-dhiyana mung di daal of di Toba Tek Singh and Pakistan’ conveys more about Partition than any great tome on the subject. When the logic of sentence formation starts to contradict the illogic of what is being conveyed in those sentences, it can become fruitful to separate words from logic and send the words into a space where they can work at a symbolic, suggestive, allusive level. When colour and shape and depth and crossing out can force our brains into making connections in a way that the language sequencing of sentences doesn’t allow for.

I am not trying to create too great a gulf here between the work of someone like Nauman and the work of a prose writer. Chapter breaks, paragraph breaks, sentence breaks all function at a visual level creating certain effects. As much gets said in the spaces between words as in the words themselves. And language is constantly asking us to bring our own ways of seeing the world into our interpretation. That’s why people can love the same book and interpret it in very different ways – it’s why I’m sometimes taken aback by the interpretations people bring to my own work. People who love the books interpret characters in ways which I know don’t come from any of the sentences on the page, but from the spaces in between sentences, which allow – which must allow – readers to fill in the words that are unwritten.

The best writers are almost always the ones who allow the readers’ brains to do the most work, making connections between things, filling in the gaps, visualising in colour and motion things that remain unwritten, feeling the emotions that are never spelled out. When I talk about artists who use text but make it do something other than convey the literal meaning of the words on the page, I am not setting them apart from writers – I’m speaking of them as extending some of the work that writers already do.

One of the artistic works I find particularly moving – and effective – in its engagement with text is Mona Hatoum’s video Measures of Distance 1988. It’s a 15-minute-long piece and certain elements of the artist’s biography become clear as the video progresses. Mona Hatoum was born to a Palestinian family that was forced to go into exile before Hatoum was born; the family was splintered, moving in different directions – Hatoum’s parents were among those who went to live in Lebanon. She was born and grew up in Lebanon but very clearly identifies as Palestinian. In 1975, she was in London when civil war broke out in Lebanon, and she became a double-exile, a Palestinian from Lebanon living in London.

Measures of Distance starts with a blank screen, which, after a few seconds, gives way to the image of a grid of lines, on which we see lines of Arabic script. The idea of distance comes immediately into play in your response to this shot – I’ve read more than one piece of commentary that says it looks like barbed wire. I can see that it does, if you don’t know what it is. But if you read the script, it looks like words. What the words say, I couldn’t tell you; I know the script because it’s much the same as the Urdu script, but I don’t know the language.

It is, of course, one of the obvious things to be said about the way text can function in art – it can serve a purpose even for those who don’t read the language at all. Sometimes, the person who can read might miss something in the way the text is working on a less knowing viewer: because the reader sees the words, rather than the shape of the words, they don’t think that this video installation, which will be in part about war and separation and barriers, starts with words as barbed wire. Or perhaps the viewer who is seeing Arabic as barbed wire is actually projecting a prejudice towards the language onto the way they see it.

Another thing that my reading around this piece revealed to me is that many people think of the sheet of words as a veil – I didn’t think of a veil. But once the camera moved back enough to allow me to see what was going on, I did think, ‘shower curtain’.

Words and shower curtains, or barbed wire and veils – how have people’s perceptions of this changed over the years? The artwork was created in 1988. I suspect that, in the decades since then, even more veils and barbed wires have entered people’s seeing of a Palestinian artist’s work, assuming the people doing the seeing are located in this part of the world. Or perhaps that’s just what I’m reading into other people’s readings of the text on the screen.

The words of text are from letters that Mona Hatoum received from her mother in Lebanon. The images on the screen are pictures that Hatoum took of her mother when visiting her in Beirut in 1981. In addition to the two visual layers, there are two aural layers: taped conversations between mother and daughter, in Arabic, during that 1981 visit. And Mona Hatoum’s voice reading out loud the letters from her mother in translation, in English.

The letters talk of war, of sexuality, of exile, of absence, of family, of the female body. What Hatoum achieves with the layering of the visual and the aural is to bring us closer to an experience of receiving such letters from your mother who is very far away while, also, creating different kinds of layers of distance – the sense of distance will vary from viewer to viewer, depending on your relationship with the Arabic language, the English language, the Arabic script.

Sometimes when the camera is close up to the letters you can see them more clearly, but there are only a few words on the screen and the sense of fragmentation is acute. Other times you can see more of what it written, but even this is partial and some words are lost in light and shadow. And when the things being spoken of are particularly bleak, darkness overtakes much of the screen, the camera pulls back even further, and the words are completely indistinct.

We do know something of what the letters are saying because of Hatoum’s voice translating them for us. But more importantly we know what is lost in the space between the woman writing the letter and the woman receiving it, thanks to that thing that the written word sometimes struggles to convey: tone. The tone of Hatoum’s voice, as she’s reading, is almost completely flat. This is a striking contrast to that other aural layer of mother and daughter talking together in Beirut in – I’m told – colloquial Arabic. You can hear the intimacy in their voices, as they move from questions to serious matters to things that make them laugh, often with more than a touch of bawdiness. Only people with the closest relationships talk to each other in that way – and it also occurred to me, as I listened, that there seemed something familiar in the tone of their voices, not from my life in England but from my life in Pakistan. I thought I recognised a kind of way in which women speak to each other in deeply patriarchal societies when they know their conversations are transgressive, and could never exist outside this intimate space of trust.

And then there is the darkness – it is there at the very start of the video before text and image and light and ultimately sound emerge from it. Eventually the darkness moves back and finally takes over the screen entirely. The last minute or so is just a blank screen. When the screen turns black, and both the written text and the images of her mother are lost, we also lose the conversational soundtrack of mother and daughter. All that is left is Hatoum’s voice reading out the final letter from her mother explaining that the local post office was destroyed by a car bomb, and the nearest post office is in an area she doesn’t like to go because of the frequency of rockets falling there, so, although she is getting this letter out via a relative who is travelling out of Lebanon, there will be no further letters after this one. The disappearance of all those other layers we’ve become accustomed to – the letters of text on the screen, the images of her mother in the shower, the conversational voices – their disappearance really creates a sense of life going out of the world.

The last thing Hatoum reads out loud before all the other layers are stripped away is this line from her mother’s letter: ‘When you talk about a feeling of fragmentation and not knowing where you belong, well, this has been the painful reality of all our people.’ And then the screen goes black, and the voices speaking in Arabic disappear.

Fragmentation is at the heart of this artwork – the fragmented text, the fragmented voices, the fragmented images. But fragments can be very meaningful. When they go, those fragments we have been living with for the duration of the piece, so much is lost. And finally, Hatoum’s voice stills too and there is only the darkness, filled with absence.

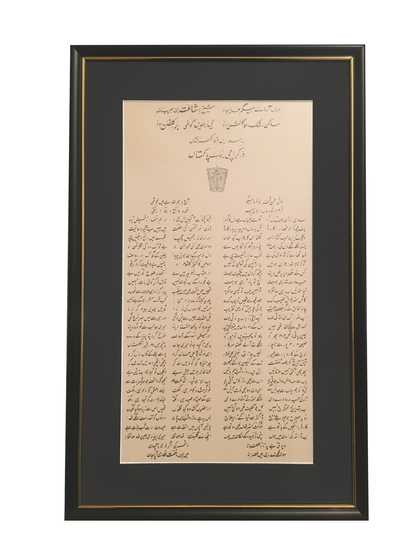

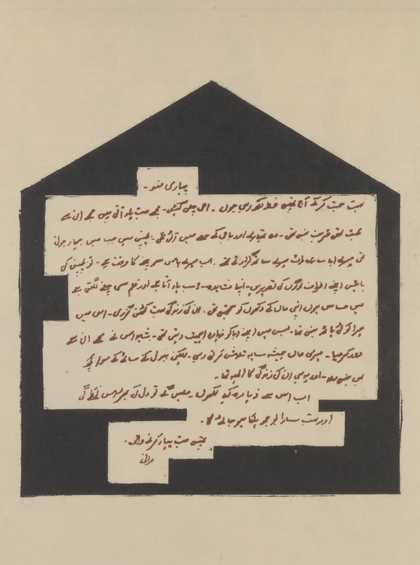

The first print from Zarina Hashmi’s Letters from Home 2004, eight woodblock and metalcut prints on paper, 57 x 38 cm each

© Zarina Hashmi

The letters in Measures of Distance were really letters, written by a mother to be sent to her daughter. There is a different kind of letter in the Indian artist Zarina’s Letters from Home from 2004. Tate describes some of the basic details of the work: ‘Letters from Home is a portfolio of eight monochromatic woodblock and metalcut prints, produced using original letters written in Urdu to Zarina Hashmi by her sister Rani. From the letters, the artist made printing plates which she used to print onto handmade Kozo paper. The letter imprint was then surrounded or overlaid by the outline of a house, a floor plan or the map of a geographical location, using a woodblock print.’

Zarina (aka Zarina Hashmi) was born in pre-Partition India and grew up in Aligarh. The events of Partition made her family leave for Pakistan, losing their family home in the process. Zarina continued to live in India until 1958, when, aged 21, she left India with her husband, whose professional life entailed a great deal of travelling, and she hasn’t had a country to think of as home since. Discussing the Letters from Home series, she said, ‘my sister ... will always be my home.’

Rani’s letters were written from Pakistan to Zarina in whatever country she was in at the time. Although, not exactly. Rani wrote the letters and never posted them. Instead, she carefully collected them, and when she saw her sister she would hand over all the letters she had written in the time they’d been apart. That could be years. So, though these letters are written in a period of separation, they anticipate their own delivery to the recipient occurring when that separation has ended, even if only briefly.

It raises the question: how much is our understanding of what a letter is contingent on the letter as a physical object that travels between two people who are in separate spaces? Or how much is our understanding of what a letter is contingent on it being written in a particular moment and sent on its way in that moment, even if it may not arrive for a while? Take both these elements away and what kind of letter is a letter?

Perhaps it’s no surprise that the tone of the letters sometimes becomes more like one of a diary – if you know the person you are writing to may not receive your letters for some years, then eventually you may start writing as though primarily to yourself. On the other hand, the blurred edges of letter/diary are also a way of acknowledging that the person to whom you’re writing is so much a part of yourself that the distinction between Self and Other is blurred from the outset.

What I’m suggesting here is that something in the nature of these letters, from the very point of their origin, wanted to be something else, something not-quite-letter. In addition, of course, as is the case with my great-aunt’s letters to my grandmother, the letters between Rani and Zarina were not just about the words on the page, they were also about Partition and family and closeness and separation and all that was lost when one nation became two.

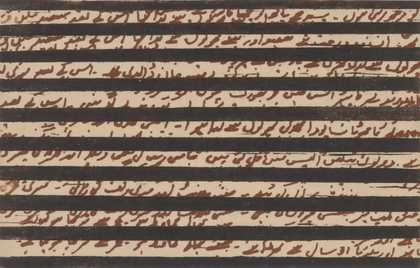

That Zarina doesn’t intend Letters from Home to rely on anyone reading the text is evident. In the first of the series, the letters are smudged, hard to read, and each line is printed in duplicate – it suggests double vision. When we look at the world, each eye creates its own image and the brain works to bring them together in a single image, but here that process has broken down, the two eyes aren’t working together. Are we as viewers failing to bring into a single image the two things we see here – letter by Rani, art by Zarina? We don’t yet know how to read the two together.

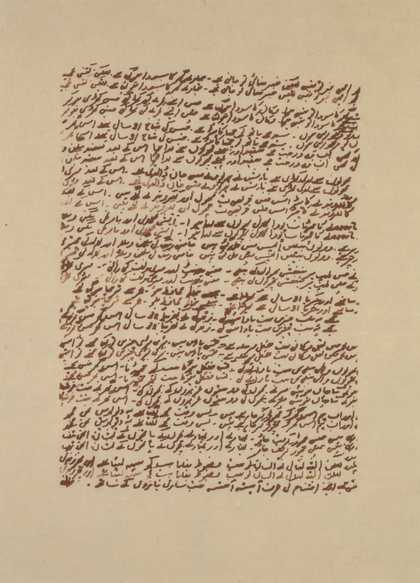

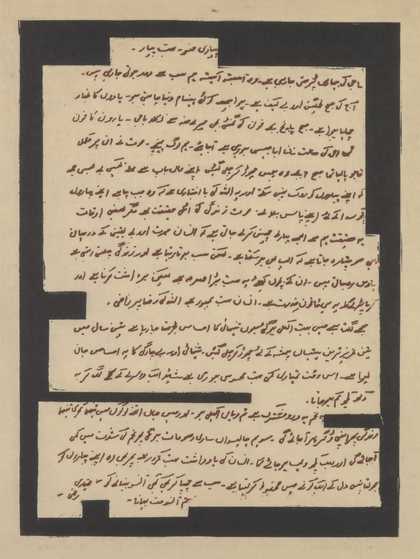

The second print from Zarina Hashmi’s Letters from Home 2004, eight woodblock and metalcut prints on paper, 57 x 38 cm each

© Zarina Hashmi

In the second letter of the series, the word in Urdu at the bottom right says ‘Aligarh’, the name of the city Zarina grew up in before Partition separated her from her childhood home. As a child, she once went up in a plane with her father and saw the city spread out beneath her; years later, she herself piloted a glider. The bird’s-eye view of Aligarh in the map printed over the words both captures something of the place that was home and gestures towards her distance from it. It’s also a memory of a childhood experience, before the world turned on its head.

The third print from Zarina Hashmi’s Letters from Home 2004, eight woodblock and metalcut prints on paper, 57 x 38 cm each

© Zarina Hashmi

One kind of map or the other comes up in most of these works – city maps or floor plans. Among the eight prints is a plan of Aligarh Muslim University where Zarina’s father worked, and which was a very significant part of a world of Indian Muslim culture that was largely destroyed by Partition, to the point that the language Zarina is writing in – Urdu – which was considered a Muslim language is one that is increasingly being moved to the margins in India. Both the Aligarh images – the city map and the university plan – are created using Rani’s words as a sort of base layer; now that the home that was Aligarh has been lost, the only way it can be kept alive for Zarina is in the interaction of these two sisters who lived together in that place, in a country that no longer is, in a house that they no longer have any legal claim on. What remains of her life in Aligarh is her companion in that life.

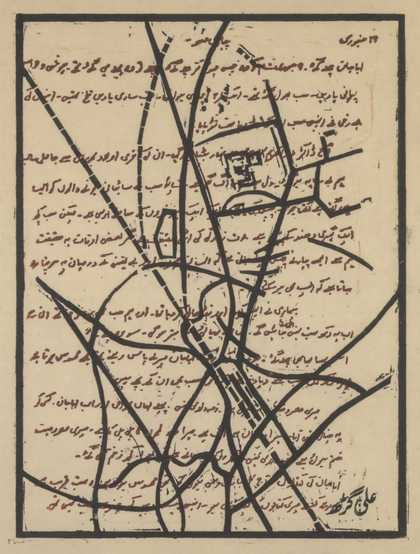

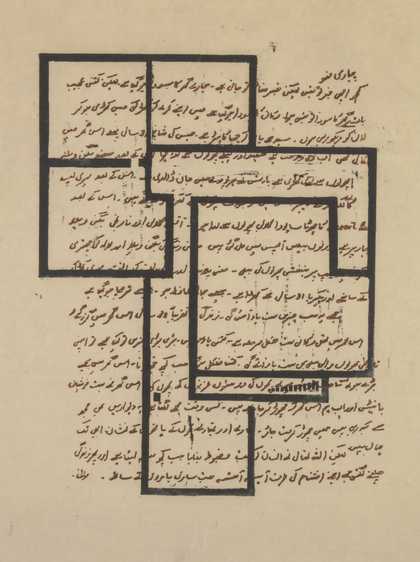

The fourth print from Zarina Hashmi’s Letters from Home 2004, eight woodblock and metalcut prints on paper, 57 x 38 cm each

© Zarina Hashmi

Unlike some of the images, the fourth letter of the series is not very blurred – it doesn’t have maps or floor plans overlaid onto it. This is the letter Rani wrote to Zarina telling her their mother – who she calls Ami – had died. Some of it is quite hard to read, but with enough concentration you can make out most of it, and the brain fills in the gaps created by illegibility. ‘I finally have time to sit and write. Ami has gone.’ The letter goes on to talk about the fact that she was never very close to her mother. Her greater closeness was to her father.

She doesn’t say ‘our’, she says ‘my’ when referring to their mother, which is what partly gives it that feeling of a diary rather than a letter – she is writing primarily to herself. She says ‘Meri ma hamaisha saaya talaash karti rahi.’ (You should know the word ‘saaya’ means ‘shade’. Think of the importance of that word in very hot parts of the world to understand that ‘saaya’ literally means ‘shade’ and metaphorically means ‘protection’.) ‘My mother was always searching for shade.’ It goes on: ‘But she never felt the shade or the breeze that moves through it.’

This lack of protection in their mother’s life came from the loss of the family home at Partition. Their mother would talk often about not having a home of her own. So Zarina has taken this letter which brings news of her mother’s death and built around it a house for her mother. Which is also of course a black border, signifying mourning. There is both loss here and restoration.

The fifth print from Zarina Hashmi’s Letters from Home 2004, eight woodblock and metalcut prints on paper, 57 x 38 cm each

© Zarina Hashmi

The sixth print from Zarina Hashmi’s Letters from Home 2004, eight woodblock and metalcut prints on paper, 57 x 38 cm each

© Zarina Hashmi

The seventh print from Zarina Hashmi’s Letters from Home 2004, eight woodblock and metalcut prints on paper, 57 x 38 cm each

© Zarina Hashmi

The eighth print from Zarina Hashmi’s Letters from Home 2004, eight woodblock and metalcut prints on paper, 57 x 38 cm each

© Zarina Hashmi

In the last of the series, it is like trying to read through a horizontal grid. There is something unpleasantly officious about the heavy black straight lines – in contrast to the cursive flowing script. Not quite a censor’s blackout, but with a suggestion of it. Is this the world of officialdom that keeps apart those who are officially Indian nationals and those who are officially Pakistani – never mind that they are sisters, never mind that they are each other’s home? Again, this seems so much more weighty: at the time of writing, India has made moves to try to get Pakistan expelled from the world of international cricket; Pakistan has banned Indian movies from being shown in Pakistan. It has been near impossible for the last couple of years for Pakistani writers and artists to get visas to India – moving in the opposite direction from India to Pakistan has been easier, but that’s probably going to change with the escalation of recent military action. The official hand is trying to erase all contact, all exchange, between the two nations.

Some lines of the letter are visible, some blacked out. Not everything survives, not everything is lost. Look at Letters from Home with no knowledge of the background to the piece or the Urdu language and there is so much you can still be drawn into and start to piece together. The double vision of the first letter, the officious lines drawn through the last. A map of Manhattan – and, before that, the map of somewhere distinctly not Manhattan. The floor plans. The words encased in the black border of mourning that is also a house. And the one thing that pulls it all together – the handwriting that belongs to the same person across each of these eight letters from home, a handwriting that becomes more central, more foregrounded as we proceed through the series. You don’t need to read a word of Urdu to know that the person who wrote those letters, and the fact of separation from her sister, is at the very heart of this work – and without her letters, none of this would exist at all.

The artworks mentioned here are in Tate’s collection. Bruce Nauman’s Raw-War was purchased in 1992, Mona Hatoum’s Measures of Distance was purchased in 1999, and Zarina Hashmi’s Letters from Home was purchased with funds provided by the South Asia Acquisitions Committee in 2013.

Kamila Shamsie is the author of Home Fire, which won the Women’s Prize for Fiction, was shortlisted for the Costa Novel Award and longlisted for the Man Booker Prize. She grew up in Karachi and now lives in London.

The Writers on Art series invites the best contemporary writers from around the world to produce new work on art and visual culture across Tate platforms. It is a collaboration between Tate Etc., Tate’s Public Programmes team and Tate Digital.