Gillian Ayres at her home studio in Gooseham, Cornwall, 2004

Photo: Jim Wileman / Alamy Stock Photo

Back in the 1960s, a member of Tate’s staff asked Gillian Ayres (1930–2018) if her abstract paintings related to the natural world around her, as was the case with some of her artist contemporaries. Her response, which took the form of a list, was wonderfully eclectic: ‘Crivelli, jelly moulds, Mrs Beeton’s ice cream and cakes, finials and crockets, lichens and seaweeds, shells, Uccello hats and plumed helmets.’

Such a joyous blend of the artistic, the man-made and the natural made perfect sense to those who knew her as generous and jolly, and still does to those who now view her paintings. As many have found, they are works filled with the energy of a mind that never tired of looking at the world around her, from the most beautiful piece of art to the most mundane of household items.

Ayres was not an artist who wished to be part of a group or club, but, as one friend described her, was someone with ‘a waywardness, an idiosyncratic individuality’. It was a trait that manifested itself early on. Arriving as a 16-year-old student at Camberwell School of Art in 1946, she immediately chose to ignore the prevailing dictatorial ‘Euston Road School’ of teaching (what she called the ‘dot and dash and measure’ approach) led by William Coldstream, preferring instead what she saw as the more forward-looking, freer attitude in Victor Pasmore’s Saturday classes.

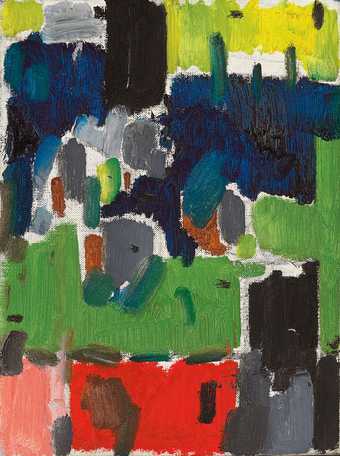

She would be further inspired, not only by Rubens, Turner, Picasso and Matisse, but also by more contemporary figures. A visit to see Tate’s exhibition The New American Painting in 1959, which included works by Willem de Kooning, Sam Francis and Jackson Pollock, encouraged her and would prompt a move to work with her canvases laid on the floor. However, she also acknowledged Roger Hilton as a singular direct influence on her work at that time. She had met him some years earlier and later recounted that it was first time anyone had really talked to her about painting.

While her painting continued, she dedicated herself in the following years to raising her two sons, as well as teaching. From 1959 to 1965 she taught at Corsham School of Art, along with her husband Henry Mundy and fellow friends and artists Howard Hodgkin and Robyn Denny. In 1978 she became the first woman to run an art department in a British Art School, as head of painting at Winchester Art College where she stayed for three years. In the early 1980s her public recognition grew with each exhibition, most notably with the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford in 1981 and the Serpentine Gallery, London in 1983. The eighties saw her move to a more exuberant and colourful palette in what some felt would be the start of her most productive period, one coinciding with a move to a remote house near Llaniestyn, North Wales.

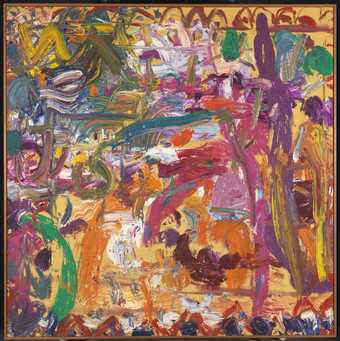

Gillian Ayres CBE RA

Antony and Cleopatra (1982)

Tate

Liberated from teaching, and no doubt moved by the light and space of the Welsh landscape, she changed her methods and style. The canvases got bigger (some over three metres long) and she worked more rapidly, producing numbers of dense and thickly impastoed paintings that signalled a distinct move away from the muted colours and densely worked surfaces of the previous decade. One of these was Antony and Cleopatra, done during the winter of 1981–2 (and now in Tate’s collection), which she explained as aiming for a sense of the sublime through the scale of the markings she made.

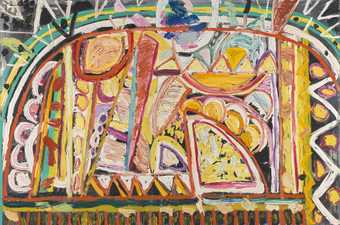

Ayres lived in Wales until 1987, when she moved to a 15th-century cottage at Morwenstow, on the Devon–Cornwall border. Visitors remember a lively house where offers to tea, coffee or champagne were taken amid the bustle of cats, dogs and other animals. Her studio was no less busy, with unstretched canvases draped over chairs in a room described by one visitor as a ‘cheery muddle of paint-spatter, house plants, stepladders, tins of colour and canvases’. Here she continued her large-scale paintings, such as the strident picture Phaëthon from 1990 (also in Tate’s collection) with its triangles, circles, semi-circles, and zig-zagging packed together in shades of orange, yellow, red, white and blue; a picture redolent of a life well-lived, and an artist much admired.

Gillian Ayres CBE RA

Phaëthon (1990)

Tate

A display of Gillian Ayres’s work, curated by Andrew Wilson, Senior Curator of Modern and Contemporary British Art and Archives, is at Tate Britain from 3 June.

Simon Grant is Editor of Tate Etc.