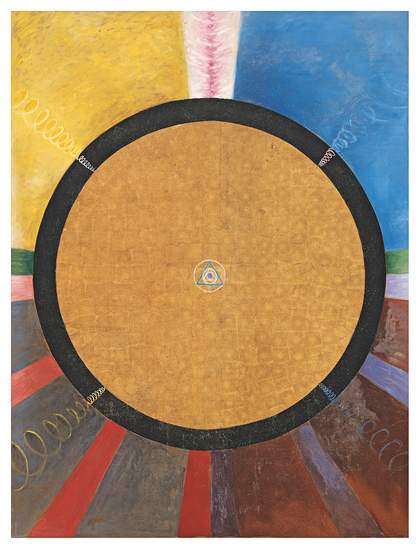

Hilma af Klint, Group X, No.3, Altarpiece 1915, oil paint and metal leaf on canvas, 237.5 x 178.5 cm

Courtesy Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

The months leading up to last year’s presidential election in Brazil brought into focus two distinct changes at work in the country: an increasingly polarised view of the world, and the co-existence of multiple truths.

The political campaigns for both sides made use of simplified ideas of right versus wrong, good versus bad, honest versus corrupt, proper versus immoral. It seemed that concepts of memory, ethics, justice, equality and, consequently, democracy had never been so elastic. Double standards were not taboo either – not even in the highest Federal Courts, where decisions appeared to have been motivated by vanity and greed, rather than impartiality.

Conflicting narratives have, of course, always existed, but what has been most alarming recently is the increasing dissemination of strategic lies, fake news, historical revisionism and manipulated truths. The effect has been an undermining of civil authority, where common sense has been ridiculed and ethical limits eroded. In the blink of an eye, ideas of cross- and multicultural heritage – the essence of Brazilian culture – and a shared forward-looking perspective seem to have been replaced by fundamentally diverging notions of nation-building, amid battles for power and public opinion.

Sadly, similar developments can be observed around the globe, reflecting a painful disassociation between the ways we see, the ways we learn, and how we interpret and value the world we live in.

How do the arts operate in light of this? Historically, the arts have aimed for a language that allows for fiction, that qualifies the unknown and that allows for doubt.

Art muses on the unknown and thrives on inventing signs for phenomena or things we have not yet named. It can do this because it naturally joins thinking with doing, reflection with action. Art is grounded on imagination, and only through imagination will we be able to find new ways into the future, just as pioneering abstract artists such as Wassily Kandinsky, Hilma af Klint and František Kupka believed in the potential for interrelated forms of knowledge – from molecular biology to esotericism – to inform the creation of their new visual language.

Throughout the 20th century, artists have developed many new strategies for the changing times. Think of the Belgian artist Marcel Broodthaers’s 1968 project for a conceptual museum, the Museum of Modern Art, Department of Eagles, a fictive model of an art institution created to point to a political or institutional reality.

We know that the model has become a central instrument in scientific theory, mathematics, and natural and social sciences – something to be used to simulate reality, to question it and understand it. It has also been used in art – from dadaism, surrealism, Fluxus and the Situationist International, up to today – establishing itself as a powerful and most poetic form, and a beautifully subversive tool too.

Over recent decades, many artists have referred to their actions, installations and creations as models – representations they understand as proposals to the audience, ones that need to be activated through the visitors’ participation and interaction. These can be architectural forms demonstrating the potentials of possible social spaces. But they can also be sets of rules or instructions – practical or fantastic – revealing behavioural codes and power structures within such spaces and exemplifying experiments about life through the arts.

If we truly believe in the transformative capacity of art, then we should ask ourselves: how can we apply the idea of a fictional model to our own social and political lives in order to comprehend, experiment with and accept the multiplicity of truths that surround us?

Jochen Volz is General Director of the Pinacoteca de São Paulo, Brazil.